The Meridian Mysteries Reposted from HERE - by WILLIAM GLYN-JONES

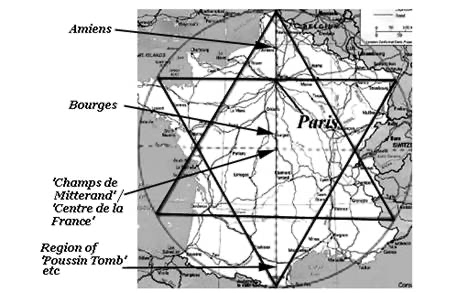

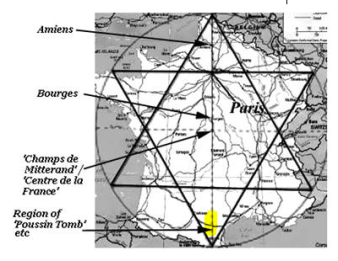

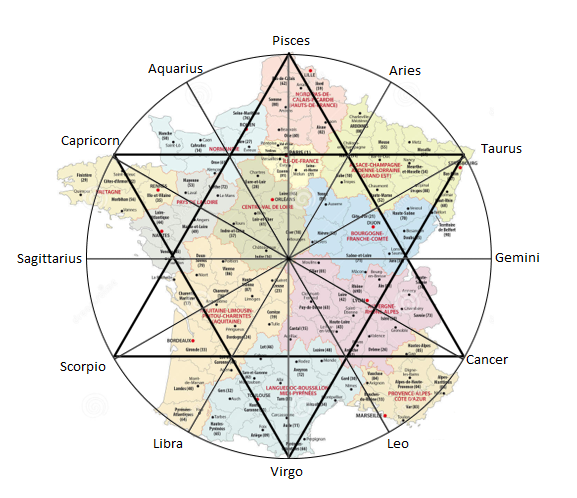

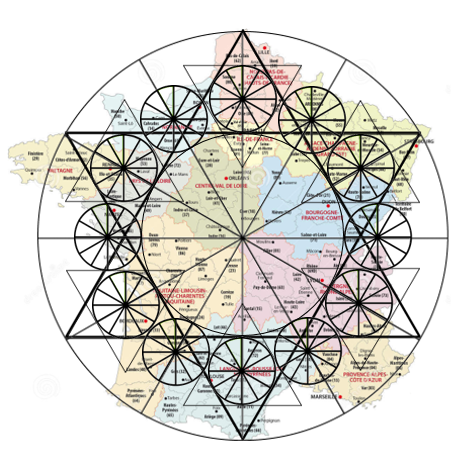

This piece concerns a Hermetic scheme for France, based on a hexagram (Seal of Solomon), where the central vertical axis is the Paris Meridian, and where Paris is at the intersection of the inverted triangle of the hexagram (“the chalice”) with the Meridian (“the blade”).

The hexagram is a geometric figure, and so is a meridian – it being a straight line – so are there not further questions to be asked about the connection between this pattern of the two triangles and the two meridian lines?

And then a thought occurred to me.

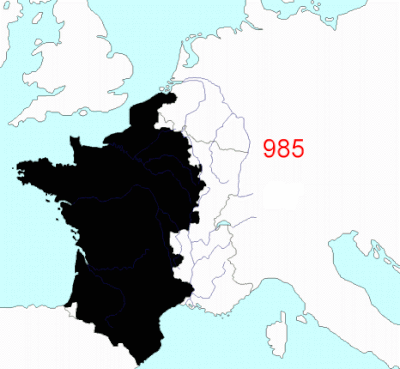

The shape of France on the map is hexagonal.

L’hexagone is actually used by the French as a nickname for their country. I even seemed to recall that there was a French national newspaper that took this as its name, for this reason. It was time to get hold of a map of France. How did the Paris Meridian relate to the hexagonal shape of France?

I soon found a map, and then noted something very interesting. Effectively, the Meridian runs from the North Point of France down to the South Point, and I could also see that the line bisected the nation vertically into what looked like two fairly equal halves. In other words, the Paris Meridian runs from the top tip of the first equilateral triangle of the hexagram down to the bottom tip of the other triangle, the inverted one. I thought again of this business of the intersection of Blade and Chalice. The Chalice is the inverted triangle, and I found myself wondering where the meridian bisects this. Looking at the map it occurred to me that this might actually be at Paris. If so, Paris would be at ¾ of the way along the Meridian line measuring from South Point up to North Point. Well, that wouldn’t be a difficult measurement. I’d just need to measure the length of the full Meridian on the map, multiply by 0.75, and then measure that far up, and see if this pinpointed Paris. I only needed a ruler and a calculator, and I had soon laid my hands on this equipment.

When I made the required measurement I found that yes, ¾ of the way up the line does indeed pinpoint a spot smack bang in the heart of Paris. In other words, the Louvre pyramids and their little brother on the floor below are indeed located at the intersection of the Blade and the Chalice, if the Blade is taken at the Paris Meridian (more on this in a minute), and the Chalice as the inverted triangle formed from the hexagram placed onto the map of France.

I was by now starting to wonder if there was more to this mystery than immediately met the eye.

It might be sensible to ask: how did the map of France evolve towards a hexagonal shape? This could be tricky to trace from reading the history, but luckily it’s already been done and, usefully, a dynamic, animated map is provided on the Wikipedia page here which shows the full evolution with all its stages. I’ve also pasted this at the top of this piece, but if it doesn’t animate in your browser for any reason, you can follow the link instead. This makes it much easier to see the timing, and it is clear that it was during the period between the mid 1600s and the mid 1700s that the evolution appears to show a concerted effort to make the shape of the country hexagonal. This is intriguing because it coincides with the period of Louis XIV – the “Sun King” – and Cardinal Richelieu. The reason this is interesting is because it is also the period when France was first properly mapped, including the establishment of the French Prime Meridian through Paris. From this baseline, triangulations were made to map out the whole of France. It was also a time when France became the greatest power in Europe and so would have found it the most easy to pick and choose their borders.

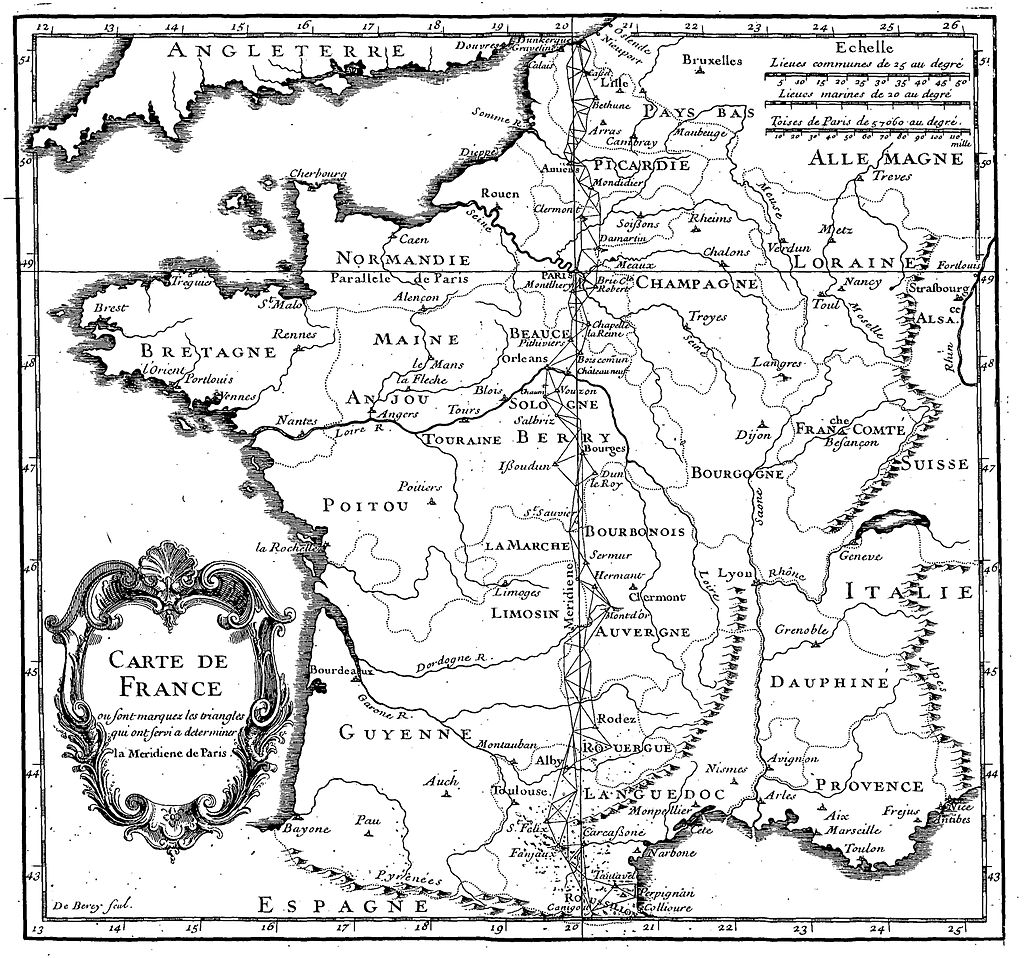

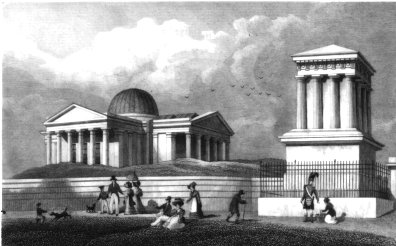

The masterminds behind the French throne decided they wanted France to be properly mapped so that the country could be developed, with roads and bridges and canals and so on, according to a cartographic master plan. The Paris observatory was built just outside Paris, and from here the French Zero Meridian was laid out, upon which the subsequent surveys – the first proper scientific cartographic surveys in the world in the modern sense – were based.

