A world at sunset. An iconological reading of the secret of the shepherds of Arcadia

Article by Mario Arturo Iannaccone (2005)

https://www.renneslechateau.it/index.php?sezione=articoli&id=poussin

With thanks to Mariano Tomatis for permissions to translate articles in the interests of research. Translated by Rhedesium. Following the Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International restrictions placed by author[s]. Publication date 2008 - Usage -Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 InternationalYou are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format & Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The internal meaning of the painting the Shepherds of Arcadia is hidden in a detail. The painter's biographers have no doubt that the inspirer and the commissioner of the painting was Cardinal Giulio Rospigliosi (1600-1669), a Roman patron, who reigned from 1667 to 1668 as Pope Clement IX. Rospigliosi asked the painter for a subject that reminded that "bliss and life are subject to death". In classic clothes, of course, as required by the lasting vogue of those years.

Arcadia felix is one of the most practiced poetic themes starting with Theocritus and Virgil. And also one of the longest-lived because it passed almost intact from the pagan to the Christian period, when it was used as a moral allegory. Taken up by the Humanists, until the mature eighteenth century it remained in the inventories of the poets. Arcadia is a symbol of the happy land and the Golden Age, ruled by wise kings, furrowed by clean streams, dotted with trees that give spontaneous fruits. It is the land in which everyone would like to live, the rediscovered paradise, outside the current of history; the land where, according to a centuries-old poetic codification, people live happily and think only of pleasures, love and friendship. Ideal of the Roman otium, of wisdom according to Ovid.Virgil, the great Augustan poet, had been surged to the level of a prophet, for two of his compositions contained in the Eclogae: the IV (paulo maiora canamus), one of the cornerstos of Western poetry, where he prophesied the renovatio of the world and the imminent birth of a divine child (the son of Pollione probably, then identified in the late-ancient comments as Jesus Christ); and the V where he compared the stone monument destined to last, to the short life of Dafni "similar to that of a swan". Precisely this composition is the literary root of Poussin's subject. Not the only one and in fact Poussin certainly also knew the re-proposal that Jacopo Sannazzaro made with the Arcadia (1502), - a work of extraordinary fortune that had sixty editions in the sixteenth century alone - which contains scenes of shepherds who cry a companion, dismay, in front of his grave. The Arcadia of Sannazzaro inspired hundreds of cantatas and songs populated by Amarilli, Dafni, Lidie, Licori, Titiro and Melibeo.

