Reading guide of The true Celtic language and the Cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains by Alessandro Lorenzoni* & Mariano Tomatis Antoniono®

* Alessandro Lorenzoni, writer and researcher, collaborates with the Research and Documentation Group of Rennes-le-Chàteau. E-mail address: Lorenzonialessandro@libero.it ® Mariano Tomatis Antoniono, writer and researcher, publishes the website www.renneslechateau.it Web contact: www.marianotomatis.it

You can find the original Italian article HERE. With thanks to Mariano for permissions to translate articles in the interests of research. Translated by Rhedesium. Following the Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International restrictions placed by author[s].

Publication date 2007 - Usage - Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

You are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format & Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. ________________________________________________________________________________________

Although very bizarre, the book The True Celtic Language and the Cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains presents a precise hypothesis: after the Great Flood, one of Noah's grandsons, Gomer, fathered the descendants of the Gauls, maintaining the Primordial Language almost unchanged; after a few centuries, a tribe of Celts settled in the valley of Rennes-les-Bains and a council of wise men, the Neimheid, gave their names to the various rocks in the area and the Druids built two gigantic cromlechs to the glory of the one God. The toponyms of the area (but also many names taken from biblical texts) broken down and interpreted in English - the Primordial Language - allow us to reconstruct the history of the place, the religious traditions and to identify the Celts as the people who anticipated the faith in the God that Christ would have announced only a few centuries later.

***

A few kilometres from Rennes-le-Château, in a clearing surrounded by a thick forest, the Sals stream, also known as the "salty river," springs forth. Within a veritable miniature Arcadia, the stream flows through the gorges of the Coumes mountain range, leaving behind its source, the Fontaine Salée (Salty Spring), located near the small mountain village of Sougraines. This small Alpheus finally joins another stream, the Blanque, near a mysterious town, Rennes-les-Bains.

"I would feel guilty if, among so many strange figures, I did not mention the venerable priest of Rennes"(1): this is how Jean Pierre Jacques Auguste de Labouisse-Rochefort described the curate of Rennes-les-Bains, Jean Cauneille, in 1832. While many doubts and perplexities can be expressed regarding the mystery surrounding Father Jean Cauneille and his works (La ligne de Mire and Le Rayon d’Or [The Line of Sight and The Golden Ray], which have been confirmed as apocryphal and nonexistent, there is another priest from Rennes-les-Bains who, rightly or wrongly, can be described as enigmatic: Father Henri Boudet.

Unlike his predecessor, Father Boudet wrote several works that even today, some 150 years after their publication, are still considered authoritative not only in scholarly historical circles but also in esoteric circles. What is the reason for this fame? According to Father Henri Boudet, in his small parish were the last vestiges of a Druid sanctuary surrounded by a cromlech some twenty kilometres in diameter (which would make it the largest prehistoric sanctuary of antiquity). This place of worship, properly called a Drunemeton, was said to have been one of the most important in all of Gaul and, like the much more famous one in the "Forest of the Carnutes," would have hosted, once a year, a meeting of all the Druids of southern Gaul. Referring to linguistic theories that were far from new, at least for that historical period, the venerable priest of Rennes delved into the exegesis of every proper name of person and place in his region and of the Holy Scriptures, to the point of proving the existence of a language common to all humanity since the time of Adam and that all ancient languages (including the dialects spoken in Normandy, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and southern France) derive precisely from this primordial idiom. This mysterious original and primitive language, according to the reverend, would have been Anglo-Saxon, identifiable as the true Celtic language. In the following chapters, we will delve deeply into his most famous work: the one he dedicated to the enormous cromlech around Rennes-les-Bains and the Celtic language.

The question of dating

The True Celtic Language and the Cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains bears on its title page the date of 1886 and the publisher "Francois Pomiès éditeur - Carcassonne”. The latter, also specialised in religious works, remained in business until 1889, to be replaced by the publisher Bonnafous. Despite this, according to some researchers, the publication date of the book is clearly incorrect (and therefore contains a coded message), as the publisher Francois Pomiès had ceased its activity in 1880. In reality, these considerations are clearly incorrect: Pomiès continued its activity until 1889 (this is proven by several Pastoral Letters of Monsignor Bishop Billard, published in 1888 by Pomiès). In 1889, Pomiès retired from business and was replaced by the publishing house Gabelle, Bonnafous and Cie(2). In 1899, the publisher changed its name again to V. Bonnafous - Thomas.Other researchers have advanced the hypothesis that the book was printed in 1880 (before the alleged bankruptcy of F. Pomiès). This statement is also clearly incorrect, as Boudet quotes throughout the book what was supposedly written in the Melbourne newspaper The Advocate of September 5, 1885(3). This allows us to date the publication to a time certainly after 1885.

The Print Run

The French esotericist Pierre Plantard, in his Preface to the 1978 edition of Boudet's book, claims that the book was printed in 500 copies, for the considerable sum of approximately 5,400 gold francs, of which only 98 were sold. However, no evidence is provided for this estimate, which in any case appears plausible. Boudet most likely managed to print the book thanks to an inheritance or the help of his brother, a notary. Thanks to the Rennes-le-Chàteau affair, Henri Boudet's book became one of the great classics of French occultism, reprinted seven times by as many publishers (Philippe Schrauben, Demeure Philosophale, Pierre Belfond, G. Wendelholm, Bélisane, Lacour-Ollé, and Oeil du Sphinx).

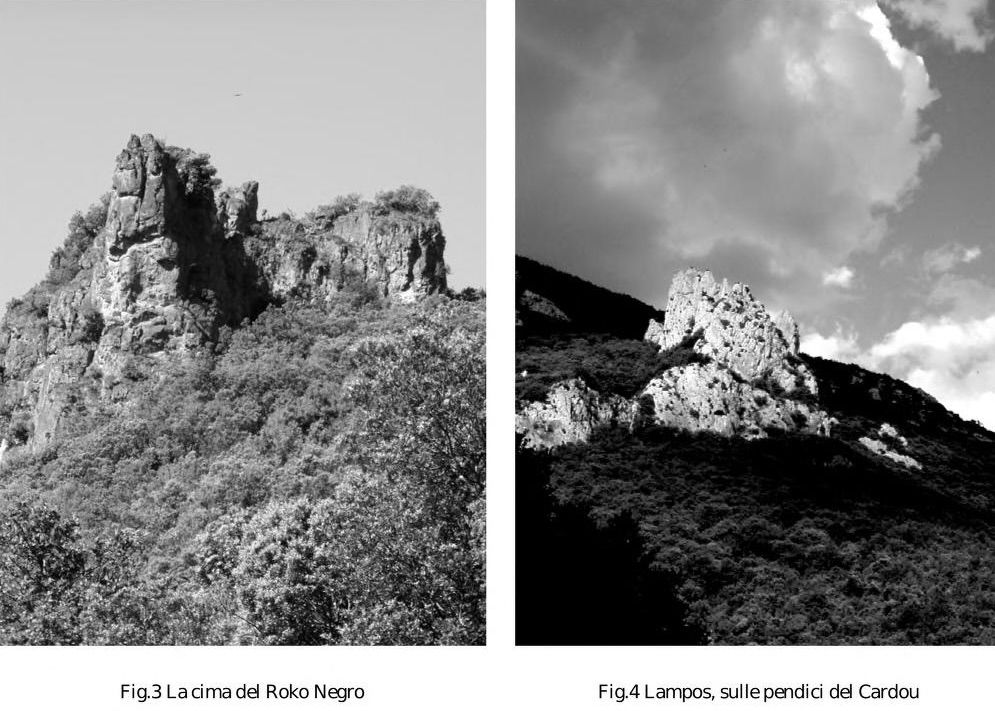

The attached map

At the end of the book is a map of the area around Rennes-les-Bains, entitled Rennes Celtique, created by his brother Edmond. This map is essential for understanding the places the priest refers to throughout the text. This is a representation of the Rennes-les-Bains region, highlighting the Standing Menhirs (identified by a dot), the Fallen Menhirs (identified by a hyphen), a Dolmen (identified by an ideogram similar to an H), and the Incised Crosses (identified by crosses). It should be noted that at the time, surveyors did not yet exist, and notaries had to carry out precise measurements and cadastral maps themselves. We know for certain that two versions of this map exist, and that they were printed in greater numbers than the books.

Text Structure

The text consists of 310 pages plus the Avant Proposal and Preliminary Observations; two additional pages depicting "megalithic" structures have been inserted between pages 244 and 245 of the text. Designed by his brother Edmond and signed "Ed. Boudet," they bear the inscriptions: "1, 2: Roulers of the Pla de la Coste - 3: Menhir knocked down - 4: Menhir erected/Standing stone located opposite the Borde-Neuve on the left bank of the Sals." The book is divided precisely into eight chapters, in addition to the Avant Propos and the Preliminary Observations.