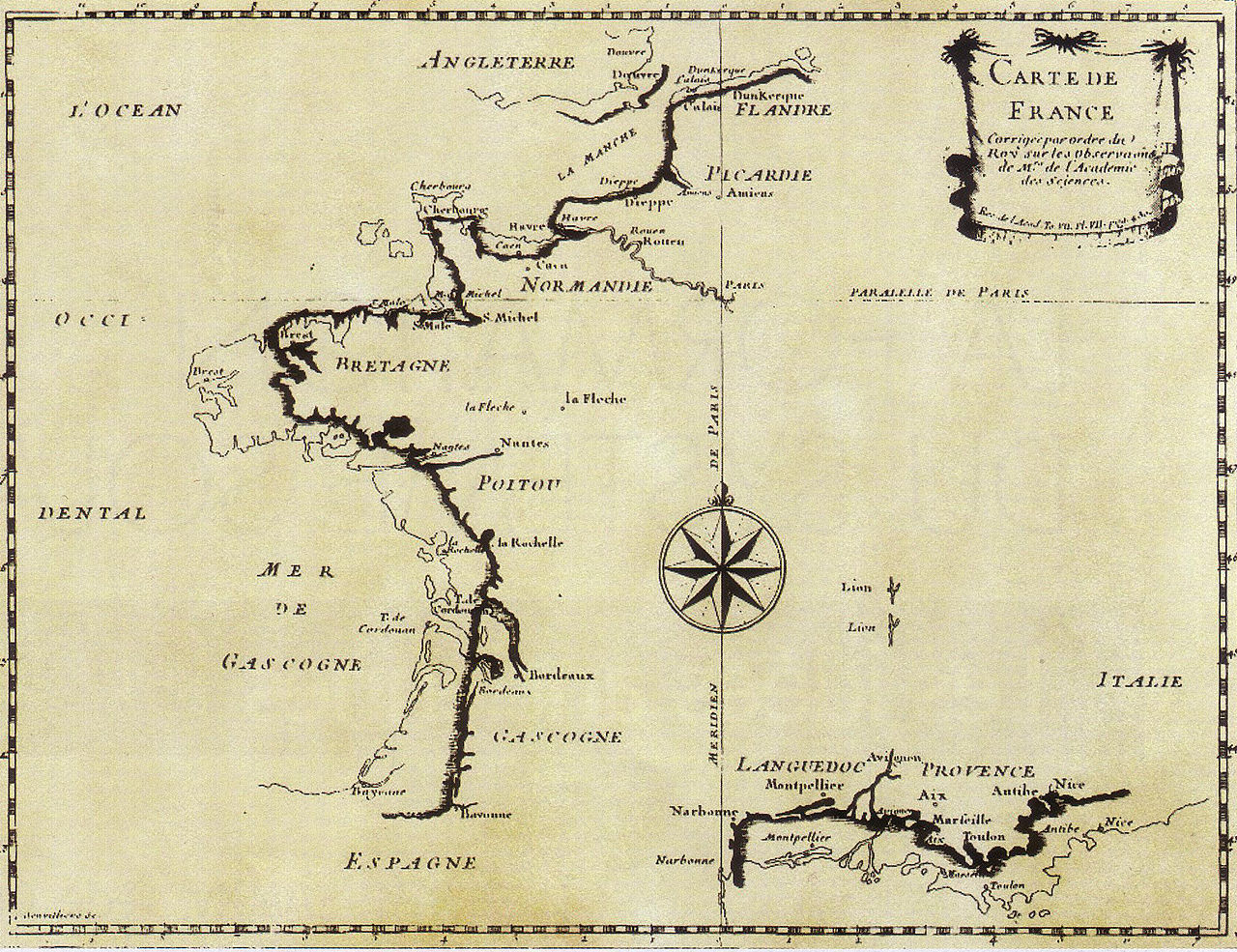

And intriguingly, when we look at some of the early French maps we do indeed see Paris placed at the intersection of the meridian and a horizontal line, the Parellel de Paris.

Map of the French coast, corrected by the Academy of Science 1682

French Map of 1720 showing the Parallele de Paris and also (if you zoom in) showing the Paris Merdian as being at 20 degrees of longitude.

It was also upon the eve of the Revolution that the great cartographic survey of France begun in the Sun King’s time was finally completed. Then when Napoleon came into power the borders suddenly expanded as a result of the conquests. However, after the defeat of Napoleon at Elba a group of European royals and their officials met in Vienna and, as well as taking in the odd Beethoven performance here and there, came up with new agreements about the European borders, and in the case of France this resulted in the shape of the nation reverting as if by elastic memory to a hexagon. It was a royalist meeting that didn’t have democratic aims high on its list, but it did result in about a hundred years of peace between European nations, quite a significant result.

One place where the Meridian and Hexagram mystery shows up is within the Rennes-le-Chateau treasure hunt. In the below we’re even going to make some new discoveries regarding the riddles that were set by those who generated the mystery in the 1960s.

From a morphic resonance perspective, we’re in a somewhat similar position with respect to the Rennes-le-Chateau mystery as we are with the constellation figures. With constellations, we know the mythological figures they represent were not really raised to the stars by Zeus, and also that the stories they come from are just myths; we are confident too, most of us, that they don’t really emit any astrological force. Yet, the very fact that millions of people, in generation after generation, have wondered at them and about them, means that the patterns and the images and the stories of them are richly imprinted with morphic fields.

Likewise, with the Rennes-le-Chateau mystery, we know that it is almost certainly not what it first appeared to be, yet millions of people have felt high degrees of curiosity about it, and again, this must be imprinted in the fields of the idea. It’d be nice to salvage some of that resonance. Luckily, by dipping into older esoteric traditions, the mystery seems to have piggy backed on older mysteries and as such we can still rescue a Hermetic scheme out of it; specifically, it taps into the mysteries of the Meridian and the Hexagram that go back to the seventeenth century. In addition, while exploring the mystery, we just… learn stuff about stuff … if that’s not little over generalised. So let’s get into the questing frame of mind.

There are various very relevant features – and by that I mean references to the matter of the Meridian, the Hexagram and the intersection point between them – in some of the parchments of the Rennes-le-Chateau mystery in elements that are intriguing because they are hidden yet undeniable …but perhaps it’s worth reminding ourselves first what this mystery is and where the parchments are supposed to have come from.

As we look into this business, we need to be aware that the stories comes via various voices in different periods where different agendas were at play, so that the same material could have different meanings within different historical layers.

I’ll be brief. In 1832 the book Voyage à Rennes-les-Bains by Auguste de Labouïsse-Rochefort contained ‘The Legend of the Devil’s Treasure’, which described a great treasure hidden at the remains of Blanchefort fortress, overlooking Mount Cardou and close to Rennes-le-Chateau. He makes it a shepherdess who first sees the treasure. The author of this story became a member of the Arcadian Academy of Rome in the same year that the book was published, saying: “A Shepherd of Arcady by the gentle inclination of my heart, I could not help but want to be a member of this illustrious Arcadian Academy.” In another of his books he started with the motto “Et in Arcadia Ego” without explanation. This introduces the Arcadia theme, albeit it indirectly, at an early stage.

In 1891 the local priest of the little perched village of Rennes-le-Chateau in the foothills of the Pyrenees, in the Languedoc region in the South of France, a fellow name of Sauniere, went from rags to riches. It seems this was this was actually achieved at least in part from donations and by selling masses, but a different story was to emerge in the 1950s, as follows. In the 1940s Noel Corbu became the owner of the properties where Sauniere had resided in the village, and in 1953 he inherited archives relating to Sauniere, and in 1955 claimed that Sauniere had discovered a great treasure. He seems to have genuinely believed there was treasure at the site, but, unable to find it, his agenda also came to include generating interest to attract people to his restaurant. He claimed that Sauinere had discovered parchments while renovating his church “written in a mixture of French and Latin, in which at first glance could be discerned passages from the Gospels”[7] and later saying that Sauinere’s discovery relied on two inscriptions, one on a gravestone in the cemetery and another on a stone found on farmland property close to Rennes-le-Château.

Then in the 1960s a book was published called Le Tresor Maudit (‘The Accursed Treasure’), by Gerard de Sede, which again claimed Sauniere found parchments, saying they were hidden in a hollow inside one of the two pillars that supported the altar of his church, and these parchments contained hidden clues, and it actually published images of the various documents, which were indeed Latin texts of the Gospels with some French added, as Corbu has said, but it is now known that that these documents were created later than the time of Sauniere, indeed the creators admitted as much.

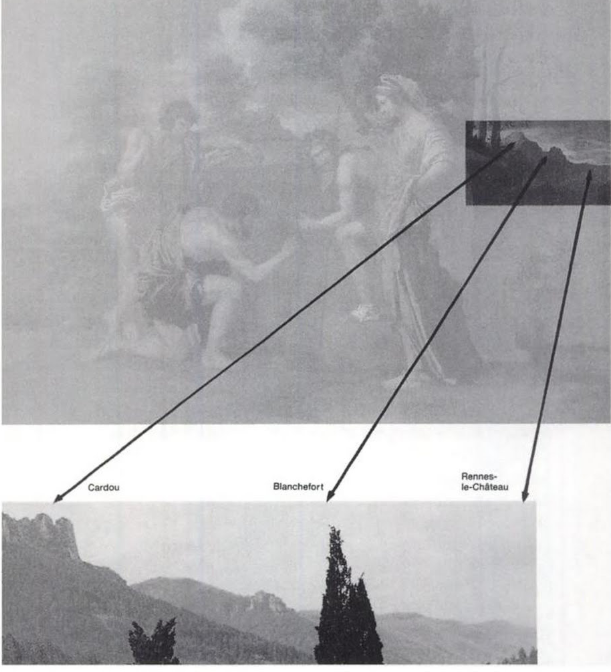

The Et In Arcadia theme became entwined with the mystery more closely where one of the inscriptions that had supposedly helped Sauniere find the treasure was claimed by de Sede and co. to have included the word Et In Arcadia Ego, and in addition a site near Blachefort where a tomb was located was claimed to be the one depicted by Poussin in The Shepherds of Arcadia II back in the seventeenth century. This made the story seem more compelling because it did indeed look similar, as did the shape of the horizon seen from here, compared with the one depicted in the painting, as observred by Henry Lincoln. This remains one of the oddest elements of the mystery, in the sense that it hasn’t been properly explained away, despite the fact that the tomb that was at this site seems to have been built more recently than the time of Poussin. The land appears to have been secured as a burial site by the father of Deodate Roche, who became a Master Mason and had various spiritual and esoteric interests. The possibility that it was a recreation of an earlier tomb exists, because this spot had, prior to the French Revolution, been the site of a cemetery. Further clues claimed explicitly that Poussin had been in on the secret of Rennes-le-Chateau, whatever the secret might be. The tomb was destroyed in the 1980s by the then owner to prevent treasure seekers trespassing. It must be considered a possibility that there is something in this, but whether it meant the same to de Sede, Plantard and de Cherisey as it had meant to Poussin would be another matter.

Gerard de Sede’s book was a reworking of an earlier draft by Piere Plantard, with the parchments having been created by Philippe de Cherisey with Plantard. Gerard de Sede later claimed that Plantard has been receiving money from the Habsburgs (i.e. the surviving Habsburg-Lorraine branch of the old European royal family), who were interested in secret genealogies of descent from Louis XVII, and that the references to Dagobert II’s lineage in the documents were substituted for those of Louis XVII. This is possible: both the Habsburgs and Lorraine families, even before they merged, had claimed descent from Godfrey de Boullion, who first conquered Jerusalem in the Middle Ages and to whom the surviving order of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre traces its origins (as did, allegedly, Plantard’s invented Priory of Sion. This knightly order of the Holy Sepulchre crops up again below as a posible key to understanding images involved in the mystery. Was the Priory of Sion a fictionalised stand-in for the order of the Sepulchre? A parody even?)

