The symbolism of Le Serpent Rouge...

Le Serpent Rouge is a short, mysterious text first published in Paris in 1967.

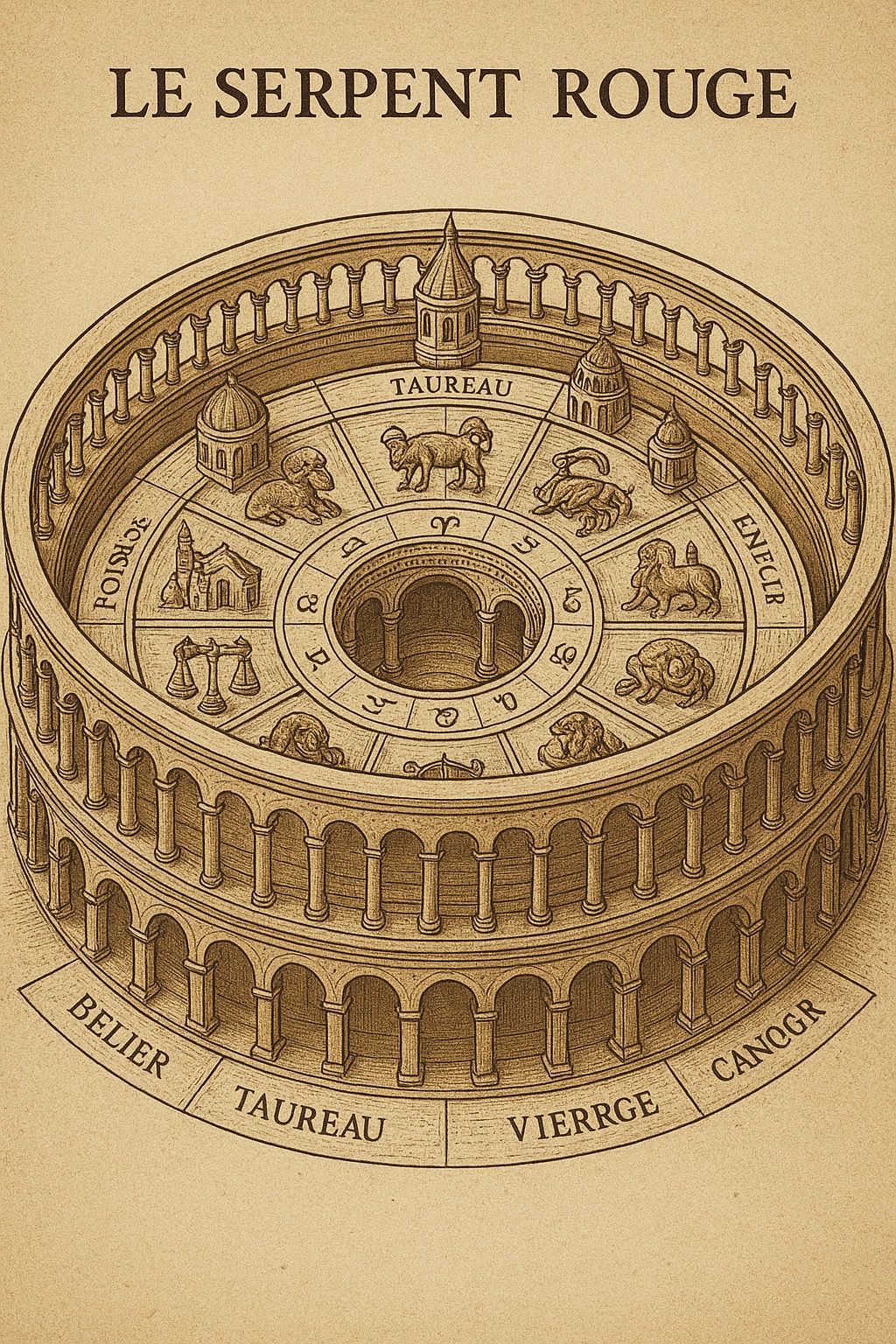

- It is a pamphlet/poem, about 13 short sections, each styled after a zodiac sign (Aquarius through to Capricorn, plus the 13th sign Ophiuchus/Serpent).

