Pierre Plantard - From Archives to Myth: The Esoteric Sources of Pierre Plantard

Pierre Plantard occupies a central place in the Rennes-le-Château affair, yet the truth about what he actually knew, when he knew it, and how he acquired his knowledge remains elusive. This last question—how he came by his information—is particularly crucial. And in the process of answering these questions we are left with a final thought - why did Plantard do all this? To bolster his ego? To make money? Or did he truly know some unknown secret about the Two Rennes?

Some view Plantard as a latecomer to the Rennes-le-Château Affair, appearing “officially” in the early 1960s after encountering press accounts of the mystery written by Robert Charroux and Noël Corbu. Others, however, argue that he had access to relevant material much earlier, evidence of which surfaces in scattered references throughout his various publications. These pieces, over time, coalesced—or, perhaps more accurately, were carefully arranged—into the Rennes myth as it emerged in the 1960s, suggesting a depth and obscurity in the knowledge he shared.

Plantard appeared to be far more interested in the village of Rennes-les-Bains and what remains unclear is whether Plantard genuinely possessed knowledge of a specific “mystery” there. Some speculate his approach was more deliberate, only disseminating fragments of information to select confidantes and friends without ever revealing the full picture. What is indisputable, however, is that the village of Rennes-les-Bains held significance for him: he bought land there, he lived there for a time, and, as Philippe de Chérisey reports and hints in his novel CIRCUIT, Plantard’s presence in the area was long-standing and associated with a particular part of the village and folklore attached to a house there, as well as its connection with the village priest Henri Boudet.

Pierre Plantard did own land in the Rennes-les-Bains area, specifically at Blanchefort and Roc Negre. By 1972, he had purchased substantial property there, which he later associated with his narratives about the Priory of Sion. While Plantard's land ownership in the region is documented, the significance he attributed to these properties is part of the elaborate mythos he constructed. He claimed that these sites were linked to ancient secrets and royal lineages, but these assertions are widely regarded as part of his esoteric inventions. In other words, while he physically had property there, there’s no independent evidence that these sites were tied to secret treasures, ancient manuscripts prior to his interventions. This is apart from the work by Henri BOUDET in La Vrai Langue Celtique et la Cromlech de Rennes-les-Bains [we will look at this the next article].

Again why did he do this and what did he know?

Plantard leveraged his land ownership in two main ways:

- Geographical Credibility: By buying land and living in the area, he could present himself as someone with direct access to the “secrets” of Rennes-les-Bains. This gave his stories of hidden knowledge a veneer of legitimacy, even though the actual claims were fabricated.

- Mythic Anchoring: He tied specific locations he owned (or nearby landmarks) to elements of the Priory of Sion legend and the supposed Merovingian mysteries. For example, he and his collaborators would hint that certain points on maps, churches, or estates were markers of esoteric knowledge. This gave his fictional narratives a tangible “real-world” anchor, making them appear historically plausible.

In essence, the land holdings are either props in his myth-making or they are the actual source of it. It allowed him to blur the line between reality and fiction: he lived there, so he must know something, and thus his imaginative reconstructions of history and secret societies could be presented as credible.

Examples of Property + Mythic Claims

| Property / Parcel | What Plantard Claimed / Did | How It’s Used in the Myth |

|---|---|---|

| Parcels around Roque Nègre (Mount Blanchefort) | Plantard acquired several parcels: N° 633, 634, 635, 616, 636, 647, etc., around Roque Nègre. In 1971 he bought parcel 647 & 658. In 1974 he bought parcel 645. He also attempted to buy more, including parcels 645, 646, etc. | These parcels are claimed to include or border “Roc Negre” / “Roque Nègre” (also called “Black Rock”) and “Temple Rond” / “Round Temple”, a supposed underground Celtic or ancient temple beneath or by Roque Nègre / Château de Blanchefort. Plantard used these claims to locate secret subterranean structures, treasure, or sacred spaces. |

| “Roc Negre” / “Roc Noir” / Black Rock | He claimed that Roc Negre was part of what he owned, or at least that he had land there. Also, he used older legends (e.g. of mining & hidden subterranean vaults) associated with Roc Negre, and mixed them with his own claims. | The mythic function of Roc Negre is as a locus of secrets: entrance to the “Round Temple,” repository of hidden treasure, site of ancient mines, etc. It anchors the myth physically in his land, giving credibility or at least plausibility. |