What does seem clear is that de Sede, Plantard and de Cherisey and co. did have a genuine interest in esoteric matters, even if the hoax they created had elements of parody, and while there may have been no actual treasure to find, the Poussin connection remains a genuine mystery.

As such, though much of the Rennes-le-Chateau mystery is pure hoax, it does seem possible that it may contain references to secret information that was held by the French royal family prior to the Revolution and passed to the royal European family of Habsburg-Lorraine, including, I assert, the knowledge that in the seventeenth century a plan had been in place to evolve the borders of France deliberately such that the country would assume the talismanic shape of a hexagram, with the Paris Meridian as its central vertical axis, and with the Parrelelle de Paris as the upper horizontal of the hexagram.

The story of the discovery of the parchments in one of two hollow pillars actually echoes the old Freemasonic story of Hermes discovering the antediluvian secrets of geometry and the other arts. “Before the Flood the sons of the patriarch Lamech invented the sacred science of Geometry and all the other sciences… he learned them from his great great Grandfather Enoch the first Mason … as Genesis says he built the first Cities…they inscribed their knowledge inside two hollow pillars, a marble pillar that could withstand fire and a bronze pillar that would survive a flood. One pillar survived the flood and was found by Hermes Trismegistus the great-grandson of Noah who deciphered them and taught its knowledge…to the Egyptians.”

The clues in the parchment make reference to treasure, but this similarity to the story of the antediluvian pillar should perhaps alert us to the possibility that real matter is Hermetic, and geometric, and that the gold is that of inner alchemy. Certainly, the creators of the parchments had a deep interest in esoteric matters including sacred geometry.

The documents and other material supposed to be connected to the mystery, or at least, if not the full list, those that we shall consider, here consist of:

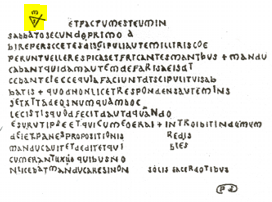

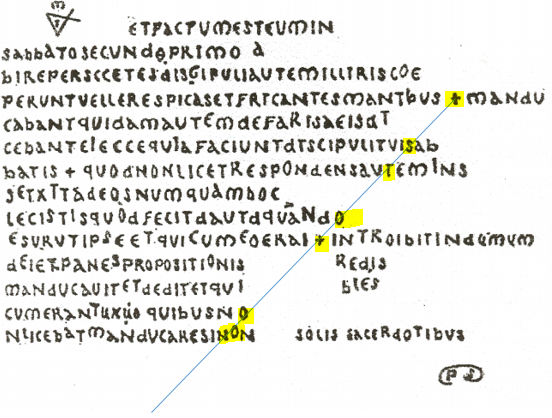

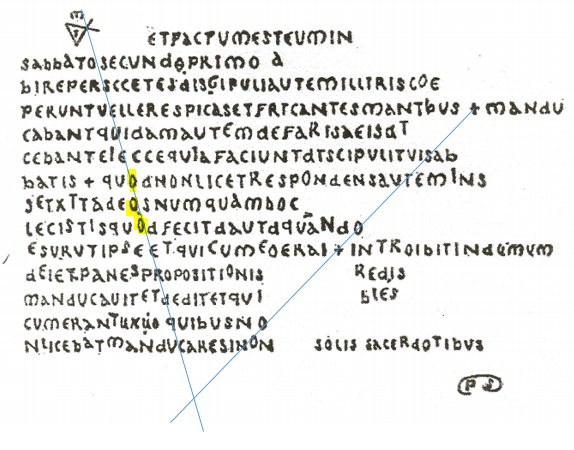

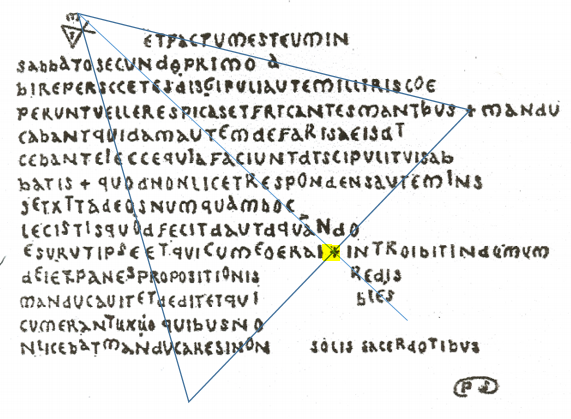

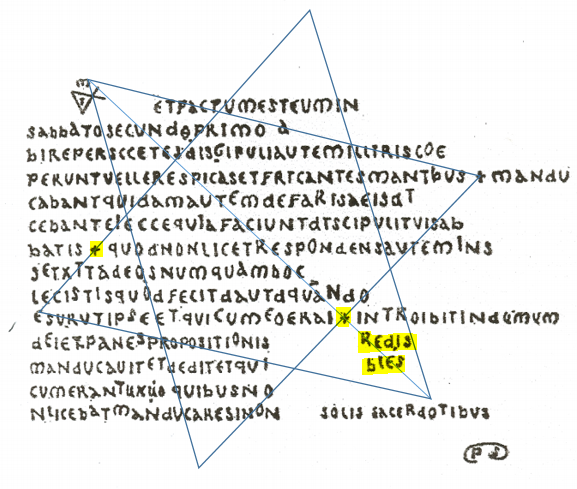

- Parchment 1, a Latin text, a compound of several Gospel versions of the story of Jesus and the disciples walking in cornfields on the Sabbath, but with curious choices of line endings, such as lines ending in the middle of a word even when there is plenty of room for the line to be completed, and also one or two additional words that are not part of the text

- Parchment 2, which is by contrast very evenly laid out as a square block of text, but also with a strange symbol; the text is the ‘Vulgate’ Latin version of the verses of John’s Gospel that describe Jesus’ visit to the house of Lazarus in Bethany, but with many additional letters added

- The Dalle de Coume-Sourde inscription, a pattern and text which were supposedly an inscription on a stone near Rennes-le-Chateau, with a Latin text we shall look at shortly

- The Marie de Negri text, again a supposed inscription, this time allegedly from a tomb stone in the cemetery of Rennes-le-Chateau. Included on this are the words Et in Arcadia Ego – “I also in Arcadia” – the same phrase that is written on the tomb in the Arcadian shepherds paintings

- A text resulting from the solution to a complex cipher contained in Parchment 2. This solution was provided by the same de Sede who wrote the aforementioned book, The Accursed Treasure, but at a later time, in a letter. The clue contains not particularly obscure references to the Shepherds of Arcadia paintings of Poussin and the Temptation of St Anthony by Teniers. The book by de Sede mentioned that Sauniere bought copies of these in Paris

- A geometric image which according to the museum of Rennes-le-Chateau was the personal bookplate of Sauniere

- A section of the Dossiers Secrets attributed to a Henry Lobineau, a mysterious text supposedly compiled by Philippe Toscan du Plantier, a document which was deposited in the Bibliothèque nationale de France on 27 April 1967, and which seems to imply the Lost Tribe of Israel came to France in antiquity.

The realisation that the parchments supposedly found in the pillar contained hidden messages occurred to Henry Lincoln when he noticed a fairly simple encoding. Some of the letters in Parchment 1 are displaced above the other letters in the same lines. Stringing these together in the order they appeared produced a simple message in French which proclaimed the presence of the lost treasure of the Merovingians (and before that, it would seem, the Temple of Solomon):

A DAGOBERT II ROI ET A SION EST CE TRESOR ET IL EST LA MORT

The treasure belongs to Dagobert II and Sion and it lies there.

So, my aim here is not to find some final solution to the treasure hunt, but rather to observe how it echoes the theme of France as a hexagram with the Paris Meridian forming its central vertical axis, with Paris and an intersection between Meridian and Hexagram.

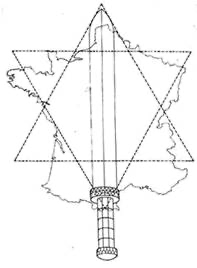

My first observation of a very direct (and really pretty explicit) connection was the cover of Circuit, a small magazine brought out in the 1960’s by the man who claimed to be the secretary of the group calling itself the Priory of Sion, namely Philippe de Cherisey. In Cherisey's image, which predates The Da Vinci Code by half a century, the blade of a sword runs along the Zero Meridian, and the image even has the hexagram placed over the French map.

So this image comes very close to pre-empting the scheme I believed myself to have uncovered, but it managed to obfuscate the revelation by distorting the relationship between the hexagram and the meridian. In Cherisey's image the bottom of the hexagram is exactly on the southern border, but, presumably so as not to give the secret away too easily, he has not made the top of the hexagram map onto the north point, thus hiding the fact that Paris is at the intersection point. The existence of a Priory of Sion was of course created by those who orchestrated the famous Rennes-le-Chateau mystery.

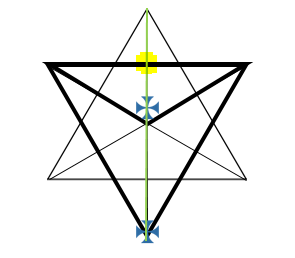

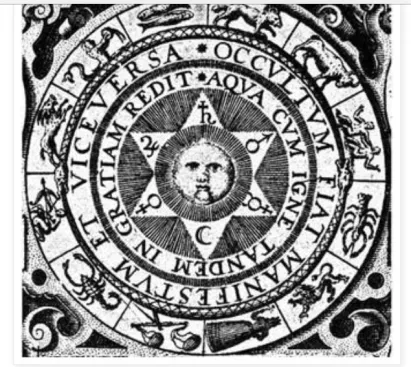

The next observation was that the hexagram / Seal of Solomon / Star of David pattern, with, moreover, an intersection point highlighted, is present In the bookplate supposedly used by Sauniere, the priest who is said to have discovered the treasure and the secret parchments of Rennes-le-Chateau. (A bookplate is a small print for pasting inside the cover of a book, to show who owns it. This webpage has more on this bookplate: “The Ex-Libris [bookplate] was taken though from an early Rosicrucian book by Adrian von Mynsicht (1603-1638) a German Rosicrucian alchemist (Dei Gratia Aureae Crucis Frater) known for his allegorical work Aureum Saeculum Redivivum[The Golden Age Restored], and published under the pseudonym Henricus Madathanus around 1625.) Look carefully and you’ll see the dot in the centre of the cross is in the Paris position, a direct reference that, it seems to me, cannot possibly be just coincidental, and the other dot in the middle of the concentric circles at the other intersection point along the central vertical/meridian. The words around the circle around the dot translate as “the centre of the triangle of the centre.” For more on this see here.