- It was first published in Paris on 17 January 1967, with a small print run.

- The style is esoteric, allegorical, and visionary: it blends Biblical imagery, pagan myth, alchemy, sacred geometry, landscape references, and coded allusions to Rennes-les-Bains/Rennes-le-Château.

- Attributed to three men: Pierre Feugère, Louis Saint-Maxent, and Gaston de Koker.

- Curiously, all three died suddenly around the time of its deposit/publication (some say suicides). This “coincidence” gave the text a reputation for being cursed or dangerous.

- The sequence of poems as a cryptogram point to a sacred landscape zodiac (a “terrestrial horoscope” drawn onto the map of the region, with mountains, rivers, and churches marking zodiac signs).

- The imagery & symbolism include Frequent references to the Magdalene, Blanche of Castile, ancient goddesses, alchemical transformations, and landscapes of the Languedoc.

- The context & theories are;

- Pierre Plantard & Philippe de Chérisey:

Most researchers believe Le Serpent Rouge was concocted by them (or their circle) as part of the broader Priory of Sion mythos. De Chérisey, in particular, was fond of riddling texts full of wordplay, anagrams, and esoteric allusions. - Esoteric map:

Some read the sequence of poems as a cryptogram pointing to a sacred landscape zodiac (a “terrestrial horoscope” drawn onto the map of the region, with mountains, rivers, and churches marking zodiac signs). - Gnostic/alchemical meditation:

Others treat it less as a treasure map and more as a spiritual allegory – the “Red Serpent” as Kundalini, the descent into shadow, or the dragon guarding the treasure of wisdom. - Deaths of the three “authors”:

The fact that Saint-Maxent, Feugère, and de Koker all died suddenly in late 1966 (within a month of each other) adds to its aura of mystery. The implication may have been: “these men died for revealing secrets.

- Pierre Plantard & Philippe de Chérisey:

Though short, Le Serpent Rouge has become:

- A keystone text in Rennes-le-Château research.

- An example of modern myth-making, blending surrealist poetry with esoteric codes.

- A cultural oddity – part hoax, part artwork, part spiritual meditation.

Lets unpack it sign by sign (Aquarius → Pisces + the Serpent), showing the meaning and possible landscape link for each. That’s often where the hidden structure reveals itself.

Part I: The Textual Framework

1 The Zodiacal Structure

The architecture of Le Serpent Rouge is explicitly zodiacal. The text comprises twelve poems, each aligned with a sign of the zodiac, beginning with Aquarius and ending with Capricorn, followed by a thirteenth poem titled Ophiuchus which is the Serpent. This framework situates the text within a long tradition of associating initiatory journeys with cosmological cycles. Astrology has historically functioned as more than a predictive tool; it was regarded as a symbolic language that mapped the human soul onto the structure of the heavens. In hermetic philosophy, “as above, so below” (from the Tabula Smaragdina) implied that the zodiac reflected stages of inner transformation as much as the motion of the stars.¹ Thus, a cycle through the zodiac could represent a cycle of the initiate’s spiritual progress.

The choice to begin with Aquarius is notable. In astrological symbolism, Aquarius is associated with revelation, water, and purification — motifs central to baptism and renewal. Ending with Capricorn, traditionally the sign of endurance, trials, and rebirth, suggests a closing in difficulty but also an anticipation of transcendence.² The final, thirteenth passage, “Serpent,” cannot be overlooked. In numerological terms, twelve signifies order (the signs of the zodiac, months, apostles, tribes of Israel), while thirteen breaks or transcends that order, often associated with transformation, death, or initiation.³ The serpent thus embodies the paradox of danger and renewal, echoing its dual role in biblical and alchemical traditions.

2. The Zodiac and the Pilgrimage Motif

The zodiacal cycle in Le Serpent Rouge does not function as a horoscope but as a coded pilgrimage narrative. Each poem presents the reader with an allegorical trial:

- Aries speaks of cutting through an “inextricable forest” with a sword in search of the “Sleeping Beauty,” a fairy-tale figure here elevated into an allegory of the Queen of Wisdom or the Grail.

- Gemini instructs the seeker to gather scattered stones and reorder them “with compass and square,” a clear allusion to masonic practice.