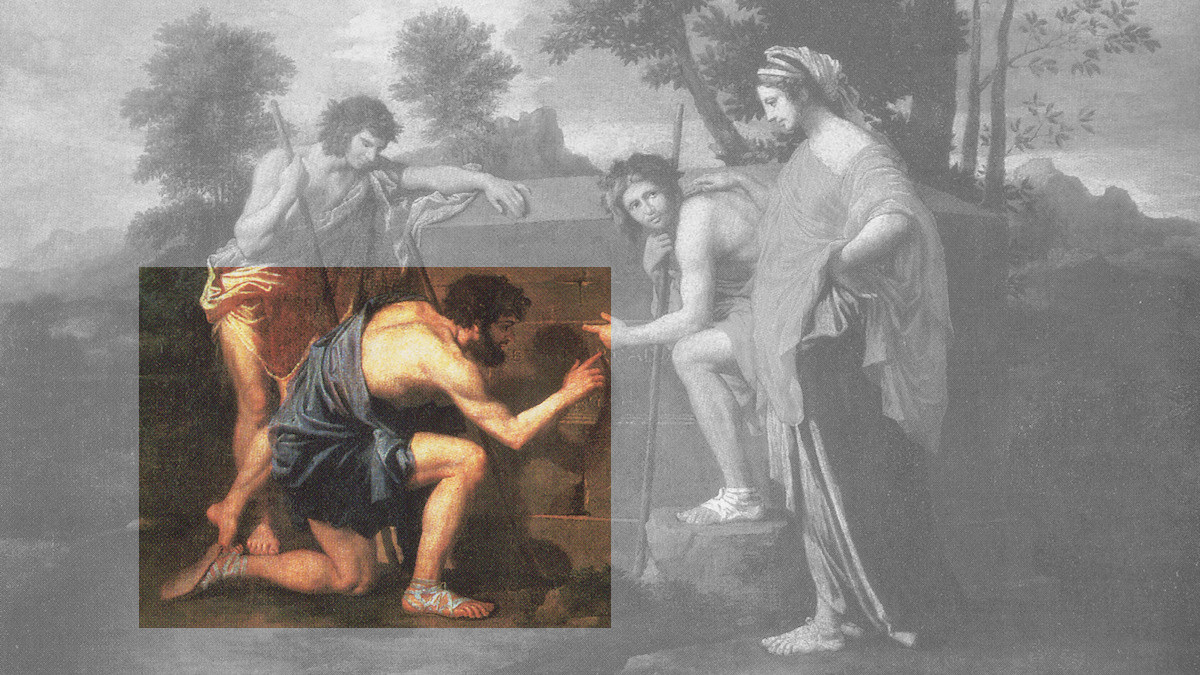

Poetry scene between Melibeo, Coridone and Tiri of the Seventh Egloga. Taken from the Vatican Manuscript 3867, it inspired Renaissance poets and painters for the representation of Arcadia. The characters are shepherds and "graduates" (poets).

We observe the painting, its extraordinary harmony is the result of the rigorous application of the golden section. His sadness is also due to the plastic and slow movements, to the clear but sly light. The deconstruction of the golden ratios makes it possible to identify those dozens of geometric figures, implicit in the texture of the painting, which make a good hand for treasure seekers. But the same figures can be found in all the paintings built according to the pictorial schemes of the period.

One of the most famous meditations on death in the history of painting. Melancholy, immersed in the sunset light of the pagan world, Poussin's sibyl tries to console the shepherds, each of whom has a different attitude. The pastor depicted in the centre "projects" the secret of the painting. Even in this paradise on earth, in this Golden Age where beauty, dignity and elegance reign there is an ungrateful guest. The first terrible clue is the dried source whose groove departs from the foot of the tomb. Poussin and Rospigliosi propose a form of meditation on the most bitter theme of all: the end of earthly life. At this time, art, which had not yet completely detached itself from religious commission, tended not to be a form of simple "furniture" for the rich but rather an aid to meditation, to recover serenity, to consideration on the light and dark sides of life. It was no coincidence that series of emblems were printed (famous those of Andrea Alciato), which had to be memorised, visualised, and then acted in the mind so that they caused a change in the contemplative. The best painting, at least until the eighteenth century, still possessed this spiritual quality.

An iconological reading

There are four figures present. From reading their attitudes, what they wear and from a detail, in particular, one understands the overall meaning of the painting. Three figures meditate on the writing engraved on the grave and seem to ask for explanations from the female figure, who has her head covered. Who does she represent? There are some hypotheses, all very similar, that we are not interested in discussing here. The splendid and noble woman who dominates the painting is not a celestial figure: it can be deduced from the colour of her coat which is orange and from the absence of properly divine attributes. She is not a pagan deity but not even a recognisable Christian figure. She is frequently identified with Isis. But Isis - present in the seventeenth-century culture as a perennialist theme - was not part of the codes of poetry and pastoral-bucolic painting. The most famous, indeed the only description of Isis made by a real initiate to her cult of the Hellenistic era, is the work of Apuleius who, in the XIth Book of the Golden Donkey, clarifies that the goddess was known under several names: Magna Mater (Cybele, Rhea), Minerva, Venus, Diana, Proserpina, Ceres, Juno, Bellona, Hecate, Ramnusia; but her verum nomen is Isis. In the passage of XI, 3 we read that the goddess had "a mass of thick and long hair, slightly curly", that her head was tight by a crown woven of flowers, which emitted a "clear light" (the brightness is typical of the pictorial representations of the divine figures). On both sides of the goddess stood two snakes and spikes "sacred to Ceres". But it is above all her robe that eliminates any doubt. Apuleio, describes a figure dressed in a byso of an iding and undefined colour and black (like the earth); moreover, the bysus is almost silvery (like the moon) and reflects the light of the environment. Isis, lady of waters and fertility was naturally associated with dark or white-blue and lunar colours. Isis is therefore not the figure of the painting, also because none of the other characters has attributes that can come close to characters in the drama of Isis1. The identification is not consistent with the context, it is not plausible for the type of commission and framework and, a decisive reason, is not found in the attributes of the represented character. In fact it is a sibyll. The woman wears her head covered like the sibyls, represented in the side panels of the Sistine Chapel and in many other churches. The sibyls represented the prefiguration of Christian wisdom, that is, the Wisdom of the Ancients in its noblest expression. According to the late ancient tradition, the Italic prophetesses had predicted the coming of Christ. They were depicted as young women in light robes, orange mantle on blue-blue robes (more rarely other colours), just like Poussin's sibyl. Varrone specifies 10 sibyls with detailed symbolic attributes (a musical instrument, a papyrus, etc.). In medieval times the sibyls will become 12 like the prophets. Other times, instrumental attributes were absent. In this case they were pagan "prophesses" who "without tools or ornaments", predict "things that are not laughed at" (Heracl. fr. 92DK), like death. Exactly like in Poussin's painting, where we have a sibyl, without ornament or tools, which alludes to something you can't laugh at.