Text Analysis

What follows is an exposition of the results of the research undertaken by Henri Boudet, which in turn is the fruit of historical studies conducted since the sixteenth century on the Celtic people and of bold etymological deductions. However, Boudet's book is not as simple as it may appear, because he is, in some ways, a problematic writer: his work is, in fact, a veritable mosaic of other works carefully chosen to create a coherent text. It brings together currents of thought that have spanned centuries, but his book is also unique in its genre for the theories it presents. To consider the work as a "treasure map" or an esoteric manual seems infinitely reductive: The True Celtic Language and the Cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains is an exoteric work, whose profound message shines through clearly from the lines and is revealed through solid clues. But it is not only this: today, in the light of "consolidated" archaeological knowledge, this book can be read as one of those few "frontier texts," or rather, texts that are settable on and under and on the boundary line that acts as a watershed between pure fantasy and what at the time was considered merely a new science: etymology at the service of the historical reconstruction of the past of places.

Preface

From the preface, the priest informs us that "the Celtic language is not a dead, disappeared language, but a living language, spoken throughout the world by millions of people." This revelation is intended to pique the reader's curiosity, and it also constitutes the culmination of the priest's analysis: not only is this language still alive in modern dialects, but—precisely thanks to this survival—it "helped him discover the magnificent Celtic monument that exists in Rennes-les-Bains." This—so to speak—local discovery is accompanied by another, more far-reaching one: identifying the most ancient origin of names in the Celtic language has led the author "to etymological deductions that seem difficult to refute," deductions that he will apply throughout the text, both geographically and biblically, with curious and improbable results.The alleged cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains is such a significant figure that it can be considered a true symbol of the rebirth of the Celtic language.

Preliminary Remarks

In his preliminary observations, Boudet seems to maintain that his discovery occurred by chance, while he was studying the antiquities present in the spa town. However, analysing the history of Rennes-les-Bains in detail during the time of the Celts has proven difficult due to the lack of written documents. The priest therefore draws inspiration from a sentence that Count Joseph de Mâîstre wrote in the "Seuxième entretien" of the book Les Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg, ou Entretiens sur le gouvernement temporel de la Providence: "The dialects, the proper names of men and places seem to me to be almost untouched mines, from which it is possible to extract great historical and philosophical riches.” The priest's starting point is the Occitan dialect; this dialect is thought to derive from an idiom spoken by the population who, in ancient times, occupied the region. Boudet identifies this people as the Volci Tectosagi, whom Caesar mentions in De Bello Gallico (Book VI, 24), whose language is not only the origin of Occitan but also seems to have influenced Hebrew, Basque, Punic, and Celtic. Two "Shaking Stones," which Boudet considers to be megalithic monuments built by the Gauls, invite the astute observer to ponder a "very dark past," or rather, the profound meaning that drove their mysterious builders to erect them. The past is revealed to be dark precisely because of the lack of written texts, and the only fire that can dispel the darkness is represented by that mysterious primordial language spoken by the Volci. But how can this language dispel the darkness? Boudet reveals this in the next chapter, entitled "The Celtic Language.”

Chapter I - Celtic Language

Boudet prefaces his observations on the true subject of the chapter—the Celtic language and its interpretation—with a brief historical excursus on the Gaulish nation and its origins. In this regard, the Reverend cites historian Henri Martin's book, Histoire de France, and in particular a sixteenth-century tradition according to which the Gauls descended from Gomer, the eldest son of Japheth and therefore grandson of Noah. This belief was cited by a wide variety of authors, from Chateaubriand in his Mémoires d'Outretombe to Father Grégoire de Rostreren in his Dictionnaire francais-breton. Reverend Father P. Pezron was no exception, in his monumental work Antiquité de la nation et de la Iangue des celtes, autrement appellez gaulois (1703), devoted an entire chapter to this theory. Boudet was no exception, as we will see in the next chapter. This belief should not be surprising: as a true follower of the theory of creationism, Boudet believed that after the Great Flood, Noah's three sons—Japheth, Shem, and Ham—had fathered all the peoples of the earth. The Gauls would therefore have been the first people after the Flood to inhabit the French nation. Indeed, Boudet writes: "The Gauls, descended from Gomer, son of Japheth, left Asia Minor at an unspecified time, spread throughout Gaul, pushing the Iberians southward, the Ligurians eastward, and invading Spain, mixed with the Iberians." Reconstructing the original language was therefore equivalent to going back to this recent past.

Henri Boudet then addresses the issue of the descent of the Gauls. According to the priest, Gaul was inhabited first by the Gauls, then by the Cimri, and finally by the Belgae; from the Belgae descended the Volci Tectosagi and the Volci Arecomici. After questioning the origin of the name Celtae (derived from Kell, which, according to a certain Father Bouisset, author of a Mémoire sur les trois collegés druidiques de Lacaune in 1881, meant a mature man), Boudet asks why, according to Caesar (Book I, 1), the numerous Celtic tribes spoke different languages. The priest of Rennes-les-Bains concludes by asserting that the tribes did not speak different languages, but different dialects. This is a very important step, because the Celts are recognised as having a linguistic unity. The true history, however, would not be contained in Caesar's memoirs, but would be "engraved in the soil" that the Celts occupied: "They gave the tribes, the lands, the mountains, the rivers of Gaul names that not even time could erase. Their true history is contained there. These names certainly have a precise meaning, full of interesting revelations, although all languages seem ineffective in solving such enigmas.”

The attempt to reveal the meaning of the terms that defined places and people was carried out by breaking them down into parts and seeking a series of meanings that would fit those realities. Naturally, it was necessary to discover which language would be best suited to "open" the lock that would reveal the hidden meanings. The problem had long been open; As Boudet writes, "the deconstruction of these proper names of places, men, and tribes has seriously interested a good number of thinkers: we have endeavoured to research this language that has filled our soil with indelible names, whose obscure meanings pose an incessant challenge to our legitimate curiosity.”

This is a crucial passage in the book: as we will see, it is precisely the cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains, with its standing stones, its fountains, its streams, and its mountains, that will lift the veil of mystery that, according to Boudet, shrouds the history of the Celtic people.

The Reverend writes further: "Sir William Jones, founder of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta, had first noticed a certain affinity between Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. They must therefore have a common origin, and, without daring to affirm it, he suspected that Celtic and Gothic came from the same root as Sanskrit. Françoise Bopp's Comparative Grammar of European Languages then explained how grammatical laws allow us to discover between Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, and Gothic, no longer a simple affinity, but a real community of origin.” Boudet concludes that it was thought that "the Sanskrit language could perhaps provide the key to the Celtic language, and this was all the more believed given the fact that the Celts arrived from Asia, the cradle of the human race." However, since Celtic terms have remained almost unchanged in many of the languages still spoken today in France, Ireland, and Scotland, it is sufficient to use the more modern "Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Breton, and Languedocian dialects," which show significant overlap with the ancient Celtic language. To prove his point, Boudet cites some very similar terms in the various languages; for example, "the film of ground and sieved grain is called, in the Languedocian dialect, brén; in Breton, bren; in Welsh, bran; in Irish and Scottish, bran.” At this point, the attentive reader might ask a more than legitimate question: why is the key to the true Celtic language Occitan and not Breton, a language that has always been considered the closest there is to Celtic?

Boudet takes this obvious objection seriously, writing: "It must seem bizarre that the Languedocian dialect was chosen rather than Breton to begin the journey; we will invoke a serious historical reason for this, and by closely examining the migrations of the Volci Tectosagi, we will be fully convinced of the correctness of this choice.”

Caesar mentions the Tectosagi only once, placing them in Germany on the right bank of the Rhine, and then mentions them no more. The priest then cites the opinion of some historians according to which in the "4th century BC, two tribes said to belong to the Belgae, the Volci Tectosagi and the Volci Arecomici, crossed Gaul and came to settle in the Gallic South (Midi Gaulois) between the Garonne, the Pyrenees, and the Rhone." The fact that the Volci Tectosagi were dedicated to conquest and plunder does not derive from archaeological finds or studies of the territory, but from purely "etymological" considerations: Boudet in fact applies his technique of breaking down nouns to the words "Volci Tectosagi" for the first time and, taking a somewhat excessive liberty, writes: "Volkes (Volcae) derives from the verbs to vault (vàult), to vault, to make leaps and to cow (kaou), to intimidate; Tectosagi is produced by two other verbs, to take to (téke to), to take pleasure in..., and to sack, to pillage, to plunder. Bringing together the four verbs that make up the two appellations, we note, in their distinct meanings, that the Volci Tectosagi frightened their enemies with the speed of their manoeuvres in combat and loved to devastate and plunder." This interpretation (like those that will follow throughout the book) is totally wrong; As Jacopo Garzonio wrote more recently: "The name Tectosages is a bimember [Rhedesium Editor - bimember refers to something composed of two distinct components or members] compound: [...] sagè is a verbal root that, without a doubt, is the same as that underlying the Old Irish saigid 'searches, sets out in search of' and the Latin sagire. As for tecto-, it was traditionally compared with the Old Irish techt, the verbal noun of tiag- 'to go, advance, depart', and the Welsh taith 'journey', so the meaning of Tectosages (or rather, its descriptive value) should have been 'those who seek wandering, those eager for wandering'. Today, tecto- is preferred to be considered in relation to the Old Irish verb techtaid 'has, possesses' (also as a legal term: 'legally possesses'), whose verbal noun techtad has an abbreviated form techt 'possession, property'. Following this path, the meaning of Tectosages is 'those who are in search of possessions, of property'"(4).