- Libra culminates with the seeker gazing from the window of a ruined house toward a radiant cross on the mountain crest, symbolising illumination.

These episodes echo the medieval tradition of the spiritual pilgrimage, wherein the journey was less geographic than moral and symbolic. Texts such as Guillaume de Deguileville’s Pèlerinage de l’Âme [Pilgrimage of the Soul] (14th century) depicted allegorical travels towards salvation through landscapes of trial.⁴ In Le Serpent Rouge, the zodiacal framework provides the scaffolding for a similar spiritual progression: the initiate wanders, becomes lost, receives guidance, and at last confronts the guardian serpent.

The invocation of Ariadne’s thread in Aries further underlines the initiatory nature of this pilgrimage. Ariadne’s thread in classical mythology guided Theseus through the labyrinth; in Christian allegory, it often symbolised grace or wisdom leading the soul through confusion.⁵ By invoking Ariadne, the text acknowledges that the seeker requires both external guidance and inner discernment to navigate the labyrinthine mysteries of the Rennes landscape and it’s mystery..

3. Stylistic Features: Surrealism and Liturgy

A key element in the puzzle of Le Serpent Rouge is its stylistic hybridity [Hybridity describes the process of combining or mixing distinct elements to create something new, a concept originating in biology but now applied across many fields like culture, linguistics, and identity]. Scholars and commentators have noted that the poems combine three dominant registers:

- Biblical cadence [Cadence means "the rhythm of sounds" from its root cadere which means "to fall." Originally designating falling tones especially at the end of lines of music or poetry, cadence broadened to mean the rhythms of the tones and sometimes even the rhythm of sounds in general]. The rhythm of the prose in the poem often recalls the Vulgate Bible and liturgical prayer. For instance, in Cancer the pilgrim sees mysterious symbols carved on black and white stones and recalls the vision of Constantine: “Par ce signe tu le vaincras” (In hoc signo vinces). This scriptural resonance lends the text an aura of sacred authority.⁶

- Mythological surrealism. Certain passages employ imagery reminiscent of French surrealism. Scorpio, for example, describes a monstrous octopus-like spiral darkening the mind, imagery that echoes André Breton’s dreamscapes.⁷ Such language situates the text not only within esoteric traditions but also within 20th-century literary currents that blurred the boundaries between dream, myth, and reality.

- Esoteric riddling. The poems are saturated with cryptic references, such as the “sixty-four stones of the perfect cube” in Taurus. The number 64 resonates with both masonic symbolism (squares upon squares) and the hexagrams of the I Ching.⁸ By refusing to explain such allusions, the text positions itself as a riddle-book — accessible only to initiates, or those willing to engage in hermeneutic labour.

This stylistic hybridity is likely intentional. By weaving together biblical gravitas, surrealist imagery, and cryptographic density, the author(s) constructed a text that functions simultaneously as liturgy, dream, and puzzle.

4. The Role of the Thirteenth Passage: Ophiuchus/Serpent

The concluding passage, Ophiuchus/Serpent, is both culmination and key. Here, the voice of the initiate (or narrator) declares knowledge of the “seal of Solomon” and warns the reader not to “add or subtract a single iota” from the words — an unmistakable echo of Revelation 22:18–19, which condemns altering scripture. In Jewish and esoteric traditions, the seal of Solomon (hexagram or interlaced triangles) represents mastery of hidden wisdom, dominion over spirits, and the unity of opposites.⁹ To claim this knowledge is to assert initiatory authority. Yet the serpent also carries biblical connotations of temptation and danger: the guardian of Eden’s tree of knowledge.

Thus, the thirteenth passage functions as a threshold. The serpent is both guardian and revealer, warning against hubris even as it proclaims possession of the secret. Its numerical position (beyond the twelve) marks it as the element of transcendence, the completion of the cycle. In alchemical symbolism, this recalls the ouroboros, the serpent that devours its own tail, symbol of eternal renewal.¹⁰

The paradox embodied in Ophiuchus/Serpent epitomises the nature of Le Serpent Rouge as a whole: both warning and invitation, both scripture and riddle, both myth and geography.