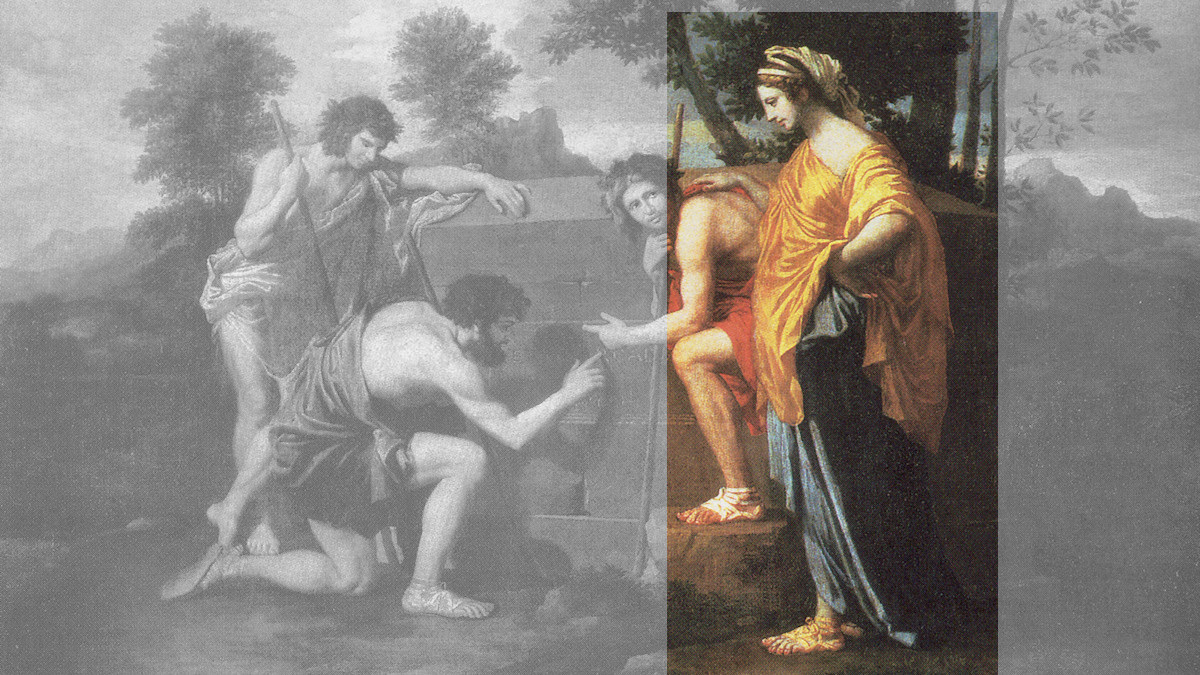

Two sibyls of mannerist period of painters much loved by Nicolas Poussin, born in 1594. On the left the Sibyl of Domenico Zampieri, called Domenichino (1581-1641). On the right the Sibyl of Guido Reni. (1575-1642) Identify both as the Cuman Sibyl. The two prophetesses wear an orange robe and wear the garment covered like Poussin's sibyl.

Considering that it is the Cuman Sibyl that pronounces the oracle in Virgil's IV Ecloga, and that it is always the Cuman who guides Aeneas to the underworld in the Aeneid, the woman represented by Poussin could be the Cuman Sibyl, the main one of all, which became the universal example of pagan pleading wisdom. But without ornaments. For her prediction is certain for men: it is death. And there is no need to tell them that it will come, even if they are happy shepherds of Arcadia.

At the end of the century (for example in the 12 sibyls of the Querini Stampalia collection in Venice) the sibyls will be painted with freer attitudes. However, the Cuman of that collection, even if it does not have the covered garment is dressed in the same colours as Poussin's sibyl.

The Resigned

The posture of the left-shepherd, a "graduate", a poet-pastor, is melancholic, the shoulders are drooping, he seems sad and resigned. He is leaning or rather abandoned on the big grave, as if to want to hug it. His understanding ends there. His gaze is lowered, he doesn't raise his eyes to the female figure. It's like he already knows. In addition, his feet are bare: he is the only character who does not wear sandals.