Sauniere’s Bookplate based on the Solomon Seal

I decided to look further for more echoes of the Meridian and the Hexagram with the Rennes-le-Chateau material, and soon found another. This is found is on the Dalle de Coume Sourde. The pattern and text supposedly on this stone look like this:

The text translates as:

In the middle of the line where M cuts the short line.

Since the two Maltese cross symbols are like abbreviated compass roses, M can be taken here (as has previously been suggested) as the Meridian. Since the line between the crosses runs down the centre of the pattern, it seems sensible to ask whether the pattern has anything to do with the hexagram. The answer is that the hexagram with lines radiating from the centre does indeed generate a the Dalle de Coume Sourde pattern, as shown by the darker lines here.

No doubt someone else has observed before that these crosses are probably compass roses, and that the M represents the Meridian, but what I think is relevant here, and the point really worth making, is that the pattern itself derives from the hexagram, and that the point where the M (meridian) cuts the “short line” (referred to in the text) could certainly be interpreted as the intersection of the Meridian with the horizontal of the triangle, in other words the Paris point, where the Meridian and the Paris Parallel intersect. It might seem a little odd to call this horizontal the “short Line”, but out of the two lines, the meridian itself and this side of the triangle, it is the shorter.

Certainly, this geometry is the same as that depicted on the image that was supposedly Sauinere’s personal book plate, as just examined above.

It is with this is mind that we can now go back to Parchment 1, and make what as far as I know is a new discovery.

It concerns the little symbol with m and I in the top left.

I presume it has been observed before that this is actually an inverted small case Greek omega, with the middle vertical extended, and that its use here may have been seen as having some connection to the omega symbol that is on the pillar that supported the old alter in Sauniere’s church (where the parchments were supposedly found), and which together with an alpha represented Christ as Beginning and End, Alpha and Omega. Sauniere inverted this pillar when he moved it to the garden, also adding the inscription MISSION 1891. The riddle-setters perhaps wanted to imply that this stone itself had a reference to the Meridian, and to the letters SION at the end of MISSION.

The altar pillar with Alpha and Omega.

Having found that the Dalle pattern derives from the hexagram, it seemed to me that the same question should be asked about this little symbol on the top left of Parchment 1. Does it derive from the hexagram? And if so, is it one where a line through the middle of the m and down through the I below it would be in the position relative to the hexagram that the Paris Meridian is in relative to France? The answer to both of these questions is a simple “yes”.

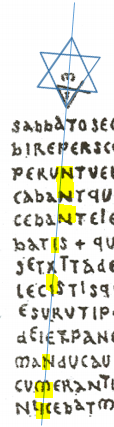

In fact, if we follow this meridian line down, it passes through the left upright of three Ns in a row before finally passing through the middle of anther m and the I immediately below it, i.e. repeating the m over I arrangement at the top, as well as two other Is and another N vertical along the way, as shown here highlighted in yellow.

This m-in-hexagram also surely gives us some insight into what groups may have had an an influence behind the scenes, because this same ‘m’, shaped like an inverted omega, is found in this same position within the hexagram seal of the French mystical-masonic Ordre Martiniste Rectifié (O.M.R. – the ‘m’ here stands for martiniste). Different branches of Martinism have used hexagram symbolism variously for magical invocation, exorcism and quiet meditation.

Hexagram seal of the Ordre Martiniste Rectifié with “m” in the centre of the hexagram

The next feature of note concerns another hexagram hiding within the text. This one has been noticed before (for example by Andrews and Schellenberger in The Tomb of God), but what I want to draw your attention to is the way that this displays the location of Rennes-le-Chateau within the map of France.

Stage 1 is to draw a line joining two of the crosses (+) that have been added to the text. This passes through the letters S, I (actually a T that looks like an I), O, N, spelling SION, just as the last letters of the last four lines also spell SION, and indeed Sion is in the message hidden in this text: To Dagobert II, King, and to Sion etc.) The line also passes tangentially between two elongated 0s.

Next we notice that there is another line that can be drawn that will similarly be tangential to a three more of these elongated 0s.

We then observe that if we add a third line we can make an equilateral triangle out of this such that the middle added + on the initial line bisects that line, and so also a line to it from the opposite corner bisects that angle.

Now, since we know from the little symbol top left that the hexagram is relevant here, we can then add a second triangle to form a hexagram, and in doing so notice that it goes through the remaining additional +, as shown here:-

That much has been noticed before. But now for some additional observations relating to the Meridian and the French Hexagram. Looking at the hexagram now, we can see the + that is half way along the original line is actually at the intersection of the Meridian and the hexagram, as with the Paris point. The Meridian also passes through the words Redis Bles. As has been observed before, these are added words, not part of the biblical text that makes up the rest of the parchment. We can observe additionally that they have been displaced over to the right of the main text. Bles, as has been observed, can be a slang word for treasure, and this makes sense since the hidden message in this parchment is about treasure. What about Redis? This was actually an earlier name for Rennes-le-Chateau, as has also been observed before. But now that we are able to see that the hexagram represents the map of France, with the bisecting line being the Meridian, we can see that this places Rennes-le-Chateau in the parchment hexagon in the same position that it is placed on the map of France, as can be seen by comparing the two images below:

As such, the message and the map together are saying that the ‘treasure’ is located near Rennes-le-Chateau, but on the Meridian. This leads on to Parchment 2, or rather its deciphered message, which was revealed as:

Bergere pas de tentation, que Poussin Teniers gardent la clef, Pax DCLXXX1. Par la croix et ce cheval de dieu, j’acheve ce daemon de gardien a midi. Pommes Bleues.

Shepherdess no temptation, Poussin, Teniers hold the key. Peace 681. By the cross and this horse of God, I complete this Demon Guardian at midday, Blue Apples

Here we’re on territory that has been covered by many before. Lincoln was informed by Gerard de Sade et al that there was a tomb at Pontils near Rennes-le-Chateau which was the one depicted in Poussin’s Shepherds of Arcadia II. The site of the tomb is pretty much on the Meridian, at longitude 2.34 (where the Meridian is 2.337.) The resemblance is certainly excellent…

Pontils tomb

…but what Lincoln discovered when he visited the spot and looked in the direction of view in the painting was even more intriguing: the horizon outline of crags and hills also matched the painting.

Sidestepping all questions of the history behind this, we might ask: if there is some connection between Poussin’s painting and the Meridian, what might it be? What the shepherds have found is a memento mori, a reminder of their mortality. On the tomb are the words Et In Arcadia Ego. The implication is “I too, once, was young like you, frolicking around without a care in the world like some Arcadian shepherd, but now I’m in the tomb. And the same fate awaits the rest of you.” And in the Christian medieval world the significance of this is “Even if death seems far off, start to prepare for it spiritually.” When you consider the Third Degree initiation in Freemasonry you find a connection between such ideas and meridians, via the solar myth, where the Sun is cut down in his prime.

In the Third Degree initiation, the candidate is struck a mock blow as a dramatisation of the Freemasonic story of the murder of Hiram Abiff, who was in charge of the masons who were building the Temple of Solomon. He was killed by a figure standing to the south at noon holding a plumb bob. What such a figure is really doing, clearly, is the mason’s first task of setting out the north-south axis of the temple by aligning it to the Sun’s position (or shadow) at noon. The Sun rises higher and higher through the morning, but when due South, at the meridian of the sky, that is the moment when the ascent stops, and the descent begins. So it’s as if the Sun has been wounded at that point, cut down in his prime. Or you could say, at his Prime Meridian. In Freemasonry the candidate is then further guided to consider their own physical mortality – and spiritual immortality – and the masonic skull and crossbones symbol here functions as the memento mori. The allegory here then is: even when you are at your prime, and death seems far away, don’t think that you don’t need to consider spiritual matters, such as avoiding sin, because death is still coming in the end, so you’d better be prepared for judgement at the pearly gates. Et In Arcadia is in this sense really: “even at your prime”. (Which in the case of the Sun is the Prime Meridian). Or: “I too was once in my prime, like you….” It could even have a political meaning: even the king is not above God’s laws.

However, we want to be careful that we don’t fall into the trap of seeking some final, decisive solution or interpretation of the Rennes mystery. It is really taking us on a journey, where the journey is the goal.

And the next stage in this journey is to ask what Teniers has to do with these matters? The message implies that there is some connection not only to Poussin’s shepherds paintings, but also Teniers’s temptation of Saint Anthony paintings. And while other have tried to find a particular version in which to find geometric clues to the location of treasure, I think we should take a step back and simply observe that the theme is very similar. Like the shepherds observing a tomb with a skull on top in Poussin’s first Arcadian Shepherds painting, Saint Anthony always sits before a rock-cut altar on which are placed a skull and a crucifix. He is using the skull in the manner in which memento mori were used in the Middle Ages: helping himself to overcome the temptations of the works by reminding himself of the importance of spiritual matters, given that the tomb is not so far away.

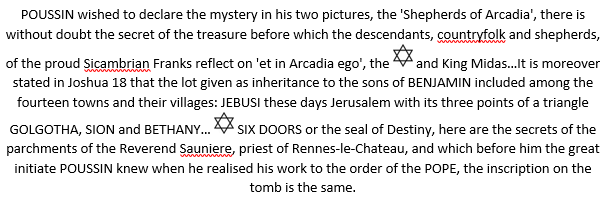

But the skull in these paintings in shown at the base of a crucifix, and in art this is used to refer to Golgotha, the “Place of the Skull” that the Bible says is where Christ was crucified. The reason for thinking this might be relevant is found in another of the mysterious documents, the Dossiers Secrets, since these mention Golgotha:

If we consider this idea of Golgotha being at one of the points of a triangle, plus the fact that it is at the base of the crucifix, and then return to look again at the alleged Sauniere book plate, an idea begins to crystalise.

Here, there is a crucifix at the crossing point of the meridian and Paris parallel – assuming this is a map of France – and there is a circle around the region below the crucifix. The centre bottom of the pattern is therefore both at one of the points of a triangle and in the place of the skull, at the base of the crucifix.

Furthermore, the Golgotha site is linked to a rite that, like the Freemasonic third degree, but before it, involved contemplation of the ultimate memento mori: the tomb of Christ. The traditional location (since the time of Constantine) of Golgotha is a few steps (about 45m) from the spot that has been held traditionally (since the same time) as the location of the tomb where Jesus’ body lay in the tomb. The site for both of these is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There has been since the Middle Ages, and still is today, a knightly Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem. (This is a real one, not Plantard’s made up Priory of Sion. Have a look at the website here.) The knighting ceremony took place before the site of the tomb itself. This is where new knight would kneel for the dubbing ceremony. The night before, he had to hold a vigil at the site. This meant fasting and praying.