Notes

- Liz Greene, The Astrology of Fate(London: Weiser, 1984), pp. 112–118.

- Corpus Hermeticum, ed. A.D. Nock & A.-J. Festugière (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1946).

- Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1954), pp. 34–35.

- Guillaume de Deguileville, Le Pèlerinage de l’Âme, ed. A. J. Minnis (Oxford: Clarendon, 1984).

- Jean Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1953), pp. 82–84.

- Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 44, on Constantine’s vision.

- André Breton, Manifestes du surréalisme (Paris: Gallimard, 1924).

- Richard Wilhelm, The I Ching or Book of Changes, trans. C.F. Baynes (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1950).

- Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), pp. 134–136.

- Carl Gustav Jung, Psychology and Alchemy (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1968), pp. 146–150.

Part II: Symbolic Landscapes

3. The Geography of Rennes-les-Bains

At the heart of interpretations of Le Serpent Rouge lies the question of geography. Unlike purely visionary texts, the poems are saturated with references to specific stones, mountains, churches, and rivers. These are not abstract symbols but identifiable features of the Languedoc landscape, particularly around Rennes-les-Bains, Rennes-le-Château, and the Blanchefort ridge.

For example:

- Pisces describes the “roc blanc” (white rock) and “roc noir” (black rock), which commentators identify with contrasting geological features near Cardou and Blanchefort.¹

- Taurus mentions “soixante-quatre pierres dispersées du cube parfait,” linked by some to scattered megaliths or stone markers in the Rennes valley.²

- Libra culminates with the sighting of a large cross on a ridge, which may correspond to the Croix de Cardou or to the 35 cm summit cross referenced in local lore.³

These passages suggest that the author(s) of Le Serpent Rouge were intimately familiar with the topography of Rennes-les-Bains and projected their esoteric narrative onto its terrain. In this sense, the poems form a literary map, guiding the reader not only through spiritual stages but across a mythologised geography.

4. Geomantic and Templar Traditions

The notion that landscapes encode sacred diagrams is not unique to Rennes. Medieval geomancy, pilgrimage cartography, and later esoteric speculation frequently reimagined natural features as symbols in stone.

- In the Middle Ages, churches were often aligned to solstices, equinoxes, or stellar risings.⁴

- Templar architecture has long been associated, rightly or wrongly, with “hidden geometries” connecting commanderies.⁵

- In early modern hermeticism, mountains, rivers, and stones were read as “signatures” of the divine, inscribed in creation for those with eyes to see.⁶

Within this tradition, Le Serpent Rouge can be read as a geomantic palimpsest, where the Rennes valley becomes a kind of terrestrial zodiac. Just as Glastonbury was reimagined by Katherine Maltwood in the 1930s as a vast “terrestrial zodiac” mapped onto the Somerset countryside, Rennes appears in the poems as a sacred diagram etched in hills, stones, and ruins.⁷

The frequent references to white and black stones, to crosses, and to orientations (east to west, north to south) strongly imply a ritualised landscape. This is consistent with masonic and templar traditions, in which land itself could serve as the temple, with natural features taking the place of architectural elements.

5. Comparative Cases

The Rennes zodiac is not an isolated phenomenon but part of a broader esoteric practice of mapping cosmology onto territory:

- Glastonbury Zodiac (Somerset, UK). In 1935, artist Katherine Maltwood argued that giant zodiacal effigies were inscribed in the Somerset landscape, formed by hills, rivers, and roads.⁸ Though archaeologically dubious, the idea became influential in British esoteric circles.

- Chartres Cathedral Labyrinth. Pilgrims walking the labyrinth were symbolically traversing the cosmos; some scholars argue its geometry mirrors stellar patterns.⁹

- Pilgrimage routes. The Camino de Santiago has been interpreted not only as a path to Compostela but as a terrestrial echo of the Milky Way.¹⁰

By comparison, the Rennes landscape in Le Serpent Rouge functions as a sacred mandala, where the initiate’s journey through zodiacal verses mirrors a physical journey across stones, ruins, and mountains. This hermeneutic interplay between text and territory is a hallmark of esoteric literature, where geography becomes theology.