According to Boudet, the Volcae Tectosages - who had occupied the Pyrenean area - were the custodians of the true Celtic language: being, according to historians, of Cimbric race, they belonged to the Celtic family, and "therefore, Cimbri and Tectosages had to speak the language of their family. The possession of the island of Brittany by the Tectosages exercised on them a favourable influence for the conservation of their language and their customs. Isolation preserved them from the profound alterations undergone by the languages of other peoples of Europe, while leaving them maximum freedom for distant colonisation's, which are a typical trait of their character".

To complete what he believes to be the "proof" that the Languedocian dialect has its roots in the Celtic language, Boudet presents a long list of terms in the two languages, underlining the many similarities. Aware of the historical weakness of the scenario presented in the previous paragraph, the reverend writes: "The genealogy of the Anglo-Saxons, as we present it, might still, despite everything, seem purely hypothetical to some, but it is easy to support it with convincing evidence, since the language of the Tectosages has left deep traces in Langudocian idiom'". Something that is scattered is spatarrad, in the Languedocian dialect, and the English verb to spatter expresses the concept of scattering(5); the Languedocian Spillo and the English spill both indicate a splinter of wood, etc. For clarity, Boudet cites two works from which the terms were extracted: Percy Sadler's English-French Dictionary and English grammar by William O'Farrel, "for its order and clarity." In the final paragraph of the chapter, Boudet argues that the identification of the Celtic language with that of the Tectosages becomes even more plausible by breaking down the names of the different Gaulish tribes and the land they occupied. Among the many examples the priest offers, one is significant: "Why is the city of Rennes in Brittany and the spa town of Rennes-les-Bains in the department of the Aude regions bearing the same name? It is evidently because of the similarity between the two countries in their menhirs and their wobbly stones'. This consideration is the fruit of Boudet's imagination rather than a precise historical-etymological investigation, but since it is functional and at the same time consistent with his basic thesis, it is presented as established ("evidently..."). Boudet therefore goes a step further: is the fact that such distant places have the same name not proof that in ancient times there existed a group of wise men, a clearly constituted body of scholars charged with giving names to each city and to all parts of the Celtic soil? He writes: "These names, which cover the entire Celtic territory, are certainly not the work of the people; the conscientious, exact, and faithful composition of these very important names could not be left to senseless and unfounded whims. There was certainly a body of wise men charged with this task; and what makes this clear are the similar names attributed to countries located at the first and second ends of Gaul."

The priest manages to give a name to this body of scholars through one of the first extrapolations and linguistic fantasies that characterise the entire book. First, the note that Henri Martin inserts on the first page of his book Histoire de France is transcribed: "According to Irish traditions, Gadhel or Gaèl, personification of the race, is the son of Neimheidh. But who is this Neimheidh, this mysterious figure who hovers over our origins? History cannot answer."

History cannot answer, but Boudet believes he can do so by breaking down the term Neimheidh using the usual technique: "Neimheidh is not the name of a Gallic chief; It means he who is at the head, who commands, directs, and gives names, to name (nòne), to call, to name to head (hèd), to be at the head, to lead, and it was physically impossible for a single man to give the entire Celtic nation the names that cities, tribes, rivers, and even the smallest parts of territory have: it was therefore the work of a college of sages, and the term Neimheidh, applied to this body of scholars composed of Druids, represents an expression of undeniable clarity, since the Druids were at the same time priests, judges, undisputed leaders of the Gauls, and charged with the transmission of all sciences'.

Therefore, the Neimheidh would be, in Boudet's fantasies, the council of sages that "gave names" to cities, tribes, and territories.

Chapter 1 - Hebrew Language

In this second chapter, the author takes up the tradition that Gomer, because he is the father of the Celtic nation, tries to show that through the Celtic language, henceforth called "Anglo-Saxon," is closely related to the Hebrew language. To do so, the curate applies his technique of decomposition to each name in the Old Testament, demonstrating that English is capable of revealing details about the person it refers to: "Assuming that the language of the Tectosagi is the true Celtic language, it seems evident that the purest expressions of this language are found abundantly in the names of the leaders of this family, whose expansion has almost covered the world. The paternity of the Celtic and Cimbrian nations is traced back to Gomer, eldest son of Japheth; therefore, there should be in the Anglo-Saxon language, which we will henceforth call the Celtic language, a great similarity with Hebrew, and a certain conformity in the monosyllabic terms of the two languages, at least for most of the words that compose proper names, if not for the entire language. This thought is too solidly founded for us not to examine whether the Celtic language can explain the names of the first men cited in the books of Moses, and also in some other books of the Hebrews'.

It would be pointless to repeat many examples given by the priest; we can limit ourselves to the one relating to the name of God:

"Elohim is the name by which men first designated the Lord who created the earth and deigned to bless it, dedicating it to his glory. The Hebrew expression Elohim, the rabbis say, is placed in the plural out of respect for God, because in the singular it would be Eloha. The Jews derive it from el, strong and powerful, and from ala, to compel, to subjugate (astreindre), because God compels and subjugates himself, so to speak, to use his power for the preservation of created things. If we may speak frankly, we would say that the Celtic language explains the meaning of Elohim much better. When God created man and woman in his image and therefore capable of blessedness, of supernatural knowledge and love, blesses them saying: 'Be fruitful and multiply and populate the earth.' It is therefore the multiplication of the human race that God wanted to bless, and the terms "EIohimi" in the Celtic language say nothing else. "Hallow, heam," - "heam" (him) represents the child not yet born, while the verb "to hallow" (hallo) means to bless, to sanctify.

We can only imagine the priest's naive surprise when, for the first time, he thought he had found in English the key to revealing the true meaning of biblical names, and in this passage he expresses it with ill-concealed pride ("If we may speak frankly..."). To orient oneself in Boudet's translation of the Bible, one can refer to the Bible de Carrières, which according to the priest is "exact and highly regarded.”

Boudet continues to apply the technique of etymological decomposition with the names of the first men: from Adam and Eve, through Cain and Abel, to Noah and his sons. It is at this point that Boudet expresses his conception of the birth of the first races. Boudet traces the story of Noah and his sons and their sons' children, up to the episode of the Tower of Babel, and beyond. After the flood, according to the Holy Scriptures, Noah's three sons, Japheth, Shem, and Ham, fathered all the "races" (this is the term used by Boudet) of men present on earth. The scholar Cuvier identified three varieties of man: the White or Caucasian, the Yellow or Mongolian, and the Black or Ethiopian. According to Henri Boudet, the white variety of Japheth (from "eye" and "fade") spread throughout Europe, Central Asia, India, and Africa; the black variety spread throughout most of Africa and some islands in Oceania; and the yellow variety spread across the Tibetan plateau and Great Tartary. Japheth's was "the royal and incontestable stock" of the whitest human race. The sons of Shem, of whom the best preserved type is described in the Arabic, have a more or less tanned complexion, but the distinctive feature of the first family is shown in their black eyes and hair. This, however, can only be a general characteristic; and, among the Jews, direct descendants of Shem, Sacred Scripture records an exception in the person of David, whose hair was red.

After the flood, men had multiplied beyond measure, but all spoke the same language. It was after the episode of the Tower of Babel that, according to the priest, many different languages arose. This is a crucial point in Boudet's analysis, which must demonstrate how the primitive language remained intact even during the Babel confusion. The priest therefore asks: "Did the primitive language disappear in this confusion? We can say, with certainty, that it remained in use in the mouths of some of the sons of Shem and also of some of the sons of Japheth; And this primitive language is like the starting point of the other languages spoken in the world, like a spring that gives rise to countless streams that then meander in the distance. This language was perpetuated perfectly among the Jews until the sojourn of God's people in Chaldea significantly modified it. Did Gomer's descendants pass it on intact, at least in its essential parts? We will try to demonstrate how the integrity of the primitive language was preserved in the family of Japheth more securely than in the family of Shem, perhaps because of the universal dominion promised by God to Japheth's descendants. In the following paragraphs, Henri Boudet interprets the names of Abraham, Lot, and the Patriarchs, obtaining very curious and bizarre results. The term Sodom, for example, is broken down into sod - ground and to doom - to judge, condemn. The story of Moses and the Hebrews in the desert follows. Here too, Boudet cites some interpretations of geographical terms: he "translates" Mount Sinai into -to shine - to shine, to sparkle, to re-spend, and to eye - to look upon, to have one's eye upon. The chapter concludes with a paragraph dedicated to David, Goliath, Joshua, and the Saviour. Jesus is interpreted using the Hebrew term issa and becomes 'to ease - to liberate and to sway - to govern, to command'. "These examples," Boudet concludes "seem to us sufficient to offer solid support to the assertion that the Celtic language is in fact the original language, and we will not pursue this initial etymological study of Shem's lineage any further.”