A connection with the memento mori would have been inevitable, because during the vigil you were contemplating the mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection, and you were doing so at Golgotha, “the Place of the Skull.” The skull is the most common reminder of death.

The first two Et In Arcadia paintings, the original by Guercino, and also Poussin’s own first version, both feature skulls being contemplated by the shepherds. In the Poussin the skull is located on top of the tomb.

Detail showing skull on tomb in Poussin’s Shepherds of Arcadia I,

and Guercino’s Et In Arcadia Ego, with shepherds contemplating a skull

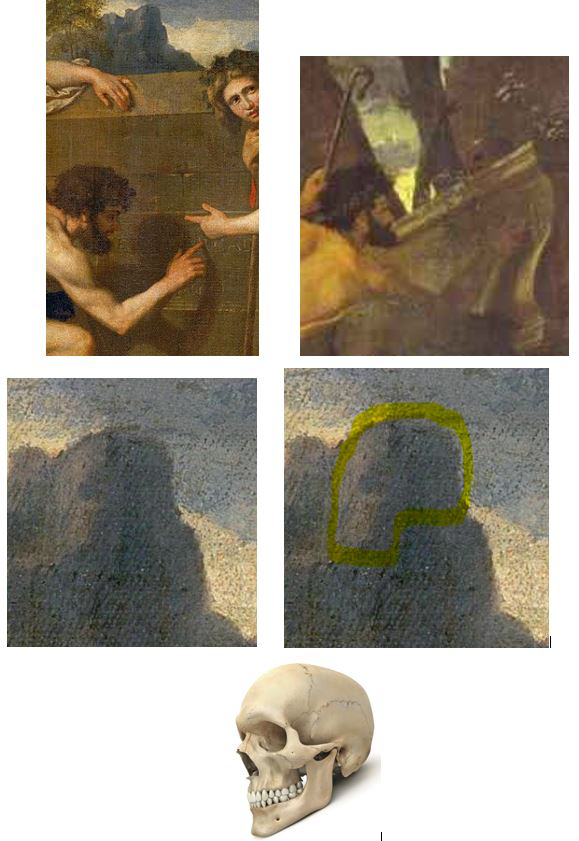

This skull was a truly central feature of these paintings. But though the feature was central to the first two Et In Arcadia paintings, there is no skull in the third, Poussin’s Shepherds of Arcadia II¸ which is strange. Until we take a closer look.

Look at this close-up below of the mountain peak behind the tomb. There in the formation of the rock is the simulacrum of a skull-like head, looking to the left, as with the original, and similarly above the tomb, with perspective subtracted. There is the dome-like top of the head, the shadow of the eye socket, the hollow of the cheek below it, a hint of a mouth with the chin below. I don’t know if anyone has noticed this before, but I’ve not read of it.

As widely recognised, this tomb recalls the tomb of Daphnis in Arcadia in Virgil’s eclogues, but if we are trying to bring a Golgotha theme into the picture, we could say that because Daphnis was the ideal shepherd and Christ called himself the Good Shepherd, and because Virgil’s fourth eclogue was seen as a prophecy of the birth of Christ since as early as the time of Constantine, Daphnis here could be seen as alluding to Christ, so that this is really the tomb of Christ. One of the shepherds is kneeling before the tomb in Poussin’s painting, just as the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre knelt before the tomb of Christ when they were knighted.

As widely recognised, this tomb recalls the tomb of Daphnis in Arcadia in Virgil’s eclogues, but if we are trying to bring a Golgotha theme into the picture, we could say that because Daphnis was the ideal shepherd and Christ called himself the Good Shepherd, and because Virgil’s fourth eclogue was seen as a prophecy of the birth of Christ since as early as the time of Constantine, Daphnis here could be seen as alluding to Christ, so that this is really the tomb of Christ. One of the shepherds is kneeling before the tomb in Poussin’s painting, just as the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre knelt before the tomb of Christ when they were knighted.

So within an overall hexagonal scheme that represents the New Jerusalem, the southern end of the Paris Meridian is being connected with Golgotha. In Catholic countries it is common for a town to mythologise a local hill as a “calvary” (the Latin translation of Golgotha, “Place of the Skull) with stages along the route representing the “stations of the cross”, i.e. particular stages along the journey Christ walked carrying his own cross to the place where he was crucified. In the region of the Pontils tomb and Rennes-le-Chateau the obvious choice is Mount Cardou, as it is dome shaped, and thus reminiscent of a skull, and in fact the Prime Meridian passes through it. So this is the Calvary not just on a local scale, but on the national scale, a place one might visit in elegiac mood to contemplate mortality and the mystery of resurrection. If you want to look into this further, Lincoln in his book The Holy Place viewed Mount Cardou as the solution to a rather cunning pictorial riddle Sauniere had set up within his church be means of, yup, images of the Stations of the Cross. Mount Cardou is also the place where Andrews and Schellenberger homed in on in their quest in The Tomb of God, reasoning by their own logic that this was the place of the tomb of Christ, but whether this was more by luck than judgement, I’m not sure. My own stance, as I say, is not this it is the actual tomb of Christ, but that it represents its location in a scheme of geometric/mythic geography.

But what about the rest of the message?

Pax DCLXXX1. Par la croix et ce cheval de dieu, j’acheve ce daemon de gardien a midi. Pommes Bleues.

Peace 681. By the cross and this horse of God, I complete this Demon Guardian at midday, Blue Apples

Some of this does have a fairly solid interpretation, again related to the Meridian. Since the message has been so far about French painters, Poussin and Teniers, and since the Dossiers Secrets make mention of Saint Sulpice church in Paris as being important in the (fictional) history of the Priory of Sion, it does not seem unreasonable to suggest (as I believe has been done before) that “La Croix” refers to the French painter Delacroix and the Horse of God refers to his painting, which hangs in Saint Sulpice church, The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, especially as this depicts treasure from the Temple of Solomon – the Rennes mystery is a treasure hunt, after all, where the treasure belongs “to Sion”.

In the Bible, Heliodorus was trying to steal the treasure, but God sent a horseman to drive him from the temple. This can therefore without any logical inconstancy be called the Horse of God. And Saint Sulpice is very close to the Meridian (2.334 c.f. 2.337), and has a gnomon inside it, an obelisk where, to quote Wikipedia:

‘A meridian line of brass was inlaid across the floor and ascending a white marble obelisk, nearly eleven metres high, at the top of which is a sphere surmounted by a cross. The obelisk is dated 1743. In the south transept window a small opening with a lens was set up, so that a ray of sunlight shines onto the brass line. At noon on the winter solstice (21 December), the ray of light touches the brass line on the obelisk. At noon on the equinoxes (21 March and 21 September), the ray touches an oval plate of copper in the floor near the altar.’

So here we have the connection to midday in the message, and by changing “De la croix” to “par la croix” the message also plays on the phrase “by this cross you shall conquer” as depicted in the church in Rennes-le-Chateau. Sauniere had this made. Though other examples of crouching devils supporting fonts are known in other churches, the four angels making together making the sign of the cross on top of the font supported by the devil seems to be unique.

Acheve meaning “complete” can also be a euphemism for “kill” so with a killing taking place at noon we’re back to Hiram Abiff, but in the Rennes-le-Chateau context the strongest resonance is with that story from Voyage à Rennes-les-Bains by Auguste de Labouïsse-Rochefort, from 1832, about the Devil’s treasure, where the wizard who is trying to take the treasure from the Devil uses geometric figures during the fight:…..

'The wizard wasn’t a fool, he specified first that he was to be given half the treasure when when it had been attained, and that beforehand he needed four or five hundred francs to prepare for his journey. The money was counted out, they set out, they arrived. The wizard warns them that he is going to fight against the Devil, and that when he calls, somebody must come to his aid to defeat the Devil. – Everybody promises to be brave and go to their places. The wizard makes some passes, invocations, threats; he traces circles and strange figures. Suddenly a great noise is heard… The people become frightened; they flee… As if from a hail of shots or stones!… In vain does the wizard cry for help, Help me! Help me!… He is left calling, with the outcome of the conflict unknown. – He reappeared at last, a long time afterwards, unhappy, panting, covered in dust; he complains that he was abandoned, that he had already overwhelmed the Devil once and that if someone had come running to his call, victory would have been achieved… and the purse gained…..

So we have been whisked back north to Paris, near to the crossing point of the Paris parallel and the Meridian, and one cannot therefore avoid the suspicion that we are being led on a merry dance, but it is a dance that makes us curious about the Meridian and the Hexagram, the hermetic-geodetic scheme of France, and that curiosity then imprints the morphic fields, enriching the sense of place with transpersonal resonance.

But what if you find all this business of skulls and crucifixion a massive downer, rather dark, gruesome even, and not the kind of mythologising that you want for your landscape? Well, there’s another way to look at Cardou. The universal, Hermetic landscape in the sky has a hill with its peak due south. This is the hill the Sun climbs each day. So if you’re bringing this archetypal landscape down to Earth, grounding the Universal into the Particular, then it makes sense that there would be a big hill on the Meridian down to the South. Cardou can play this role for the French meridian. Another thing that you may prefer, that comes out of this stuff, is the French Zodiac. More on that below.

There remains the intriguing question of how the Louvre pyramids could be a key to all this, when they were built only recently. Cherisey's map with Meridian blade and hexagram, and also Sauniere’s bookplate, give evidence that this scheme was known by some in recent times, which also makes it possible that the builders of the pyramids did have this same scheme in mind. In fact, the Louvre pyramid complex was commissioned by President Mitterand as part of his Grands Travaux or ‘Great Works’ programme, which also included the intriguing Monument to the Rights of Man and the Citizen. This monument includes, amongst other things, two bronze figures based on the shepherds in Poussin’s painting, a shaft aligned to the Sun due south at the Summer Solstice, Masonic symbols and two obelisks.

In light of this it would be difficult to claim that the Grands Travaux project including the Louvre pyramids lacked occult significance! The Travaux project also includes the massive Grand Arch of the Defence in the shape of a giant cube. In fact, the glass pyramid was actually the fulfilment of a long-standing plan for a Parisian pyramid, with various versions of the plan being the ‘Cenotaph dans le genre égyptien’ of Etienne Boullée, and the great pyramids planned by the Freemason Nicholas Ledou. Indeed even before Napoleon, during the reign of Louis XIV a pyramid to the glory of the Sun-King had been proposed for the Cour Carrée of the Louvre by architect Francois Dubois, and later a large baroque pyramid with a statue of Napoleon on top was designed by the architect Louis-Francois Leheureux to be located on the exact spot where the glass pyramid now stands. Details of these plans are given in the penultimate chapter of Talisman, the 2004 book of Bauval and Hancock. It seems that whether it was the king or the emperor of a republic – or indeed a 20th century president – was far less important than the real aim – to get a Paris pyramid erected here. This was partly because they believed that the Great Pyramid of Egypt stood on an Ancient Egyptian prime meridian that bisected the Nile Delta. But what ultimately got built also had the inverted pyramid, a symbolic reference, it would now seem, to the location of Paris at the ¾ intersection point along the French Meridian.