6. Sacred Topography and the Hidden Temple

Several poems explicitly describe the land as if it were a temple-in-ruins:

- In Gemini, the seeker works with compass and square to reorder scattered stones, suggesting the rebuilding of Solomon’s temple in miniature.

- In Cancer, the pilgrim sees the black-and-white tiled floor — a masonic mosaic pavement projected not into a lodge but into the earth itself.

- In Scorpio, the initiate stands in the sanctuary and pivots from the rose of “P” to that of “S,” describing an orientation within a sacred architectural space, even as it maps onto the Rennes church itself.

These elements suggest that Le Serpent Rouge is staging the Rennes landscape as a New Jerusalem, a terrestrial Solomon’s Temple hidden in valleys and rocks. The allusion to the “new temple of Solomon” in Scorpio confirms this interpretive key.¹¹

The Rennes topography, then, is not accidental background but the central “text” to be deciphered. The poems guide the initiate in reading the land as scripture, a hierophany of stone.

Notes

- Bill Putnam and John Edwin Wood, The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château: A Mystery Solved (Sutton, 2003), pp. 84–86.

- Paul Smith, The Priory of Sion Hoax (2005), pp. 144–147.

- André Douzet, Le Secret des Cathares (Perpignan: Bélisane, 1989).

- J. K. Wright, The Geographical Lore of the Time of the Crusades (New York: AMS Press, 1965).

- Malcolm Barber, The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple (Cambridge: CUP, 1994).

- Paracelsus, De Natura Rerum (1537), trans. A. Weeks (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

- Katherine Maltwood, A Guide to Glastonbury’s Temple of the Stars (London: The Women’s Printing Society, 1935).

- Ibid.

- John James, The Contractors of Chartres (London: West Grinstead, 1990).

- Edwin Mullins, The Pilgrimage to Santiago (London: Constable, 1974).

- Gérard de Sède, L’Or de Rennes (Paris: Julliard, 1967), pp. 244–246.

Part III: Myth, Bible, and Tradition

7. The Classical Tradition: Ariadne, Hercules, and the Labyrinth

The mythological allusions in Le Serpent Rouge are not decorative but structural. In Aries, the pilgrim seeks the “Sleeping Beauty” and follows the “fil d’Ariane.” This recalls the myth of Theseus, who penetrates the labyrinth of Crete with Ariadne’s thread, a paradigm of guidance through peril.¹

In Cancer, the pilgrim laments that he is not Hercules, who possessed magical strength to overcome monsters. Hercules represents both brute force and divine assistance — a reminder that the pilgrim lacks sufficient power and must rely instead on knowledge and faith. Taken together, these references frame the initiate’s journey as a labyrinthine trial: the seeker wanders through forests and ruins as if through a symbolic maze, guided only by fragments of text (“les parchemins de cet Ami furent pour moi le fil d’Ariane”). This intertwines the fairy-tale motif of the lost path with the initiatory ordeal of classical myth.

8. The Biblical and Apocryphal Layer

Interwoven with classical myth are explicit biblical allusions:

- In Cancer, the pilgrim recalls Constantine’s vision, “Par ce signe tu le vaincras,” directly echoing Eusebius’s Life of Constantine (I.28).²

- In Leo, the desired woman is named Isis by some, Magdalene by others, but the pilgrim recalls Christ’s words in Matthew 11:28: “Come to me, all you who labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

- In Virgo, the motto “Retire moi de la boue, que je n’y reste pas enfoncé” echoes Psalm 69:15, a plea for divine rescue.

These biblical resonances are not randomly chosen but consistently eschatological and salvific. The seeker is not simply wandering: he is reenacting the biblical drama of fall and redemption, darkness and light, exile and homecoming.

The tension between Jesus and Asmodeus (the demon said to inhabit the church of Rennes-le-Château) dramatises the duality of the landscape: sacred ground haunted by fallen powers. By juxtaposing Christ and the demon, the text underscores that the pilgrim walks a contested space, where every sign has both divine and infernal dimensions.

9. The Feminine Archetype: Isis, Magdalene, Notre-Dame

Central to the text is the mysterious feminine figure, variously named:

- Sleeping Beauty in Aries — an allegorical maiden, inaccessible without the key of wisdom.