Chapter III - Punic Language

In the next chapter, Boudet revisits the theory of Noah's lineage, and in particular that of Ham and his son Phut. According to the priest, it was from this latter biblical figure that the lineage from which the North African population originated originated. To describe the name Misraïm—brother of Phut—the author inserts a curious passage into the text, relating to labyrinths:

"Mesraïm is famous as the first king of Egypt: nevertheless, he deserves to be noted in other ways for the architectural genius he handed down to future centuries, whose creator, in their ingratitude, they have forgotten. The ancients had built certain monuments called labyrinths in various regions, and the most famous were the one in Crete attributed to Daedalus, and the one in Egypt, whose wise architect remained unknown. Herodotus considers the Egyptian labyrinth the work of twelve kings, while Pliny believes that only Tithoïs should claim the glory. According to Herodotus's description of this building, twelve palaces were enclosed within a single wall. One hundred and fifteen apartments, including terraces, were arranged around twelve main rooms, and the corridors were structured in such a way that those who entered the palace were unable to find their way out. There were still one hundred and fifteen underground apartments. Was this construction a monument dedicated to the sun, as Pliny seems to believe, or was it intended for the burial of kings? Was this not rather a whim, a fantasy of a skilled architect, forgotten by men? Mesraì'm alone can put us on the right path and show us the way out of this labyrinth of hypotheses, revealing that he himself is the architect of this strange building, composed of long rows of apartments, and the result of a fantasy, a whim of his ingenuity. Maze (méze), labyrinth, or to maze (méze) to bewilder, to stun - row, (rò), row, line, - whim (houim), whim, fantasy.

A brief historical excursus follows regarding the Numidian kings, the empire of Carthage, Libya, and the Kabyil language. In this regard, Boudet introduces the concept of the Punic language: "The Phoenicians, founders of Carthage, spoke the Canaanite language, and this language, despite numerous differences, must have demonstrated a close relationship with that of the Numidians. But is it really to the language of the Carthaginians that we must attribute the name Punic (punìque), or does this appellation, rather, not refer to that of the Numidians and the Moors? We believe that the Numidian language can easily claim it, and a close examination of the current language of the Kabyls will confirm that it is made up of puns and therefore truly Punic—to pun (peun), to make puns.”

But Boudet doesn't just cite the Bible or history books to explain who the Numidians were and from whom they descended: he also brings in Greek mythology, and in particular the myth of Erad, a symbol of power and strength linked for centuries to the Gauls. Ultimately, even the spoken language of the North African peoples (the Punic language of the Carthaginians and the Kabyle spoken by the Kabyli, undisputed descendants of the Numidians), in addition to being of Celtic origin, clearly derives from the language that preceded Babel, as the Celts arrived in Africa, where they mixed with the population. Boudet concludes: "The examples cited are sufficiently numerous to demonstrate a clear derivation of the Punic language from the language that preceded Babel.”

Chapter IV - Family of Japheth

The fourth chapter, one of the longest, describes the lineage of Gomer, citing Saint Jerome and Josephus. Gomer had three sons: Askemz, Riphath, and Thogorma. The descendants of Askemz settled in cold Northern Europe, the sons of Riphath on the southern coast of the Euxine (the Black Sea), and the descendants of Thogorma occupied Phrygia.

The character who most interests Boudet is Gomer's brother, Tubai. He had moved with his tribe, called Tobelians or Iberians, to the Caucasus Mountains, between the Black and Caspian Seas. According to Basque traditions, part of this tribe, under the leadership of Tharsis, set sail for new lands to occupy; and they found a vast expanse of land, what is now the Iberian Peninsula. Thus, the Iberian language, the same one spoken by Japheth, would have been preserved by the Basques in their beloved Pyrenees mountains. This daring tour serves Boudet to reconnect his land to the descendants of Noah, thus establishing a direct connection between the peoples who spoke the original language and the Languedocian dialect.

To prove that the Basque language derives from the Celtic language, the priest adopts the same procedure already used with Hebrew, Occitan, and Punic: he breaks down some nouns from the relevant language (in this case, Basque) to interpret them phonetically using English. The most curious result concerns the twelve months. "Urtharrilla," for example, which defines the month of January, is said to derive from the bad weather that stops the work of those who would harrow their fields: to hurt, to harm, to harrow, to harrow, etowill, to desire. Taken out of its context, the list of the twelve months has acquired an important role within the text because it has been interpreted as a treasure map, a map that is absolutely vague and varies in different authors. Here's an example:

"Sunrise: a man exhausted by fatigue. Morning: walking easily. Evening: running quickly home. A field. A spring: starting to run quickly. A fountain: rushing. Hut: a crowd of heads under one roof; killing the disgusting insects that sting with a pin. House: meditating. Cellar: part of the house where one can be stupefied by drinking. Thunder: seeing the lightning above that is sure to strike. Darkness: calming the murmurs. The eye closes as if under the effect of a blow. Crying. Refusing the necessary. Breaking a leg. Uttering cries of horror. Looting. Being forced to have white hair. Paying close attention to instructions: speaking a certain jargon for the outside world."

Boudet then describes the habits of the Basques and the practice of using caves as temporary shelters. To prove this curious custom, the author cites a very famous French historian, Louis Figuier, who first mentioned Cro-Magnon man in his 1883 book, L'homme primitif. Both the priest of Rennes-les-Bains and the historian mistakenly believed that the remains of Cro-Magnon man were the mortal remains of a Basque. Then follows the histories of the Gascons, the Aquitanians, and the Occitans, all tribes of Basque or Iberian origin.

Chapter V - Celtic Language

Boudet openly disputes the claim that the Breton language is the original Celtic language: he admits "that the Bretons have preserved a very large number of Gaulish expressions: this is indisputable; but they have not preserved this language in its purity, and one need only look at their pronouns to appreciate the profound alteration of their language.” After having demonstrated once again that the language of the Tectosages, Anglo-Saxon, is able to explain the names of the Breton language better than any other language, Boudet opens one of the most enigmatic passages of the entire book. The enigma is not posed by a difficult-to-interpret passage or an incomprehensible term, but by the priest's own imagination, which pushed him to invent a new function for the megaliths:

"Carnac [is] famous for its alignments. The standing stones are arranged in long, regular rows and form avenues whose width varies between four and eight meters. A distance of seven, eight, and ten meters runs between each of the standing stones. The central avenues are wider than the lateral avenues, and at one end one sees a large open space, similar to a public square. For a long time, attempts have been made to give a meaning to these alignments formed by standing stones and several kilometres long. If we were allowed to hazard an opinion on these alignments, we would be led to see not a religious monument, but rather a gymnasium, where the Gauls trained to skillfully drive, among multiple obstacles, their war chariots, equipped with fictitious weapons, their cobhains, - kob, horse, - to hem, to gird, and one knows which one. The Celts displayed fearsome skill.

The Carnac complex, therefore, would have been a place where warriors trained with chariots! This entirely fanciful hypothesis is followed by another equally bizarre one, concerning what he believes to be the true meaning of the megaliths. In the paragraph entitled "The Redones - The Celtic Monuments - The Druids - The Carnutes," Boudet cites Figuier's work regarding the meaning of the megaliths and their classification. Figuier simply cites indisputable archaeological findings still used today, according to which dolmens were prehistoric tombs (not Celtic or Gaulish) and menhirs were funerary and religious monuments. Completely contradicting Figuier's opinion, the priest candidly informs the reader that "the opinion of modern science regarding dolmens differs strangely from the ideas aroused by the interpretation of the names borne by the large stones." The etymological breakdown would therefore allow us to identify a new, unprecedented role for the great megalithic monuments. And it was the Redones who hid this meaning in the names of the monuments: "The Redones formed the religious, wise tribe, who possessed the secret of erecting the megalithic monuments scattered throughout Gaul; they were the tribe of the wise stones, read (red) - wise and hone cut stone. Study and science were indispensable to understanding the purpose of erecting the megaliths, and only they possessed the ingenuity and meaning, having learned them from the mouths of the Druids themselves."