| Château de Blanchefort / Blanchefort region | The ruins of the Château de Blanchefort are tied in: Plantard claims the temple entrance is beneath or by the château (or its grounds) via Roc Negre. He bought land around Blanchefort (as mentioned above). | This gives a visible landmark (ruins of Château) to which a mystery can be attached. It allows him to say: “This abandoned castle, which I partly own (or control land near it), hides something secret.” It helps blur lines between real places and invented secrets. |

| Attempts / purchases of houses, concessions | He tried to buy from André Flamand several parcels & parcels of land; also tried to buy Flamand’s house in Rennes-les-Bains. He also obtained a perpetual concession at the Rennes-les-Bains cemetery (though not ultimately buried there). | Having physical property + legal control (or attempted control) allows more plausible “stewardship” of secrets. Owning land near / over supposed underground sites gives the ability to claim access (or at least “some right”) to hidden features. |

| Mining legends tied to the land | The Roque Nègre / Blanchefort area is associated with legends of ancient mines (gold, copper, etc.). Plantard used old stories, e.g. those connected to Jean Louis Dubosc, miners, “mines légendaires anciennes”, and claimed that the underground temple or sacred sites are connected to these mines. For example: a story of mining for auriferous deposits; entrance below Roc Negre; alleged underground passages or “round temple” beneath. | These legends provide “historical resonance” for Plantard’s invented stories. If people already believe there were mines, hidden tunnels, etc., then the claim of hidden temples or lineages is more plausible. It also lets him anchor his myth in local legend and topography: underground features, mines, castle ruins, etc. |

Critical Points

- No verifiable archaeological basis: Many of the “underground temple,” “round temple,” “secret chamber” claims have no reliable archaeological confirmation. They depend on unverified or forged “documents,” conflated local legends, and Plantard’s own writings. Cherisey however elaborates alot about an underground Temple situated at Rennes-les-Bains and others have researched legends attached to the land of the Marquis de Fleury at Rennes-les-Bains and some of the references are from local archaeological societies at the time of Henri Boudet & Bérenger Saunière.

- Use of older legends & archives: Plantard often refers to older legends (e.g. of Dubosc, of mining, of local folklore), mashed up with private or obscure archival materials. But in many cases the archival sources are unverifiable, or used in ways that suggest mythmaking rather than historical reconstruction.

- Changing stories over time: The details of what is claimed shift: parcels bought change, names of temples change, what exactly is said to be hidden moves. For instance “Temple Rond” appears in texts in the 1980s/1990s covering earlier eras. This suggests retrofitting or evolving myth rather than consistently held secret knowledge.

Putting it together:

Plantard’s personal history during these years building up to the myths is shadowy. He was briefly imprisoned, though the records are contradictory. Robert Amadou and Massimo Introvigne both note accusations of fraud in 1953, for allegedly selling esoteric “degrees” for exorbitant sums. Yet a police report from 1954 curiously asserts he had no criminal record after they searched the files. There is also the claim that he was detained by the Germans during the Occupation, for abuse of a Minor, in Fresnes Prison. The contradictions leave room for speculation that Plantard himself blurred the facts to enhance his mystique.

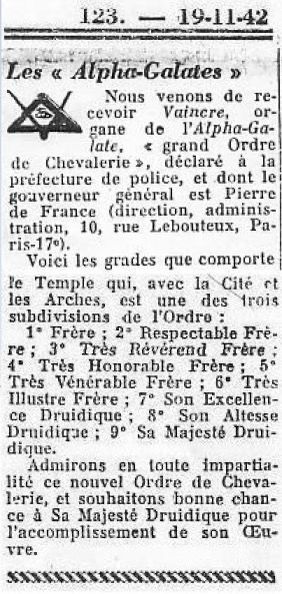

From the 1930s onward, Plantard moved within a milieu steeped in occultism, monarchist politics, and esoteric Catholicism. His early ventures included the creation of a group, the French Union and later the Alpha Galates, a grandiose order with quasi-Masonic initiations culminating in the title of “Druidic Majesty.” His circles [according to the police reports] overlapped with radio actors, right-wing thinkers, and heterodox esoteric Christians. And through Gérard de Sède it is posited that through family connections, Plantard was linked with the Zaepffels, a Breton couple fascinated by spiritualism and the Grail legends. Their cook, Amélie Raulo—Plantard's mother, the widow of Plantard’s father—brought the young Pierre with her when she went to work for her.