- Isis in Leo — the Egyptian goddess of healing and resurrection.

- Madeleine in Leo — the biblical Mary Magdalene, penitent yet bearer of healing balm.

- Notre-Dame des Cross — the hidden, true name given only to initiates.

This polymorphic feminine archetype links pagan goddess, Christian saint, and Marian devotion into a single figure. She represents the secret of the land itself: a veiled Sophia, wisdom hidden beneath layers of myth.The Magdalene is particularly significant in the context of Rennes, where local tradition has long associated the region with her presence after the Resurrection.³ In identifying the sought-for lady with Magdalene, the poem binds together landscape, scripture, and local legend into one initiatory myth.

10. The Esoteric Hermeneutic: Double Reading

Throughout Le Serpent Rouge, references are constructed with deliberate ambiguity, allowing multiple simultaneous readings:

- Ariadne’s thread: both a literal guidance motif and a reference to textual exegesis, where the parchment itself becomes the thread.

- Sleeping Beauty: both a fairy-tale princess and the Sophia/Notre-Dame of gnosis.

- Isis/Magdalene: both pagan goddess and Christian saint, revealing continuity between ancient and Christian mysteries.

- Black and white stones: both geological features and masonic symbols of duality.

This double hermeneutic — literal and allegorical, geographical and spiritual — is characteristic of esoteric traditions. Medieval exegetes employed the quadriga (which means literal, allegorical, moral, anagogical readings, where anagogical is a method of spiritual interpretation that seeks to reveal the higher, mystical meaning of a text, particularly scriptures, and relates it to the afterlife or heavenly realities. It is considered the highest of the four traditional senses of scriptural interpretation, which also include literal, allegorical, and moral senses. The term comes from the Greek word anagoge, meaning "elevation" or "ascent," reflecting its purpose to "lead up" or "lift up" the reader to spiritual truths), while Renaissance hermeticists insisted on reading the Book of Nature alongside scripture. Le Serpent Rouge belongs to this lineage: a text demanding that the reader oscillate between the visible landscape and the invisible meaning.

11. Myth and Apocalypse: Toward the Serpent

The mythological and biblical threads converge in the final passages. In Scorpio, the pilgrim experiences vertigo, spiralling into darkness as if swallowed by Leviathan. In Sagittarius, the Serpent Rouge itself is revealed, a cosmic monster unfurling its coils like an apocalyptic beast from Revelation 12. The serpent thus functions as both culmination of myth (ouroboric cycle, guardian of wisdom) and fulfillment of prophecy (apocalyptic dragon). It is both Ariadne’s labyrinth and John’s Revelation, both Isis’s secret and Magdalene’s tomb. In this fusion, the Rennes landscape becomes not just mythologised geography but an apocalyptic stage, where myth and scripture enact the eternal drama of good and evil, concealment and revelation.

Notes

- Eusebius, Life of Constantine, trans. Averil Cameron & Stuart Hall (Oxford: Clarendon, 1999).

Plutarch, Theseus, in Lives, trans. B. Perrin (Loeb Classical Library, 1914).

- Jean Markale, Légendes de la Marie-Madeleine (Paris: Pygmalion, 1983).

- Mircea Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion (London: Sheed & Ward, 1958).

Part IV: The Serpent and the Secret Tradition

12. The Serpent as Esoteric Symbol

The serpent is among the most polyvalent symbols [that is, having or using a lot of different forms or features] in religious history. In Le Serpent Rouge, it appears explicitly in the thirteenth passage (Ophiuchus/Serpent) and implicitly in several zodiac verses. Its resonances include:

- Biblical duality: the tempter of Eden (Genesis 3) versus the brazen serpent raised by Moses for healing (Numbers 21:9).

- Hermetic wisdom: the ouroboros, serpent biting its tail, representing eternity and cyclical regeneration.¹

- Apocalyptic conflict: the great red dragon of Revelation 12, cast down from heaven by Michael.

- Initiatory guardianship: in mystery traditions, the serpent guards hidden treasure, accessible only to the worthy.

In this sense, the Serpent Rouge is not merely a monster but the very embodiment of threshold knowledge: it both obstructs and reveals. The pilgrim must confront the serpent not to destroy it but to integrate its wisdom.