The Mystery of Shugborough Hall

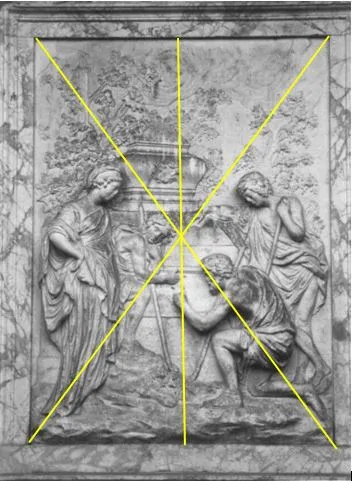

If Poussin’s Shepherds II painting really does have some connection to these Meridian Mysteries, what significance is there in the fact that a copy of this painting was produced in stone relief on a mysterious shrine in the gardens of Shugborough Hall in the English Midlands?

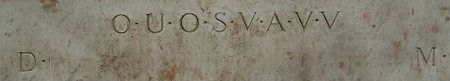

The Image from the Shugborough Shepherds Monument

So, the same Poussin painting that we looked at in connection with the French Meridian, The Shepherds of Arcadia II, is copied, with some variations, in the Shepherds Monument of Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, north of Birmingham. Another link with the French scheme is that a pyramid has been added above the tomb in the image, just as it has been built in Paris.

If we add in a central vertical axis to the image, we can then see the shepherds are pointing at it, with the thumb of the kneeling shepherd extending along it. Could there be a reason for this?

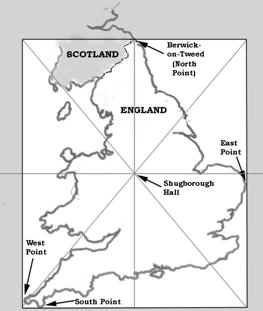

Shugborough is at 2 whole degrees west of the Greenwich meridian, so that the Sun is due south exactly eight minutes later than at Greenwich. If this longitude line is extended due north from Shugborough, it goes directly through the town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, the sharply defined northernmost town in England, also at exactly 2 0’0” West. So just as with the Scottish and French geodetic schemes, Shugborough is on a meridian line that extends to the northernmost point in the country. And what is more, it seems that this longitude line was chosen as the one on which the north point should lie because it is exactly half way between the most easterly and most westerly longitudes of Britain. So there can be little question that, while Greenwich was chosen for the global prime meridian, it is unquestionably this other longitude that is the central geodetic meridian of England.

Shugborough Hall, therefore, is both halfway between East Point and West Point and also close to halfway along the north-south axis between English South Point and English North Point.

Could it even be that its positioning half way between British East Point and West Point was what governed its choice as the English ‘Rose-Line’, and that the English border was then extended north to the point where this meridian line touched the coast, and this place brought within England for this reason, to make it the northernmost point?? The English royalty negotiated a special deal giving the northern-most town of England (Berwick-on-Tweed) a unique dual Scottish-English status, so that it could be ‘of England but not in England’, suggesting that the English really wanted this town even if it meant bending the rules of nationality. James IV of Scotland is reputed to have proclaimed this dual status as he crossed the bridge of Berwick on his way south to be crowned James I of England.

The Greenwich Meridian

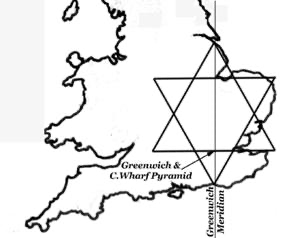

What comes as a real surprise is that similar mysteries pertain to the current international Prime Meridian, that of Greenwich in the East End of London. As with the Louvre in Paris, London too has its modern pyramid, namely the one that is raised up high on the top of Canary Wharf on the Isle of Dogs not far from Greenwich. The Greenwich observatory was designed by Sir Christopher Wren for Charles II as a counterpart to the Paris observatory built for the Sun King, the one that had the meridian going through it, and in England too the meridian goes through the observatory.

And sure enough, if we measure along the Greenwich Meridian line from where it reaches the sea at the south coast and to the north at the entrance to the Humber Estuary, we then find that Greenwich, where this line crosses the great old Thames just east of the Isle of Dogs, is ¾ of the way along, a repetition of the same Seal of Solomon ratio as used in France for Paris! This line is where international time begins and ends, reminding us of Blake’s line telling us how all things begin and end on Albion’s druid rocky shore, and this Seal of Solomon pattern of course links into a once widespread Blakean tradition of London as some kind of New Jerusalem.

OK, so thus far in this piece the direction has been from mystery towards discovery, what we might call an unravelling, the shedding of light. The thing seemed to be resolving into a fairly clear picture: starting in the mid 1600s, there appears to have been a plan to make the map of France hexagonal, in accordance with the Parallele de Paris being 3/4 of the way along the Paris Meridian, from French north point to the meridian’s south point. The thinking behind this was then either rediscovered or passed down, and it formed part of the material used in the Rennes-le-Chateau mystery.

However, when we proceed further, we get to a point where more questions get thrown up than get answered. But let’s proceed into this mystery anyway.

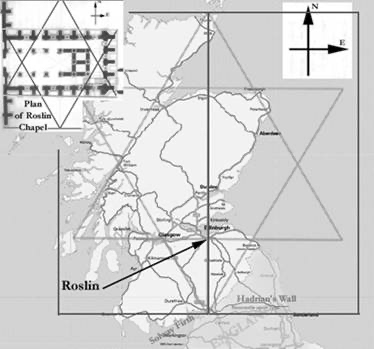

The Roslin Mystery

One questions I asked myself back towards the start of all this was that of how the site of Roslin in Scotland came into these matters. Dan Brown introduces the concept of a Rose-Line and then he tells us this line if extended further south goes through Glastonbury. I checked this out and soon discovered it to be nonsense. It doesn’t go anywhere near. It does of course go north through the Scottish capital of Edinburgh, and I also noticed that, as with France, it goes to a point on the north coast that could certainly have been regarded as the effective North Point of Scotland. Since Roslin is also connected by Brown with the Seal of Solomon pattern, (following, or rather loosely inspired by Lomas and Knight in The Hiram Key) it was perfectly obvious what I had to do. Worth a quick look, I decided. So I measured the ratio, and found with some surprise that yes, Roslin is exactly ¾ of the way along this Scottish “Rose Line”, this time measured from the North Point down to the southernmost point on this longitude line, where it meets the sea at the Solway.

In fact the longitude of Roslin, 3°9’36.72″ West (of Greenwich), runs directly up through Arthur’s Seat in Holy Rood Park in the centre of Edinburgh, as can be seen using the Google Earth gridline feature. This notable landmark, Arthur’s Seat, which dominates the city, is the highest of a set of peaks that form the image of a crouched lion, which is why the hill is also known as the Lion’s Head. The name Arthur’s Seat may indicate an old association with King Arthur. (An early Welsh poem recorded in the 14th century, which mentions Arthur, describes the heroes feasting for a year at Edinburgh.) With this being the highest of Edinburgh’s seven peaks, one could understand the logic of the Meridian being made to pass through it, as the plotting out of the line would have required the sighting of distant landmarks.

Arthur’s Seat seen from Edinburgh’s port of Leith

And just as Paris had a royal observatory from which the French national meridian was plotted out, and as the Global Prime Meridian goes through the royal observatory in Greenwich, there is also a royal observatory in Edinburgh, which originally stood on Calton Hill. Brian Hooker notes in his essay A Multitude of Prime Meridians on the Internet that from the start of the 1700s it was quite common for countries to select the longitude of their national observatory as their zero meridian (and visa versa?). The history of the Edinburgh observatory can be traced back through the first lectures in Astronomy at the Edinburgh University in 1583 through to the establishment of a Chair of Astronomy there in 1786, and the Calton Hill observatory was granted royal observatory status in 1822 by George IV of Britain, who, we may note in passing, had been the Grand Master of the Masonic Grand Lodge of Scotland since 1805. The building used at that time had been designed by the classical Greek revivalist architect William Playfair – and it looks more like (and indeed is based on the design of) a classical temple than an observatory. One Scottish Astronomer Royal based here was the clever but loopy Piazzi Smythe, whose book on the Great Pyramid includes a diagram showing how a meridian through that ancient monument divides the Nile Delta in half and meets the coast near the northern most part of the Delta arc.

Above: Playfair’s Edinburgh Observatory

The above painting by Alexander Nasmyth, painted in the year the observatory was granted royal status, shows the observatory in the centre, with Arthur’s Seat rising in the distance on the far right, beyond the castle.

As far as the Edinburgh observatory is concerned, we have not stepped outside of our understanding of the timing of these matters. But Roslin chapel with its extremely eccentric carvings and symbolism dates from earlier.

It was time to have a look at what was known about the history of Roslin, and to see if there were connections to Paris, and also to see how the concept of a meridian might have been of significance to its builders. I decided in addition that I wouldn’t be much of a researcher if I didn’t also look into whether the technical knowledge was available to whoever might have been responsible for plotting out this scheme, and to consider whether the Paris Meridian might have been older than its official inauguration by Louis the Sun King (given that Roslin is considerably earlier), or whether it was based on an earlier Scottish precedent.

First things first. I discovered that there were in fact many historical connections between Roslin and the French court in Paris. Roslin Chapel was founded by Sir William St Clair in 1446. This Sir William had in fact traveled himself to the royal court – located in the palace at the Louvre site in Paris – as ambassador and escort to the Scots Princess Margaret, who went on to marry the Dauphin (i.e. the heir to the French throne.) When he returned from France the earl set about a major building programme that included remodeling Roslin Castle in the French style. In addition, Sir William’s friend and tutor was Sir Gilbert Hay, a top scholar of the time who, after leaving St Andrew’s University in Scotland, went to France and lived in the royal court in Paris for twenty years, becoming the chamberlain of the future French king. When he returned to Scotland he lived at Roslin under the patronage of Sir William, and it was while he was living there that Roslin Chapel was built. These facts are given in the work of the Scottish historians Oxbrow and Robertson, Roslin and the Grail, which, despite the sound of its title, is based on historical documents rather than speculation, and makes no great sensationalist claims.