Believing that the Celts - and in particular the Redoni tribe - were the first people to settle in the Rennes-les-Bains area, Boudet rejects the hypothesis that menhirs and dolmens belong to a previous period and instead provides a completely new interpretation:

"The menhir, due to its sharp and pointed shape, represented the basic food, wheat, main (mén) - main, ear (ir) - ear of wheat. How strange! In all our villages in the Languedoc there is always a piece of land associated with the name of Kaì'rolo, key - key, ear (ir) - ear of wheat, hole - field house. In this field, the grain store of the Celtic villages was probably built. The distribution of wheat was carried out by the Druids, as several authors have clearly noted and as is clearly demonstrated by the expression associated with the dolmen which was, moreover, built as a distribution table, to dole- to divide, distribute, and main (mén) - essential, principal. [...] The stone circle, usually round in shape, represents bread: Cromlech, in fact, derives from Krum (Kreum), breadcrumbs, and from to like (laì'ke), to love, to please. In the Cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains, one sees imposing round stones, representing loaves of bread, placed atop enormous rocks. The wobbly stones(branlantes) are called roulers by the Bretons, ruler (rouleur), governor. They are the sign of the divine druidic powers.

The "gastronomic" interpretation of megalithic monuments—which would therefore refer to bread and the distribution of food—is one of the most incredible oddities in Boudet's book, but it is not an end in itself: the priest wants, in fact, to dispel the suspicion raised by Caesar—that these monuments served as macabre altars for human sacrifice—from the Celts: "The interpretation of the names of all Celtic standing stones, an easy and clear interpretation thanks to the language of the Tectosages, has made these megaliths lose the hateful character that was attributed to them, and places them in a class of very simple monuments, yet having a splendid religious significance.”

By significantly stretching the terms of the question, Boudet is laying the foundations for the conclusion of his text: bread would, in fact, have been considered sacred well before Christ chose it as the "means" of remaining among men during the Eucharist. This concept will be expressed in the final chapter of the book. After proposing a fanciful interpretation of the name "Druids," the priest concludes the chapter with a series of interpretations of place names and personal names in the South of France. A name as long as Vercingetorix is broken down into five English words: war, king, to head, to owe, and risk. Finally, as if to justify the previous one hundred and eighty pages, Boudet concludes by contesting the hypothesis that the Celts were a rude and barbaric people. To these accusations, the council of wise men, "the Neimheid," responds with the religious names and industrial appellations imposed on cities, tribes, and the smallest villages, whose names reveal many surprising things. We must therefore set aside all these hypotheses of cruelty and a barbarous state, outrageous to our Gallic ancestors, and justly recognise the high level of religious, moral, and material civilisation to which they have an indisputable right."

As Mario Iannaccone wrote, "Boudet is evidently interested in redeeming the Celts from the accusation of being ignorant and bloodthirsty savages. [...] Boudet's arguments are particularly clear where he provides his reader with evidence to identify the Celts as a people enlightened by grace, endowed with the wisdom of the prophets of Israel. Boudet starts first from the criticism of the Romans, polytheists who slandered the Celts, failing to understand the prefiguration of redemption that their doctrines supposedly taught. His arrows are directed above all against the hated Caesar, always a figure little loved by French nationalists, for completely obvious reasons (and even caricatured in Goscinny and Uderzo's Obelix)”(6).

Chapter VI The Volcae Tectosages and Languedoc

The sixth chapter does not deal with linguistics, but with history. Henri Boudet describes, skipping several significant details, the different peoples who settled in the South of France and their dominions. The first are the Volcae Tectosages, who would have settled in the region between the Rhone and Béziers, with Nimes as their main city. But the seat of their domination was Toulouse, the largest and most notable city of Southern Gaul. Later, the region they populated would be called Languedoc. The author then addresses the Gothic people, with the distinction between Visigoths (who settled in Spain and in today's Languedoc) and Ostrogoths. (settled in Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the exile of Romulus Augustulus). Then comes the Frankish people, whose name the priest interprets bizarrely, after reading a poem by a Latin author reported by the historian Emile Lefranc in his book Histoire de France:

"The Franks formed a confederation of tribes on the right bank of the Rhine, merging into a generalised name that was for them a sign of cohesion. They prided themselves on a generous and sincere character, frank - sincere, and had renounced the ancient title of plunderers, retained only in one of their first and first tribes.

Boudet recalls that the Franks also held the same beliefs as the Tectosages and the Celts; confirming his skepticism about the opinion of those who maintained that human sacrifices were celebrated at the time, he writes:

"The outward appearance of the Franks did not differ from the outward appearance of the Gauls; their religion bore a striking resemblance to Druidism: it was founded on the immortality of the soul, and, historians say, their altars were never stained with human blood. This last trait of their customs informs us that at the time of the migration of the Tectosages of Toulouse, human sacrifices were not practiced in Gaul. Above all, the Franks' war tactics indicate that they belonged to the true lineage of the Volcae Tectosages and Arecomici."

A paragraph follows dedicated to the first Frankish kings, which breaks down the names of the first Merovingian kings: Merovech, Childeric, Clovis, and Cicero. Curiously, the author indulges in a digression in which he claims that even the Latin language is of Celtic origin:

"Latin itself, taken separately, reveals a certain Celtic character that is surprising at first, but which is easily recognised, since the Gauls were already masters of much of Italy when, 753 BC, Rome was founded by Romulus, the man with the bizarre cloak, rum (reum) - bizarre, hull - external covering."

The last two paragraphs open and close with further digressions concerning the Iberians, the Illiberians, the Caucoliberians, the Sardanians, the mythology of Heracles, and the Atacinians. The central point of his thesis is that the Celts and the Iberians merged peacefully. The Atacini, however, were so named because the Aude River was once called Atax. Boudet's curious attribution to the Atacini is that they were capable of crafting excellent swords and axes. After analysing—using the usual technique of decomposition—the names of the various villages of the Aude (Quillan from killow-hone (black earth and stone), Espéraza or Sperazanus from spar (beam), axe (axe), hand (hand), Couiza or Kousanus from kove (small bay), sand (sand), Carcassonne from cark (care, concern), axe (axe), to own (to possess), the author of Vi de Atacini in to add (to add) eaxe (axe). In this case, too, the ability to craft weapons derives, according to Boudet, exclusively from an etymological consideration.

Chapter VII Cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains

The seventh chapter is entirely dedicated to what Boudet calls the "principal object" of his research: the cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains. The choice of the town's name is said to be due to the fact that "its mountains, crowned with rocks, form an immense cromlech sixteen or eight kilometres in circumference." This cromlech was called a Drunemeton, and the historian Strabo confirms that it was a Celtic custom:

"Strabo, in his history of the Galatians or Asiatic Tectosages, reports that the Gaulish people always had a drunemeton or central cromlech. It was the place where the members of the college of scholars known as Neimheid gathered."

Many have argued that, according to Henri Boudet, Rennes-les-Bains was the only omphalos in France. In reality, this theory could be contradicted by the priest's own words: the cromlech of the Midi was literally the second "navel" of France; the priest first mentions "the northern drunemeton among the Redones of Armorica, which served a large part of Gaul for the work of the illustrious assembly.

However, another central drunemeton or cromlech was needed in the south; it was certainly impossible for members of the Neimheid dispersed throughout the Celtic-Bérican region to reunite with the other members in northern Gaul, and this physical impossibility may have prompted the idea of building a second drunemeton at the foot of the Pyrenees, on the heights of the Val d'Isere, which thus became, in effect, the Redones’."