The shepherd conquered by the thought of death is almost collapsed on the nameless tomb (the tomb of all). We can have no doubt that he is oppressed by the sadness that the awareness of death has brought him.

The man who is consoled by the Sibyl

The young man represented on the right of the painting has a very different attitude. He seems to ask explanations to the sibyl that stands by his side, he seems to ask her questions. Unlike his leftist comrade, he still has questions to ask. He also holds the stick of the shepherds (so he is engaged in the chores of life and probably in them he has been lost until this moment). He too, like the first character, is beardless. But he puts the sandals on his feet, and so we can assume that he will go far because he is looking for it. The sibyl, a representation of foresee and pagan wisdom, tries to console him. She rests her hand on his shoulder as if to support him. But she can't console him to the end. The sibyl that consoles but cannot give joy, immersed in an evening light.

The pastor-philosopher

The centre pastor has the most curious attitude. Point your finger against the stone to highlight the writing Et in Arcadia ego. Not only that, his shadow seems to erase the word ego, as observed in the quality reproductions of the painting. A terrible warning of the fleeting of life. The character is learning to accept the idea that his body will soon no longer exist. He is the most singular character. His attitude is manly, just of those who face reality. In fact, of the three characters he is the only one who has a beard. The presence of the beard is a certain iconological indication of the acquisition of wisdom. Traditionally, ancient philosophers were represented with beards, with a few exceptions. The pastor still represents the philosophical attitude, in the etymological, Greek sense of the word, of love for wisdom (sofia), the discipline that can give a balm to the miseries of life. This pastor-philosopher has loosened his grip on the occupations of life (he released the stick), his deep blue mantle, of detached contemplation, is dyed the same colour as the sibyl tunic. He puts on his sandals and he's the only one who doesn't wear a laurel. He is not a poet - poetry is one of the pleasures of life - maybe he is a philosopher.