Exactly a century later, in 1546, queen Mary of Guise, consort of James V of Scotland, after visiting Roslin Chapel south of Edinburgh, wrote to its owner, another Sir William St Clair mentioning a secret that he had shown to her and promising not to reveal it. Sensing some great mystery, many have speculated about what it is that Roslin guards. Mary of Guise was herself of royal French stock, and while she was ruling as the regent of Scotland, the Florence-born Medici queen Catherine was made regent in France, ruling of course from the chief palace at the Louvre, where she had the builders start work on the Denon wing in 1560, the part that now houses works by Da Vinci and Michelangelo. At times during these periods Scotland and France were allies, and indeed Mary of Guise’ daughter married one of the sons of Catherine de Medici.

This of course raises some questions. While the Paris Meridian was laid out in the 1600s, by tying in Roslin we seem to be suggesting that in Scotland a meridian had already been lain out back in the mid fifteenth century. This is a bit of a mystery. Should we be connecting this to Freemason’s origins in Scotland, and to those origins being connected to guilds of master masons?

Could meridians have some Freemasonic connection? Within the Freemasonic Third Degree initiation there is an element of the rite which connects the Temple of Solomon with a north-south meridian. A certain Hiram Abif is struck at around noon by a man standing at the south gate with a plumb bob in his hand. There can be little doubt that a man standing due south holding a plumb bob was engaged in plotting out the North-South line, the Meridian, to align the temple. We should perhaps also bear in mind that in the Bible the building of the Temple of Solomon is linked to a great sword from heaven which extended across Jerusalem, reminding us surely of the French Meridian seen as the Sword.David looked up and saw the angel of the LORD standing between Earth and Heaven, and in his hand a drawn sword stretched out over Jerusalem.

David asks what should be done to rectify things, and he is commanded to go to a articular place to build an altar. He is inspired to build a great temple, but it is Solomon who actually builds it. It was then commanded that the “holy vessels of god” should be brought into the temple, along with the Ark of the Covenant. These “holy vessels” seem to connect to the idea of the Chalice / Holy Grail.

A similar mysteriousness seems to surround the Greenwhich Meridian. A connection to this English rose-line may perhaps be found in Shakepeare’s work. On the Internet a certain Paul Smith has put together a very useful list of dates that connect to the Et In Arcadia concept, and one of the entries reads:

Rosalind: “Well, this is the Forest of Arden”.

Touchstone: “Ay, now am I in Arden”.

William Shakespeare, As You Like It, II.iv.11-12.

It appears that an article appeared in the Shakespeare Quarterly of Washington in 1975 drawing attention to the similarity of the line ‘Now I am in Arden’ to the ‘Even in Arcadia I’ carved on Poussin’s tomb. Arden is similar to Eden, which is similar conceptually to Arcadia. It is surely also worth noting the similarity of Rosalind to ‘Rose-line’. The reason this is significant is that the Forest of Arden, which was once bigger than it is today, encompassed a region through which this English rose-line does indeed run. We might even note that on the Scottish rose-line Edinburgh seems once to have been called Eden Borough, according to Oxbrow and Robertson, and that the place where the Greenwich Meridian meets the south coast is in fact called Peacehaven, complete with its Greenwich House and Meridian Leisure Centre to mark the fact.

The Meridian passes close to Edenbridge on its way up towards Greenwich, reminding us again that Edinburgh in the Scottish scheme was once called Eden Borough, and of the forest of Arden on Rosalind’s Shugborough line. In the Middle Ages the floodplain south of Lewes was flooded, so that Lewes was effectively the place where the Meridian, if it had existed at that time, would have been located. I recently attended a workshop in Lewes given by Phillip Car-Gom, the head of the order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, a resident of Lewes, and he mentioned that Lewes was the site of the first Templar church in Britain, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (named after the church in Jerusalem most sacred to Christians) and he mentioned a little-known legend that this church in Lewes was the location of the Holy Grail. As the place where (in Templar times, since this was the meeting with the sea then) the point of the ‘V’ of the lower triangle, or ‘chalice’ of the Seal of Solomon would have been located, this Grail story is quite appropriate.

The Greenwich mystery looks more and more interesting as we look into it more deeply. The history goes back way before Charles II commissioned the observatory by Wren. The land came into the hands of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and Regent of England (effective king) in 1427, and he started building a palace by the river at Greenwich, named Bella Court. He was a learned humanist scholar who was in communication with the leaders of the new Italian humanism, had copies of Plato in his library and was a patron of scholars and men of letters, just as was William St Clair of Roslin in the same period. Humphrey was called ‘Good Duke Humphrey’ rather like the ‘Good King Rene’ of Anjou who was a champion of the Renaissance idea of Arcadia and also, like Humphrey, in contact with the movers and shakers of the early Renaissance, such as the Medici. In fact Rene is a clear link between Greenwich and Roslin. William St Clair is thought to have had direct links to Rene I of Anjou; they both appear to have been members of the royal knightly Order of the Golden Fleece, and certainly William commissioned his scholar Gilbert Hay to translate works by Rene. Greenwich too has its links to the House of Anjou. When Humphrey of Gloucester died in 1447 and the manor reverted to the Crown, Margaret of Anjou, a direct descendant of Rene, decided to adopt Bella Court as her place of residence. Margaret was the wife of the English King Henry VI. This year, 1447, was the year after William St Clair started building Roslin.

Margaret was the daughter of Rene of Naples, Duke of Anjou, King of Naples and Sicily and Isabella, Duchess of Lorraine. Roslin for its part would later be visited by Mary of Guise, also descended from the House of Anjou, who as we have seen, visited and wrote of a ‘secret’ there.

The palace at Greenwich was renamed Placentia, from the Spanish word meaning “Pleasant Place to Live”. It went on to be the principal royal palace for the next two centuries, during which time it was extensively rebuilt. Skipping over various royal connections, we come to the reigns of James I and Charles I during which time The Queen’s House, designed by Inigo Jones, was erected at the site, highly significant in British architectural history since it was the first classical building in England.

Then in 1660 Charles II, himself the grandson of the Louvre-born Marie de Medici, had Placentia rebuilt in the new classical style, and he founded the Royal Observatory there in 1675. The Royal Naval hospital was also built at the site as a place for retired seamen, another fine classical building built by Wren, and shown here as painted by Canaletto. Within it is the Painted Hall, a masterpiece of decoration said to be the finest dining hall in the Western world.

The French meridian goes, of course, through the capital city of Paris, and it also runs down through the city of Bourges that has long been held to be the centre of France, as well as through Amiens half way between Paris and the effective north point on the coast. Bourges and Amiens, like Paris, have great Gothic cathedrals. Bourges has an even older history of being an important spot, for it was Roman Avaricum, the capital of Aquitaine, and even before that, way back in the 7th century B.C., it was the centre of the Celtic Kingdom of the Biturges Cubi. There is a gold line that has been inserted in the floor of the cathedral of Bourges to show exactly where the Meridian runs. Might we be tempted to wonder whether, although the national hexagram shape was a later evolution, the idea of the median was older, and goes back to the time of the medieval master masons who built the great cathedrals?

When the French laid out the Paris Meridian in 1635, they did so believing that they were plotting out the longitude line exactly 20 degrees east of the ancient geographer Ptolemy’s Prime Meridian, which was defined as running through the western point of the Canary Islands (and actually they weren’t far wrong). Ptolemy’s Geography had been read for a long time in Europe by this point. In the late Dark Ages the classical writers were still being studied at the School of Chartres, in Northern France, around the time that Hugh Capet made Paris, formally a Roman city, the capital of France. Chartres’ statues include seven women representing the Liberal Arts and for each art there is also a statue of an ancient expert in that field, including one of Ptolemy, and since they were reading Ptolemy they must have come across the notion of longitude measured from a meridian, and would also have, most likely, attempted to work to Ptolemy’s longitude system, given that places in Gaul are mentioned in the Geography with latitude and longitude coordinates – including Bourges.

They also had the methods to plot out longitude. The chancellor of Chartres Cathedral in France, Fulbert, was, according to historian George Henderson in his book Chartres, the first man in Europe known to have used the astrolabe, an instrument that finds positions and altitudes of the stars, which he did from the top of one of the towers of the cathedral. Fulbert’s period was in the early eleventh century.

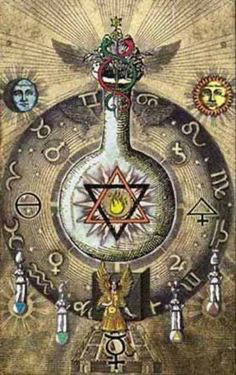

So then, a considerable amount of murky mystery hangs over this business. But what is clear is a national geodetic scheme based on the use of a geometric pattern, and one that could very easily generate a National Zodiac along the lines of the model described by Plato in his Laws, namely radiating from the centre of the country. A Zodiac around a hexagram is an image we find in alchemical texts, as for example in this Martinist image below:

And this second is from a seventeenth century work by Johann Daniel Mylius. Hexagram in the centre; Zodiac around the outside.

So there is some solid precedent for using the hexagram to generate a Zodiac wheel. But how to place the 12 signs within this?

The French Zodiac

Since our purpose here from the outset was to seek a resonant Hermetic landscape – as above, so believe – then we may recall that one of the most comprehensive types of this kind of landscape scheme is the twelve-sectored Zodiac. Plato in his Laws recommended a twelve-sectored scheme radiating from the centre of the country modeled on the revolving wheel of the heavens, and (no doubt influenced by this) Christianity adopted the idea, for the New Jerusalem that came down from the heavens with its twelve gates in Revelations is really such a scheme, and the twelve-sectored wheel is generated easily from the hexagram.

Clearly, the next step is to allow the Zodiac to sit upon the French hexagram. The question is how the Zodiac signs should be arranged within it. It’s time to look at Astraea. The Poussin Shepherds connection with the Pontils site far south along the Meridian creates the idea that that this area of Southern France is also Arcadia, an idea which is strengthened due to the way that the landscape becomes increasingly Mediterranean, classical, Arcadian as you go down south in France. Also, from Greece’s central sanctuary at Delphi, a meridian extending due South leads to the actual region of Arcadia, so this is a transposition of that arrangement onto the Paris Meridian. Arcadia in seventeenth century Europe became synonymous with the Golden Age. During the Golden Age, Astraea ruled the Earth. Astraea was the goddess of Justice. By saying she ruled, what was meant was that people were naturally ethical in their behaviour, so that that was no need for formalised systems of law. Now, Astraea was repeatedly and very firmly identified with the constellation of Virgo, even in Antiquity. The story was that when people became unethical, Astraea in horror left the Earth and ascended into the heavens, becoming the constellation of Virgo.