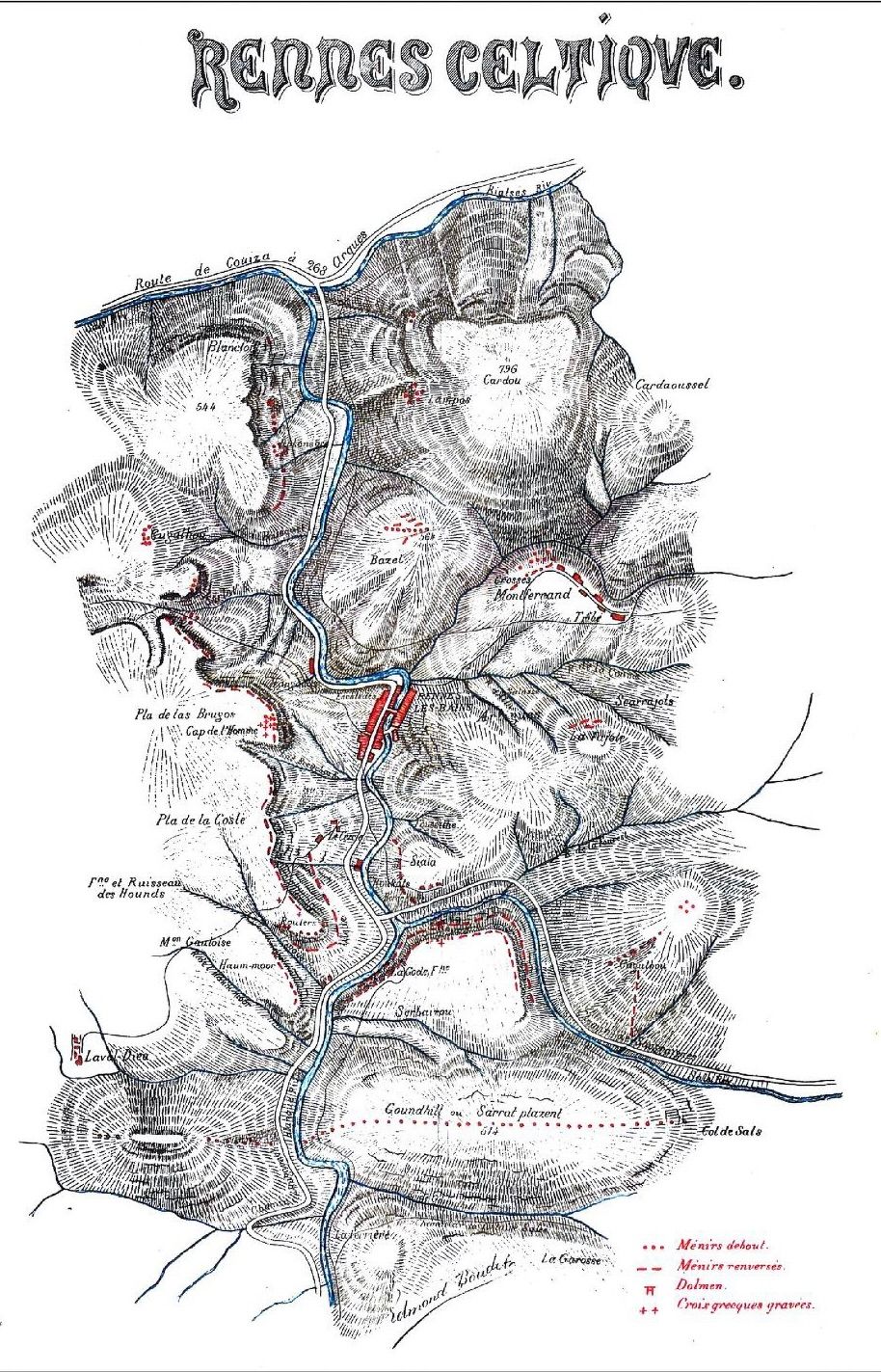

Boudet places the entrance to the cromlech to the north, at the confluence of the Sals and Rialses. Describing the various rocks that make up the cromlech in a clockwise direction, the first notable point is Mount Cardou:

"At the entrance to the Cromlech, on the right bank of the Sals, a mountain called Cardou appears: around the summit, natural peaks begin to rise, known locally as Roko fourkado."

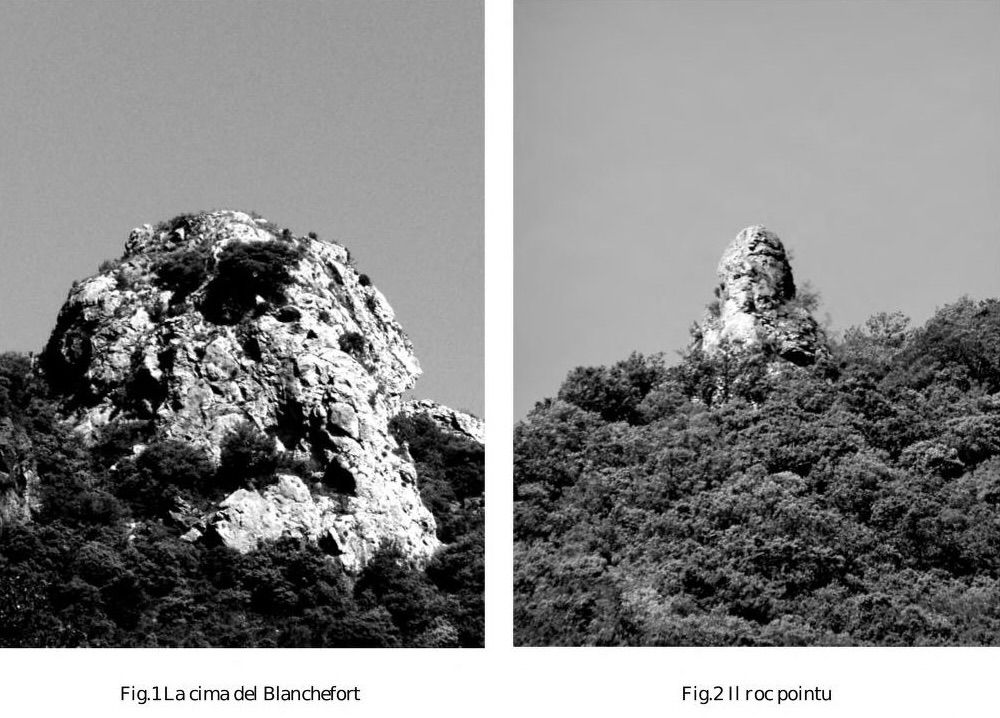

From Cardou, one reaches the lower hill of Bazel, where—according to the priest—there are as many as "three or four hundred [large stones] arranged in order on the crest or lying haphazardly on the slope facing south.” The priest's attention shifts to the other side of the valley, to the west, where "the cromlech begins at the Blancfort rock. The natural tip of this rock was leveled in the Middle Ages to allow the construction of a small fort as an observation point. Some masonry remains (vestiges of masonry) that testify to the existence of this small fort. This white rock, which suddenly catches the eye, is followed by a layer of blackish rocks, which extends to Roko Négro. This peculiarity has given this white rock, placed on top of black rocks, the name Blancfort, blank - white, forth - at the head, above, ahead."

Between Blancfort and Roko Negro stands the Roc Pointu - a spur that Boudet considers an isolated menhir. To the east of Roc Pointu, on one side of Cardou, another "natural rock [...] crowned by several very sharp pinnacles" emerges: the reverend calls it Lampos. On the western side of the cromlech, the megaliths continue beyond the Roko Negro toward a group of rocks known as Cugulhou.

On each of these rocks, the priest tries, on the slopes of the Cardou, to identify traces of human intervention, which he invariably astutely attributes to the Celts. This technique is very lax, since several structures are natural and some carvings, especially those in the shape of a cross, are more likely to be attributed to the custom (much more recent than the Celtic era) of marking the boundaries of agricultural or wooded lands.

Boudet is aware of this possibility, but completely rules it out:

"The villagers are convinced, which is false, that the Greek crosses carved on the rocks represent demarcation points."

A cross of imitation between the municipalities of Rennes-les-Bains and Coustaussa is, however, located in a location well known to the priest. Along a ridge, a series of other rocks reach and cross the Carlat stream, rising towards a rocky summit called Cap de l'Hommé.

"A menhir was preserved in this place, and at the top, carved in relief, was a magnificent head of the Lord Jesus, the Saviour of humanity. This sculpture, which has survived almost eighteen centuries, has given this part of the plateau the name of Cap de l'Hommé (the head of the Man) of man par excellence, filius hominis. It is regrettable that in December 1884, this beautiful sculpture was forced to be removed from its original location, to protect it from the ravages of the pickaxe of a wretched young man who was far from suspecting its meaning and value.

It is doubtful whether it is the same sculpted head that was placed on a wall of the presbytery for several years, from where it was removed in 1992 after a severe flood.

Passed towards the stream of las Breychos, the cromlech would run alongside the Pic de la Coste and reach a group of loose stones called roulers. Today the rocks are stable, but at the time it was possible to shake them vigorously and make them vibrate; the game would still entertain the hikers of the Société des Etudes Scientifiques de L'Aude in 1905, who even gave an illustrated account of it in their bulletin(7).

Passed towards the stream of las Breychos, the cromlech would run alongside the Pic de la Coste and reach a group of loose stones called roulers. Today the rocks are stable, but at the time it was possible to shake them vigorously and make them vibrate; the game would still entertain the hikers of the Société des Etudes Scientifiques de L'Aude in 1905, who even gave an illustrated account of it in their bulletin(7).

The cromlech crosses the stream Trinque Bouteille to reach the marshy area of l'Homme Mort (Haummoor), and turns east along a west-east route on the Goundhill pass. The line stops at the Col de la Sals and towards a place that takes the same name as the rocks south of the Roko Negro: Cugulhou. The eastern side of the cromlech is much more discontinuous, and is marked by only three groups of rocks: the aforementioned Cugulhou, a second to the east of Rennes-les-Bains (la Fajole), and a third at Montferrand, immediately east of the Bazel pass, where the cromlech ends. Boudet then describes a second, smaller cromlech, enclosed within the first:

"Starting from the place of Le Cercle (Circle), halfway up the slope of the first mountain, it follows the Iliète up to the Trinque Bouteille stream, and is outlined on the slope of the Serbaì'rou more near the Blanque and Sals rivers, it resumes at Roukats, to end again in front of the hamlet of Cercle, its starting point.

Above - the main places belonging to the two chromlech mentioned by Henri Boudet: the dot indicates the area where those related to the largest chromlech arise, the triangle those related to the central, smaller chromlech. The diagram facilitates the parallel reading of the key and the map on the left.