The philosopher investigator, who does not dismiss the thought of death, does not seek consolation but looks at it manly, considering its crudest aspect: the destruction of the body.Three stages of deathThe clients and users of these paintings were cultured gentlemen, poets, ecclesiastics, and loved to discover the meanings that the painter concealed in the painting. The iconological density of the paintings of these periods was extraordinary. The secret was inherent in the pleasure of looking at a painting. But this pleasure has unfortunately been polluted by the modern attitude to see "esoteric" meanings, with the belief that there is always something hidden from others for religious, magical or political reasons. This is a modern, very modern attitude. The hidden, hermetic, iconological meanings had the value of making the picture dense, of harmoniously assieparne multiple teachings behind the "letter" of the vision, the simplex locutio.During receptions or in the quiet of friendship, the guests loved to discuss and try to discover what the painter and his client (above all) had intended to teach them in terms of morality, wisdom, wisdom, history and sometimes even in hermetic arts (think of Parmigianino). Probably in our painting there is a second, refined game of meanings that is relevant to the phases of death represented by the three characters and the three colors. When we think that the physics of the time attributed to the three "mobile" elements, fire, water and air, the three phases of the putrefaction of bodies swollen by heat, liquefied in water and dried by air (real phases, observed and verified even today in the disintegration of corpses) one understands how Poussin sublimated this terrible theme with taste and subtle allusion. The three characters could therefore represent the three phases of the return of the bodies to the dust (difully studied in the physics manuals of the time) whose outcome is the earth, represented by the tomb in front of them. The character on the left wears a red robe (fire); the character in the center wears a blue robe (water), his activity is less accentuated; the character on the far left wears a white robe (air). This is the fate of everyone, Rospigliosi-Poussin seems to tell us, and we must get used to the imminent destruction of our body. Demolished by the subsequent action of the three elements we must return to the earth, under a stone.Nothing prevents us from attributing, as has been done, even the alchemical meanings of that spiritual alchemy widely practiced by the cultured of the time, especially in Jesuit circles, where the wisdom of the ancients, the prisca philosophia was recovered from the Christian message. The pictorial art of the most cultured shorts of the seventeenth century was metaphysical, like the poems of John Donne or John Creshaw: he liked to develop more meanings, like bouquets of perfumes that come one after the other. And the game of the spectators was to discover them and to delight in the results of their research activity. But nothing further from the search for treasures. It was an all-intellectual game, and even spiritual, in the happiest cases.The hidden detailHowever, there is a detail that makes the identification of the subject of the painting decisive as a meditation on death, erasure of happiness, and on the impossibility of the pagan world to overcome the sadness of Hades. And this brings us back to the Roman religious environment of Cardinal Rospigliosi who commissioned and paid for the painting. Here its deepest meaning must be sought even if later the literature reports traces of the subjection of meaning to the French Augustan ideology that replaced the mythical Arcadia in the Golden Age of Louis XIV.So bizarre is the ability of the decisive detail to show itself to the consciousness of the observer, and to hide, that very rarely it is identified and retained. From this we measure the genius of the painter who managed to hide it under the gaze of the observer and to represent in us, his spectators, the different attitudes of the shepherds. We observe the shadow cast on the stone of the sarcophagus by the "philosopher" pastor, shoed and detached from the grip of life, who is watching it closely. The shadow of his right arm stretches and curves unnaturally on the stone: it is the shadow of a scythe. There can be no doubt. A skilled painter like Poussin could never have represented the shadow of an arm in that way and with that curve2. The shadow of a sickle, the shadow projected by the body is the visible, chilling symbol of our mortality that shows itself in the middle of daylight, that is, in the middle of life.Starting from the humanistic era, in Italian and French painting the sickle is found both in the theme of the Father Time, and associated with Saturn. Here Poussin operates a brilliant synthesis between the two themes suggesting the presence of the theme of Father Tempo, always represented with the scythe (in turn variation of the theme of the Dry Death) in a scene of "Saturnine" melancholy3. The Time Father, which indicates the falloss of life is here invisible. Poussin elegantly reinterpreted the humanistic theme "by melting it" in the representation.An unnatural shadow projected from the arm deforms to the point of drawing the blade of the sickle of death, the effigy of Saturn the devourer, singer of the attractive and melancholy.Both themes have to do with death. In particular with the caducity of the waist and the physical body the first (Father Time) and with the effects of it the second (Saturn and Melancholy)4.The invincible sadnessThe Pastors of Arcadia are a meditation on death and physical disintegration. The sibyl announces a hope, a light, but it is not enough to dispel the sadness. The tomb in front of which the shepherds meditate on their fate does not have a name engraved because it indicates the fate of all. The "I", individuality is destined for unravelling in the pagan world. There were not a few pagan sages depicted in churches as models of virtue. Religious poetry (starting with Dante) saved pagan personalities, such as Trajan. But these were exceptional cases. The pedagogy of the painting can be compared to the famous step of Lucretius who witnesses a shipwreck and rejoids in his luck. The contemplant of the painting while sharing the physical destiny of the shepherds of Arcadia is (or can be, if he wants) saved.That is why the pagan world of Poussin's Shepherds is melancholic, because, in the painter's mind, (and his patrons of the Roman curial circles), it has not yet been saved by the incarnation of Jesus. This Arcadia that foreshadows salvation, and meditates on death, is caught in the light of the sunset. The clouds at the bottom have the shades of the evening. Behind the shoulders of the sibyl the evening seems to have already arrived, the colors are dark, the trees sparse, autumnal. The painter seems to suggest to us that what is represented is a world that is about to end. The sadness of the sibyl with a head reclining, helpless, also indicates this: how the Cuman predicted the salvation that will come from the "divine child" but (perhaps) not for these men. Who meditate on a stone in comparison to which they have the substance of a shadow. In front of a land that is not a mother, a tomb that bears the macabre effigy of the Father Time, Cronus the devourer: the sickle.Most likely, the landscape has nothing to do with the Rennes area. The cultured, sly, sly activity of Maurice Leblanc, normand as Poussin, born like him near Gisors, would have converged a series of clues, - partly inheriting them in part by creating them - which gifted emules would have translated into "tangible evidence".But that's another story.1. Apuleius, The metamorphosis or the Golden Donkey, translate. Of C. Annaratone, Rizzoli, Milan 19813, pp. 649-651.

2. Quoted P., The light of the night, Mondadori, Milan 1996, pp. 318-320. Quoted from a wonderful reading of the painting.

3. Panovsky, Studies of iconology, Einaudi, Turin 1975, pp. 89-134. For the use of Saturn in pictorial iconology, the fundamental text is Saxl F., Saturn and melancholy, Einaudi, Turin 1983. In the doctrine of the four humors, Saturn presided over bile, associated with stone.

4. Other paintings by Poussin contain Saturn in the appearance of Father Time (also called Great Maleficent), Ball of Human Life and Aelius, Feton and Saturn with the Four Seasons (1635 ca). In Renaissance and Mannerism painting, Saturn also alludes to the Golden Age as in The first fruits of the earth offered to Saturn by G. Vasari of Palazzo Vecchio in Florence (1555-1557). The reference to the Golden Age naturally derives from the Greek myth, especially from the Theogony of Hesiod.