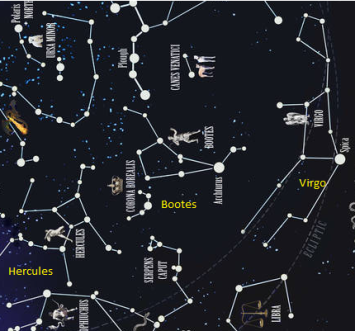

And Poussin showed Astraea in his Shepherds of Arcadia II. The painting has been interpreted extremely convincingly by Philip Coppens as containing a region of the constellations: Hercules, Bootes and Virgo. The Hercules constellation is a kneeling figure and Bootes (the ideal shepherd who like Daphnis was raised to the stars) is a figure who holds his staff in one had and has one foot raised up and resting on a rock, (that rock being identified slightly after Poussin’s time with Mons Mainalus in Arcadia.)

And Hercules, Bootes and Virgo stand next to each other in the sky:

So the standing female figure in Poussin’s painting is Astraea/Virgo, the goddess who rules Arcadia/the Golden Age.

It’s difficult not to ask: why did Poussin put these constellations in The Shepherds of Arcadia II? We can in fact arrive at an understanding that makes more sense out of this, and combines the theme of the restoration of the Golden Age / return of Justice (Astraea / Virgo) from Virgil’s fourth eclogue with that of the raising of the shepherd to the stars (as Bootes). To understand this, we need to recognise three things:

- Daphnis as described by Virgil in the fifth eclogue is a very direct parallel with the Greek figure of Ikarios

- The only resolution to the plague caused by the murder of Ikarios was for justice to be brought to the killers

- Ikarios was equated directly with Bootes

To explain: Virgil in the fourth eclogue describes Daphnis being mourned by those to whom he taught the celebration of Bacchic rites, and nature mourns him too, with the crops failing. Thus far the parallel with Ikarios is fairly exact. Dionysos taught Ikarios the art of winemaking, and Ikarios shared this gift with his countrymen – this parallels Daphnis teaching the Bacchic rites. However, a group of shepherds got drunk on the wine Ikarios had made, and believing themselves poisoned, killed Ikarios. Dionysos was angry at this, and inflicted a drought on the land. This parallels nature mourning the death of Daphnis. Dionysos then raised Ikarios to the stars as Bootes. This parallels Menalcas' Daphnis being raised as a god to the gate of heaven, bringing peace to all the countryside. The Athenians consulted an oracle on how to end the drought, and learned from this that they needed to honour Ikarios by instituting a festival in his honour. This parallels Mopsus in Virgil’s eclogue saying the shepherds must build a mound for Daphnis and carve an epitaph commending his fame and loveliness even to the stars, and also the shepherds at the end of the eclogue worshipping Daphnis in joyous rites. Bearing all this in mind there is no doubt that Daphnis is one and the same as Ikarios and that, therefore, where he is raised to the stars, it is as the constellation Bootes.

In light of this, the presence of Bootes in Poussin’s painting suddenly seems very appropriate, and we must conclude that it’s likely this was deliberate. And Virgo wears the golden mantle as goddess of the Golden Age, Astraea, because this was an illustration how much better things are when Justice is done.

While keeping this in mind, further insight into seventeenth century thinking on such matters can be gained by considering Ben Johnson’s masque The Golden Age Restored (1615). To quote Wikipedia:

The speeches were “presented” by the mythological figures standard in the masque form — in this case, Pallas Athena and Astraea were the primaries. Pallas banishes the personified Iron Age, thus allowing the return of Astraea, goddess of Justice, and the restoration of the Golden Age. A major theme of Jonson’s text was the reform of a corrupt court — relevant at the time because the Stuart Court was suffering the aftermath of the scandal over the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury.

Quite possibly Virgil too had a particular person in mind, and in his eclogue it seems the injustice may simply be that the greatness of a poet has not being recognised, and ought to be. In other words Daphnis is functioning as an allegory for a real poet whose greatness should be sung. From the other eclogues, it seems highly likely this was Gallus. Indeed, the tenth eclogue is modeled on Theocritus’ eclogue on the death of Daphnis from a broken heart, but with Daphnis replaced by Gallus. Gallus is described as being in Arcadia, and again, even nature is weeping on behalf of him. A series of gods come, one by one, to try to ease his broken heart. So Virgil himself is seeking to end the injustice by composing eclogues honouring this poet. The tomb in Arcadia in Poussin’s painting thus with some justification conflates the fifth eclogue (the tomb with the epitaph, but in Sicily, not Arcadia) with the tenth eclogue (the death in Arcadia), while also bringing in the fourth eclogue (the return of Astraea and the Golden Age) based on Daphnis being an allegory for Gallus – the dead poet who should be recognised, if justice is to be done.

Interestingly, any connection here to the Meridian is derived from the polar opposite of the memento mori. Rather than mortal achievements being nothing but vanity, they are something that must be recognised, the memory of them passed on. Daphnis’ fame extends “even to the stars” and he is raised to Heaven’s Gate – i.e. the constellation reaches its highest point, at the Meridian, due south – an apotheosis.

But back to the plot. This has given us a start for the French Zodiac – Virgo is placed at the most southerly position (in the region of the Pontils/Poussin tomb, which put Pisces in the northern spot. But the next question is whether the Zodiac should be a mirror image or a copy of the wheel of the sky. Either you let the sky simply reflect down on the ground, or you take the image from the sky as it is and a duplicate it on the ground. If you reflect it onto the ground, you’ll get Leo to the left of Virgo, and Libra to the right, whereas what you actually see looking into the sky has Leo to the right of Virgo, and Libra to the left. We can actually allow a bit of serendipity to answer this for us. In the region to the right of that we have assigned to Virgo is the Golfe du Lion, the Gulf of the Lion.

It is not known why the gulf is named after a lion – one theory is that the sea here is fierce like a lion, but this is very much just a theory – but whatever the origin, it allows us to put Leo to the right of Virgo. I have another reason for liking this arrangement – it puts the Lion Mountain of Sainte Victoire near Aix within the Leo sector – but I won’t go into that just yet.

So there it is, the most resonant, Hermetic, Platonic landscape scheme that can be salvaged out of the Rennes-le-Chateau business.

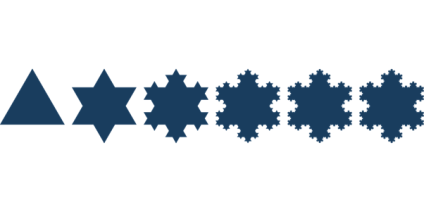

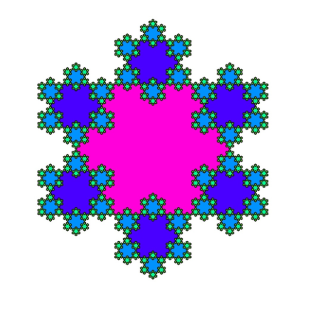

It’s a scheme which can actually be developed further. Plato in his Laws described the radiation of the twelve sectors from the centre of the nation, but then said there should be further iterative divisions into twelve within each of the twelve sectors. Since we’re starting here with the hexagram, the pattern that comes to mind is the Koch Snowflake. This is a fractal pattern which takes the elemental procedure that turns a simple triangle into a hexagram, and then repeats it. The image below shows five iterations.

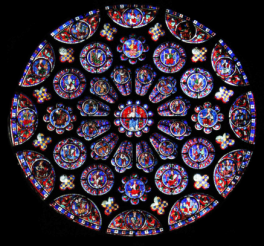

And the image here below shows it in the form of hexagrams set within hexagrams. This suggests a way to create further zodiacs within the main Zodiac, in a manner that is reminiscent of French cathedral stained glass rose window patterns, such as the twelve-sectored one shown here, from Chartres.

Now, while Paris is halfway between the centre of the hexagram and French North Point, at the top of the Meridian, Amiens is close to halfway between Paris and North Point, and the cathedral there is decorated with carvings of the Zodiac signs. This inspires the idea of a Sub-Zodiac centred on Amiens, derived from the Koch Snowflake, as shown here below along with further sub-zodiacs in the equivalent positions around the hexagram.

The Rennes-le-Chateau mystery would have us pulled down a rabbit hole, literal and metaphorical. Literal – there’s the story about a shepherd Ignacio Paris who in the seventeenth century followed a sheep that fell down a hole, only to find some amazing treasure, but here as elsewhere there is doubt about whether this is an old story or one invented in the 1950’s. And no doubt if one was to look into it, it would throw up some further line of inquiry to investigate and so it goes on – pulling us deeper down the rabbit hole.

There comes a time to pull oneself out again. The Et In Arcadia motto no doubt has various levels of meaning – and has meant different things at different times to different people – but the one that seems to me to be the most obvious is also one of the most interesting. “I also in Arcadia,” while worded like the opening of the kind of statement from beyond the grave you’d find on a classical tomb, also presupposes that the individual is also an Arcadian, and as such this is about a change of identity through a blurring of the boundaries between the mundane modern world and an idealised, archetypal, classical Golden Age, a kind of Platonic Idea of antiquity, and a utopian otherworld. The implicit assumption is “I, too, am an Arcadian.” As a motto it is then both a statement of artistic intention – to avoid the excesses of baroque and rococo and mannerism and return to a purer, classical, rustic simplicity – and also a statement of a new identity, which is to say a conception of oneself as having been transformed by the likes of the Grand Tour and exposure to classical art and architecture and through this transformation becoming included on some level within a group that stretches back through the ages, in other words having been initiated into the mysteries of the Arcadian Dreamtime. If we look at the Arcadian Academy of Rome, we may therefore say that where this group of poets envisioned themselves as Arcadian shepherds exchanging rustic lays like those in Virgil’s eclogues, at some level the real motivation here is not so much a manifesto aiming at purifying Italian poetry, as it is to expand identity and indeed consciousness by establishing a morphic resonance with an ancient idea.

So when I consider the riddle that is thought to be located in the letters beneath the Shugborough Hall Shepherds of Arcadia relief, I favour a simple interpretation.

The D and M at the sides are accounted for, as an imitation of ancient Roman tombstones where it commonly stood for Dis Manibus – “to the shades” or “to the ancestral spirits”. The rest is, like the relief itself, horizontally reflected. And the V.V is W, and the other V is the Greek lower case “n”: ν. And the U is vertically reflected. That gives

W ANSON O

A simple memorial to William Anson, the first owner of Shugborough Hall. Why the “O” on the end? With the U inverted, this makes the last four letters “sono” – Italian for “I am”. The whole meaning is then “I am W Anson. Even in Arcadia, I”. Or rather:

I, W Anson, am also in Arcadia.

William’s son Thomas, who inherited the house, was the founder of the Society of Dilettanti in 1732, established for the appreciation of classical Greek art, just as in Rome the Arcadian Academy evolved form a group of poets to a society with a more general interest in the classical tradition.