The drunemeton of Rennes-les-Bains is therefore not composed of a single cromlech, but of two: we are faced with a circle that encloses another. As for the symbolism of the circle, Henri Boudet will have the opportunity to surprise us again. In the section "Religious significance of the cromlech, menhirs, dolmens, and roulers," Boudet introduces the most "elevated" theme of the book: he goes so far as to argue that the Celts had prefigured the plan of Christian salvation even before the coming of Christ. The hypothesis is entirely fanciful since the Celts were rather a polytheistic people who never achieved religious unity, but for Boudet it represented the culmination of his analyses. The evidence he brings to support this incredible theory is mostly symbolic:

"The circles traced by the standing stones had for The Celts had a profoundly religious sense. The Druids, like the ancient philosophers, saw the circular figure as the most perfect: for them, it represented Divine perfection, immense, infinite, having neither beginning nor end. [...] The centre of the cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains is located in the place called, by the Gauls themselves, le Cercle. By calling the central point of the Redonians' cromlech cercle, to circle and (cerkl') to surround, to encircle, and thus enclosing a smaller circle within a larger one, the Druids wanted to express very clearly the idea that they conceived of a single God existing within beings.

The great monuments would therefore be works erected to a single God, who only a few centuries later Jesus Christ would announce. This is consistent with the priest's previous interpretation, according to which these megaliths were representations of bread:

"[The Celts] had brought back from the East the precise principles of the Divine Being, so they fixed in the ground, by means of upright stones, their thoughts and their belief in God, in whom all things live and move, in God, who dispenses to men through his generous Providence the principal food of bodily sustenance, grain and bread. This is what the menhirs and dolmens that contribute to the formation of stone circles, the cromlechs, indicate. This, of course, would make the Gauls, descendants of the ancient monotheistic Celts, "the chosen people" just like the Jewish people.

Henri Boudet's mystical nationalism (as Lannaccone called it) reaches a point where it reaches its limits when he writes:

"The Celts, being of all the ancient peoples except the Jewish people, the one who had preserved in their traditions the purest doctrine, had to carefully maintain this essential truth of divine government over humanity."

This doctrine, carefully passed down by the Druids, would have become corrupted over time and the Pagan ideas, "the fruit of trade with foreigners," would have obscured the memory of the high religious significance of these monuments. Indeed, writes a horrified Boudet, Caesar even thought these stones were altars where human sacrifices were celebrated. The paragraph on "Human sacrifices in Gaul" opens with a lengthy quotation from the Commentaries, and in particular from Book VI of Julius Caesar's De Bello Gallico:

"The Gallic nation is all very superstitious. For this reason, those who are afflicted with serious diseases, exposed to accidents in battle, and to other dangers, either sacrifice men as victims, or vow to sacrifice them. They employ the ministry of the Druids for these sacrifices. They believe that the favour of the immortal gods cannot be obtained except by offering the life of a man for the life of a man; and they have made the institution of sacrifices of this kind public. They fill the enormous statues of their deities, fashioned from flexible wicker branches, with living men; then they set fire to them, and the men perish in the flames. They think that the torture of those caught in theft, brigandage, or some other crime is very pleasing to the immortals. But in the absence of guilty persons, they even sacrifice innocents."

For Boudet, this testimony is almost completely unreliable; Caesar would not have been able to understand the true meaning of the Celts' gesture:

"We ourselves [...] are astonished by these words of Caesar and by this mysterious doctrine of the Gauls, which states that the life of one man must redeem the life of another to fully satisfy divine justice."

But the priest claims to hold the key to correctly interpreting the Druid doctrine: the death of one man to redeem another brings to mind the story of Christ and the redemption of humanity through his death on the cross. The Celts had only intuited what Christ would later accomplish by offering his life for the salvation of the world:

"Humanity could not divine on its own that the blood it needed was that of a Saviour God, because it did not suspect the immensity of the fall and the immensity of the redeeming love. The true altar was erected in Jerusalem, and the blood of the victim bathed the universe."

This last sentence is taken by Boudet from the Clarifications on the Sacrifices by Count J. de Maistre; according to the priest, the "uncouth" Roman general could never have understood such a truly Christian teaching. The Celts, according to the priest of Rennes-les-Bains, were not only a monotheistic people, but also prophetic, having prefigured in Druid teaching the Christian concept of redemption and ransom of all humanity through the blood of a single man, the Redeemer Jesus Christ.

The next paragraph is dedicated to a stone Boudet calls the "Pierre de Trou" or "Celtic axe," an object made of flint or other minerals, which, according to the author, must have had a specific religious significance. There is no need to dwell on these stones: they were the weapons of Celtic warriors and, as such, were "religiously" placed in their tombs. But for Boudet, they were something more: they were small fetishes to carry with oneself so as to always have a reminder of the highest religious values. As the priest wrote:

"The Celts always had, in every country, before their eyes, the large standing stones that exhorted their will to gratitude towards the Creator, pushing them to ask and give thanks, while the Pierre de Trou stones, easily transportable, constantly admonished them of the religious duties to be fulfilled, of the divine assistance to be constantly implored, especially on the journeys, full of adventures and dangers, which they loved to undertake."

The next paragraph further emphasises the similarity between Celtic and Christian religiosity, to the point that the Druids, "already well-informed through their traditions on the fundamental truths of the true religion, were the first to embrace Christianity, whose doctrines complemented the truths they had preserved intact. Following their conversion, they entered the Christian priestly order and were pleased to maintain their function as dispensers of grain, which accorded well with the precepts of charity of the Gospel."

After quoting Dion Chrysostom, who attributed the knowledge of the art of healing to the Druids, Boudet states that this art consisted in the prescription of certain baths: history offers him on a silver platter the proof that the Celts had considered Rennes-les-Bains an ideal place to establish their residence; indeed, the alleged cromlech contains all the local thermal springs. Throughout the text, the priest precisely records the temperature of the waters, writing: "The springs enclosed within the cromlech are very numerous: three are thermal, at different temperatures. The spring called Bain-Fort has a temperature of +51 degrees Celsius, while the other two, called Reine and Bain-Doux, reach +41 and +40 degrees Celsius."

The short text would play a very important role in the following century: the three temperatures would be expressed in Roman numerals (LI, XLI, and XL) and combined to form a code, LIXLIXL, which would be used as a signature based on a (most likely apocryphal) tombstone of the Marquise Marie de Nègre d'Ables, who died in Rennes-le-Château on January 17, 1781. The tombstone was never found, and today exists only in a series of inconsistent drawings.

In a paragraph dedicated to the Notre Dame de Marceille spring, Henri Boudet deems it appropriate to also mention the most famous spring in the entire region. This sanctuary, linked to the name of Saint Vincent de Paul and so dear to the Bourbons and the Chambord family, is so important on a religious level that it merits a sort of historical "digression," which, however, is not entirely unrelated to Boudet's thought. In addition to deconstructing the name Marceille to glean information about the region's past, the priest believes that the first Christians who settled in the region would have recognised the previous idolatrous veneration of the healing waters and immediately remedied it by placing a statue of the Virgin Mary there to protect them. Boudet also mentions the name of another sanctuary near Caunes, called Notre-Dame du Cros: "There too, under the magnificent spring that flows at the foot of the mountain, a cross had been marked. A statue of the Virgin Mary later replaced the cross near the fountain, and the sanctuary built a short distance away received the name of Notre-Dame du Cros or Notre-Dame de la Croix (Our Lady of the Cross)." The name of this sanctuary also appears in the alchemical poem Le Serpent Rouge. The priest continues by describing the theme of sacred mistletoe, considered by Pliny to be an excellent medicine for any ailment (omnia sanantem). His interpretation of the Breton term "aguillouné" is very curious. This compound word was commonly shouted on New Year's Day in the streets of Brittany (and simply means "augui-l'an-neuf," "mistletoe in the new year"). Infinitely complicating matters, the author writes: "Aguillouné is divided as follows: ague (éguiou) - intermittent fever, nay (né) - no, an adverb of negation, éguiouné. According to this interpretation, mistletoe was a reliable protection against cyclic fevers, and it was used as an infusion in water, undoubtedly with a very prolonged maceration.

Chapter VIII - THE CELTIC VILLAGE OF RENNES-LES-BAINS

The last chapter constitutes the true conclusion of the text. The first paragraph, entitled Celtic dwellings. The Road for the Wagons/Chariots is a summary description of the land where, according to the priest of Rennes-les-Bains, Celtic dwellings were built. His attempt at reconstruction is curious—as well as extremely difficult—and recalls what Louis Fédié did with the citadel of Rennes-le-Château during the centuries of Visigothic rule. The next paragraph, however, responds to an obvious objection: his fanciful phonetic interpretations suggested that the Celts ate grain, but, on the other hand, no historian had ever thought that the Gauls ate primarily this food.