13. Freemasonry and the Temple of Solomon

Several passages allude unmistakably to masonic symbolism:

- Gemini: “œuvrer de l’équerre et du compas” — the fundamental working tools of the mason.

- Cancer: the black-and-white tiled pavement, the mosaic floor of every lodge.

- Scorpio: the “new temple of Solomon” built by “the children of Saint Vincent,” suggesting a continuation of Solomon’s temple-building tradition.

The invocation of Solomon is central. In biblical and masonic traditions alike, Solomon’s Temple is not only a historical building but the archetype of cosmic order. To rebuild the Temple is to restore harmony between heaven and earth. By placing the initiate within a landscape-temple, Le Serpent Rouge merges geography with architecture, nature with ritual space. The Rennes valley is reimagined as a masonic temple writ large, where mountains become pillars, rivers become pavements, and churches serve as sanctuaries.

14. The Priory of Sion and Modern Esoteric Mythmaking

The historical background of Le Serpent Rouge cannot be separated from its emergence in the 1960s within the milieu of the Priory of Sion hoax.² Gérard de Sède’s L’Or de Rennes (1967) incorporated elements of the Rennes-le-Château mystery and amplified them with fabricated documents (the “Dossiers Secrets”). Scholars now recognise Le Serpent Rouge as part of this constellation, possibly authored by Pierre Plantard or his associates.³ Yet its literary quality and density of symbolism exceed mere pastiche. The text draws authentically on esoteric traditions — biblical, hermetic, masonic — while embedding them in the Rennes landscape. In essence it is mimicking that extraordinary work, CIRCUIT, by Philippe de Chérisey, long time friend of Pierre Plantard. In this sense, Le Serpent Rouge exemplifies modern esoteric mythopoesis: the conscious construction of myth that blurs history and fiction, fact and initiation. Whether as hoax or revelation, its symbolic framework resonates with genuine currents of Western esotericism.

15. The Serpent as Custodian of the Secret

The serpent in the thirteenth passage declares:“Voici la preuve que du sceau de SALOMON je connais le secret…” The Seal of Solomon, or hexagram, is traditionally a talisman of wisdom and protection, associated in medieval grimoires with the control of spirits.⁴ Its invocation here signals that the ultimate “secret” of the Rennes mystery is not treasure in a material sense but hidden knowledge. The serpent, then, is custodian of this secret. It warns the reader not to “add or subtract an iota,” echoing Revelation’s final warning against corrupting sacred text. The pilgrim, having traversed the zodiacal cycle, must finally confront the serpent’s paradox: the secret can be known only through fidelity, humility, and silence. Thus, the text culminates not in possession of treasure but in a moral injunction: guard the secret, meditate, and do not profane.

16. Tradition, Transmission, and Transformation

Finally, Le Serpent Rouge reveals its place within the broader Western esoteric tradition:

- Like alchemical texts, it encodes wisdom in symbolic and cryptic language.

- Like mystical pilgrim narratives, it stages the soul’s journey as an ascent through trials.

- Like masonic ritual, it projects the temple into landscape and cosmos.

- Like apocalyptic prophecy, it ends with confrontation with the serpent, the ultimate test.

At the same time, the text is modern, deliberately ambiguous in authorship and context, reflecting 20th-century currents of surrealism, mythopoesis, and conspiracy. It stands at the threshold between tradition and invention, at once heir to esoteric lineage and artifact of esoteric imagination.

Notes

- Ioan P. Couliano, The Tree of Gnosis (Cambridge: CUP, 1992), pp. 44–46.

- Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince, The Templar Revelation (New York: Touchstone, 1998), pp. 72–75.

- Paul Smith, Priory of Sion Hoax (2005), ch. 4.

- Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), pp. 363–365.

Part V: Conclusion — The Meaning of Le Serpent Rouge

17. The Zodiac as Initiatory Cycle

At its structural level, Le Serpent Rouge presents a zodiacal journey. Each of the twelve signs embodies a symbolic stage: from the revelation of Aquarius to the trials of Capricorn. The thirteenth passage (Serpent) completes the cycle, not by resolving it but by transcending it. The zodiac thus frames the text as an initiatory itinerary, in which the seeker confronts trials, temptations, and mysteries on the path to gnosis. This structure places Le Serpent Rouge in continuity with Western initiatory literature: the pilgrim’s progress of Bunyan, the labyrinthine trial of Ariadne, the allegorical ascent of Dante. Its difference lies in the deliberate fusion of myth, Bible, and geography into a single esoteric tapestry.