Boudet exhumes the term kaì'rolo, which constituted a kind of granary, which he located south of Montferrand, near the path leading to the Coumee stream at Artigues. This would prove that the use of grain was widespread, despite historians' opinions to the contrary. Boudet also writes that the Celts were great eaters of sheep and cattle, as well as heavy drinkers. The first paragraph dedicated to wild boar hunting treats this activity from a historical perspective, mentioning at one point—for the first and only time—the region of Arcadia; this occurs while he is reporting the memoirs of a 16th-century hunter, Jacques du Fouilloux, taken from a copy from 1834 from the magazine Magasin Pittoresque:

"The Gauls' predilection for wild boar hunting was known to the ancient Greeks, and following their custom of personifying the qualities of the Gallic nation in Hercules, they included his fight against the Erymanthian boar among this hero's twelve labors. [...] Erymanthian, a mountain in Arcadia, was the refuge of a wild boar whose fury filled the entire region with terror. Eurystheus asked Hercules to free the country from this feared guest. Hercules chased the boar, captured it alive, and carried it on his shoulders to Eurystheus. Eurystheus was so terrified that he hid under his famous bronze barrel. The story of the Erymanthian boar is a fabulous image of the boar hunts so dear to the Gauls."

The final paragraph picks up the book's underlying thesis: the Celtic Neimheid gave the rocks around Rennes-les-Bains a series of names that reveal the region's past and the religious significance of the two circular cromlechs surrounding the village.

Precursors of Christianity, the Celts slowly lost touch with the original teachings of the Druids, becoming corrupted and leaving the area to the Romans. The birth of Christ soon brought order: as Henri Boudet writes, "the proconsul Sergius Paulus, disciple of the apostle Saint Paul, came to bring the Gospel to southern Galicia and established his headquarters in Narbonne. The Christian missionaries sent by the illustrious and holy Bishop to win over the minds and hearts of the Gauls of the Narbonne area to the truth, understood, upon entering the cromlech of the Redoni, that the respect with which these carved and raised stones were regarded was a respect that had become idolatrous, and so they had Greek crosses engraved on all points of this stone circle, at the entrance to the cromlech, at the Crossés, at the Roukats, at the Serbairou, on the crest of Pla de la Coste and de las Brugos and at the western Cugulhou. Then, on the crest (a l'arete) of the cap dé l 'Hommé on top of a menhir, in front of the temple pagan, converted into a Christian church later destroyed by fire, a beautiful head of the Saviour was sculpted looking over the valley, dominating all these Celtic monuments that had lost their teachings. The cross, victorious over paganism, has not ceased to reign in the cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains and keeps intact, engraved in the religious hearts of its inhabitants, the precepts of life given to the world by the Eternal Truth.

Critics of the text

Boudet's text, The True Celtic Language, was quite successful and inspired several authors from the region. For example, there are postcards from the area describing the stones "forming part of the cromlech of Rennes-les-Bains"(8). The book reached English libraries: a copy was found by Robert Andrews and Paul Scheilenberger at Oxford University(9), and Queen Victoria, who perhaps read the book absentmindedly (or perhaps didn't even read it), limiting herself to instructing a spokesman to send a letter of thanks to the curate. A copy of the book also reached the former Emperor of Brazil. We know for certain that another copy, preciously bound and with a letter of dedication, reached the Bishop of Carcassonne(10). Boudet received the most heartfelt congratulations (but were they really so "heartfelt"?) from the English secretary and ambassador to France, Lord Zitton, from Queen Victoria's French secretary, Sir Ponsonby, and from Count Al-Jesum, chamberlain of Don Pedro of Alcantara(11).

Naturally, the book was not taken seriously by all the scholars in the area, and indeed, many of them harshly criticised the priest. These criticisms were more than justified, in our opinion. It is worth citing three documents in which Boudet's work is criticised. One of the major critics of the Reverend Boudet was a certain Emile CartaiIhac, professor of Ancient History at the University of Toulouse and corresponding member of the S.E.S.A. in Toulouse since 1880, who, in an article in the Revue de Pyrénées of 1892, wrote: "[The archaeologists of Aude] must be wary of the etymologies suggested by a bold village priest, author of an unspeakable work on the True Celtic Language"(12). The priest of Rennes-les-Bains expressed his disappointment in a letter dated 6 April 1892, in which he revoked his subscription to the Revue(13). But the stone had already been thrown. Mr. Gaston Jourdanne, a radical lawyer and member of the S.E.S.A., published several criticisms against the theories of the priest of Rennes-les-Bains. In particular, it is worth noting the criticism expressed in a sentence dated May 15, 1892, which appeared in an article in the S.E.S.A. Bulletin of 1893, entitled "De quelques étymologies celtiques"(14). These attacks, more or less covertly, continued until the end of the nineteenth century, reaching as far as Paris. In the 1893 Revue des travaux scientifiques, edited by the "Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques" of Paris, the discovery of a notable quantity of megaliths in the Aude region was reported, which "are not at all the work of the Druids, whose doctrine and cults had never penetrated this part of France"(15). But Boudet had by then become accustomed to these criticisms for several years. In 1887, when he submitted his book to the Academy of Sciences and Letters of Toulouse with the aim of obtaining a gold medal, he was dismissed with a rather brusque written report. Rapporteur Lapierre wrote in his ruling of June 5, 1887: "We cannot enter into a detailed critique of this book to discuss the fantastic hypotheses and the gratuitous yet audacious assertions that seem to indicate a very fertile imagination. From an exclusively religious point of view, the author constantly brings in authorities that have nothing to do with linguistics, or at least as we know it today: the Bible, the Latin authors, de Maistre, Chateaubriand, Figuier, etc."(16). The tone, already rather critical, descended into pure and simple derision: "We were not a little surprised to learn that the only language spoken before Babel was modern English, preserved by the Tectosages. This is what Mr. Boudet demonstrates to us thanks to prodigious etymological efforts. The Academy, while recognising in this volume a summa of work that deserves some respect, does not believe it should consecrate with a reward such a bold and novel system of historical reconstruction." Even in light of subsequent archaeological and linguistic findings, it is difficult to disagree with Lapierre's comment: Henri Boudet's book would be found in the "bizarre texts" section, had it not been revived during the 20th century and reread as a treasure map. It must be admitted that its structure allows for this with extreme agility: constant references to hidden meanings (which the English language brings to light), detailed descriptions of geographical locations around Rennes-les-Bains, and even a map, all peppered with mysticism, biblical references, and sensational hypotheses. It's difficult to resist the temptation to over-interpret.

(1) Jean Pierre J acques Auguste de Labouisse-Rochefort, Voyage à Rennes-les-Bains, Paris: Desauges, 1832, pp.501-502.

(2) Nella Lettera Pastorale di Monsignor il Vescovo F. A. Billard del 1889 si legge: "Stamperia Gabelle, Bonnafouse C.ie/ Successori di F. Pomiès".

(3) Giornaledi Melbourne, Australia, citato in Boudet 1886, p. 11 del cap.l I .

(4) Jacopo Garzonio, "Per l'interpretazione dell'etnonimo gallico Tectosages" in Studi Linguisticie Filologici Online 1(2003), pp.253. cit. in Mariano Tomatis, "Rennes-le-Chàteau dalle origini al periodo celtico - Uno studio su Ile fonti storico-documentali" in Indagini su Rennes-le-Chàteau 14(2007) pp.674-681

(5) Anche alcuni dialetti italiani di origine celtica presentano una parola simile: in piemontese spataré è il verbo che significa sparpagl i are.

(6) Mario Arturo lannacone, "Joseph de Maistre e il Nazionalismo mistico nel pensiero di Henry Boudet Contributi per un chiarimento" in Quaderni di storia del le idee 7 (2001) pp.15-32.

(7) Elie Tisseyre, "Une excursion à Rennes-le-Chàteau", Bulletin de la Société d'Etudes Scientifique de lAude, Voi. 17 (1906), ora nella traduzione italiana a cura di Roberto Gramolini in Indagini su Rennes-le-Chàteau 6 (2006), pp.306-309.

(8) AA.W., Cahiers de Rennes-le-Chàteau, Cazilhac: Béisane, vol.l n.3, p.41

(9) Richard Andrews & Paul Schellenberger, Alla ricerca del sepolcro, Sperling & Kupfer, 1997, pp.126 (or TheTombof God: The Body of jesus and the Solution to a 2,000-Year-Old Mystery, 1996).

(10) AA.W., Cahiers de Rennes-le-Chàteau, Cazilhac: Bèlisane, voi. 1 n.3, p.40.

(11) Chaumeil/ Rivière 1996, pp.247. jarnac 1985, pp.280 esegg.

(12) Emile Cartailhac, Revue de Pyrénées, Tomo IV, 1892, pp.l67.

(13) Pierre Jarnac, Histoire du Trésor de Rennes-le-Chàteau, Nice: Béisane, 1985, pp.285.

(14) "De quelques étymologies celtiques" in Bulletin de la Société d'Études scientifiques de l'Aude, Tomo IV, 1893.

(15) Revue des travaux scientifiques, 1893, p.842.

(16) René Descadeillas, Mythologie du Trésor de Rennes, Editions Collot, 1974 (1991), pp.87-88.