18. The Rennes Landscape as Temple and Mandala

The Rennes valley is not a backdrop but a protagonist in the text. Hills, stones, crosses, and ruins are transfigured into elements of a vast cosmic temple:

- White and black rocks [Blanchefort/Roc Negre] = duality of the mosaic pavement.

- Scattered stones = the building blocks of the cube, the perfect order. The clue of the chessboard in decipherment.

- Crosses on ridges = stations of ascent, culminating in the thirteenth cross.

- Springs and rivers = baptismal sources of renewal.

In this way, the landscape becomes a mandala, a sacred diagram upon which the initiate projects the zodiacal cycle. To traverse the land is to traverse the cosmos; to rebuild its stones is to restore Solomon’s temple; to read its signs is to enter revelation.

19. Myth, Bible, and the Feminine Secret

At the heart of the poems lies the figure of the hidden lady: Sleeping Beauty, Isis, Magdalene, Notre-Dame. She is the Sophia of gnostic tradition, the veiled wisdom of the earth, the treasure sought by knights and poets alike.The initiate’s goal is not treasure of gold but reunion with this feminine archetype — the embodiment of gnosis, healing, and resurrection. Her polymorphic identity reveals the continuity of tradition: pagan, biblical, medieval, and modern all collapse into her singular presence. Thus, Le Serpent Rouge encodes a mystery of the feminine divine, a theme long associated with Rennes-le-Château and its Magdalene devotion.

20. The Serpent and the Custody of Knowledge

The serpent, final guardian, dramatises the paradox of esoteric wisdom. It is both destroyer and healer, tempter and revealer, guardian and initiator. To confront the serpent is to face the ultimate ambivalence of knowledge: that it can save or damn, depending on how it is received. By invoking the Seal of Solomon, the serpent identifies itself with custody of hidden wisdom. It demands that the reader neither profane nor distort the secret. The text closes, therefore, not with revelation but with warning: the treasure exists, but it is protected; knowledge is accessible, but only through reverence.

21. Historical Position: Hoax, Tradition, or Both?

Historically, Le Serpent Rouge emerged in the 1960s, in proximity to the Priory of Sion forgeries. Scholars agree that its immediate origin is modern, perhaps even a hoax. Yet its symbolic density cannot be dismissed. Like all effective myths, it fuses invention with authentic tradition.Whether penned by mystics, hoaxers, or both, the text succeeds because it replays ancient patterns: the zodiacal cycle, the sacred landscape, the archetypal feminine, the apocalyptic serpent. It is therefore both a modern fabrication and a genuine expression of Western esotericism’s perennial symbols.

22. Final Synthesis

What, then, is the meaning of Le Serpent Rouge? It is a mandala-text, where time (zodiac), space (Rennes landscape), and myth (Bible, classics, esotericism) converge. It invites the reader to undertake a pilgrimage — geographical, symbolic, and spiritual — through twelve stages of trial and a final confrontation with the serpent.

It is a mirror of tradition, where Isis and Magdalene, Solomon and Asmodeus, Hercules and Christ coexist. It encodes the perennial esoteric conviction that the divine is hidden in plain sight, inscribed in nature, scripture, and myth.

It is, finally, a modern myth, born in an age of hoaxes and conspiracies, yet capable of evoking the eternal. In its ambiguity — poem or code, revelation or forgery — lies its enduring power. For the initiate, the meaning is not to solve but to journey; not to seize but to contemplate.

Epilogue

The pilgrim who reads Le Serpent Rouge does not arrive at certainty. Instead, he arrives at a crossroads: between history and myth, between land and sky, between revelation and silence. At this threshold stands the serpent, demanding humility. The final secret is perhaps this: that the treasure is not gold but vision — the ability to see the Rennes landscape, and the world itself, as a living temple where every stone speaks and every myth converges.