The Zaepffels, particularly Geneviève, were immersed in spiritualist prophecy and Celtic revivalism, hosting gatherings at their Manoir du Tertre in Paimpont. There, amid talk of druids, fairies, and Grail visions, the young Plantard was exposed to a heady mix of folklore, mysticism, and esoteric speculation. It may explain his preoccupation with the Two Rennes, Camp Redon and Celtic assertions within the Rennes Affair. This environment, combined with access to confiscated archives and postwar publishing ventures, provided him with an arsenal of themes—from Egyptian rites to Templar legacies, from Grail myths to apocalyptic prophecies—that would later crystallise in the Priory of Sion.

By 1956, Plantard had formally registered the Priory in Annemasse under the title “C.I.R.C.U.I.T.” (Chivalry of Catholic Rule and Institution and of Independent Traditionalist Union). His political sympathies leaned Gaullist, echoing the Zaepffel milieu, and Charles de Gaulle himself, Plantard claims, sent a polite acknowledgment of support. From there, the tangled network of Plantard’s claims, connections, and fabrications grew into the sprawling legend that continues to cloud the Rennes-le-Château mystery. Seen in this light, Plantard was not simply an opportunist who joined the Rennes affair late, but a figure whose formative years immersed him in overlapping worlds of occult speculation, esoteric rites, political intrigue, and archival secrets. Out of these strands, he wove a mythology both compelling and confounding—a mythology that still leaves us asking: what did he truly know, and from where did he draw it?

The connection between his life-history, land holdings and the broader Rennes-le-Château mystery is thus intertwined with his own myth-making rather than historical fact. Plantard deliberately purchased (or attempted to purchase) land in areas like Roque Nègre / Blanchefort near Rennes-les-Bains. He used these properties as loci in his mythic geography.

- By connecting those physical properties to folklore of ancient mines, hidden underground temples, “Devil’s Treasure” stories, and supposed genealogical claims (for example, of Merovingian descent, or Priory of Sion), he lent his fabrications a tether to tangible geography.

- But there is no independent, credible evidence that any of these places—parcels he owned—ever did hide the secret treasures, manuscripts, or ancient temples as he later claimed. Much of the “mythic geography” seems to stem from his own inventions or reinterpretations of folklore, rather than records that pre-date his involvement.

This scattered evidence of Plantard and it's puzzle is never more illustrated and highlighted than by the comment made by Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend in their study of ancient star lore, Hamlet’s Mill. There, they noted with some surprise that Gérard de Sède had quoted “the archaeologist Pierre Plantard” in Les Templiers sont parmi nous (1962), attributing to him the remark: “Canopus, the sublime eye of the architect, which opens every year to contemplate the Universe”. They wrote;

"“We should be glad to learn, moreover, where the archaeologist Pierre Plantard [?] got hold of the information on “Canopus, The sublime eye of the architect, who opens his eyes every 70 years to contemplate the Universe.”

The full quote from Plantard was from an interview he gave [Interview with a Hermticist] in de Sède’s book:

“The Chariot of the Sea, the White Ship of Juno with the sixty-three lights of which Canopus is one, the sublime eye of the architect, which opens every seventy years to contemplate the Universe, the ship Argo that transported the Golden Fleece, in Christianity the modest barque of Peter. It is the symbolic Ark where nothing profane can penetrate without incurring punishment: ‘To the sacriligious a fall, to the thief death within a year.’ Only those who are capable of working the cube of the wood of Mars – that magic ‘die’ entrusted to the vigilance of two children: Castor and Pollux – to perfection, in every sense, can enter there. Trying to penetrate through the Hermetic as quickly as possible, the star Canopus was identified with the eye of God, who looked at the Universe every 70 years".

Canopus (alpha Carinae) is the second-brightest star in the night sky, tied in mythology to Jason’s ship, the Argo. Its symbolic weight is great, but its mention in such an arcane context raises the obvious question: where had Plantard obtained this kind of information?

One possible answer has been offered by John Saul in An Extra Player on the Playing Field of History. He situates Plantard’s sources in the turbulent wartime years, when Freemasonry was systematically suppressed under the Vichy regime, and the moral fight between Freemasons and the Catholic Church [a whole point of interest in itself!]. Beginning in 1941, the French government, under Marshal Pétain, confiscated vast Masonic archives—records stretching back into the nineteenth century—including those of the esoteric Rites of Memphis and Misraïm. These rites, with their claimed links to Egypt and the Knights Templar, though sometimes dubious, nevertheless preserved traditions with a powerful imaginative appeal.

According to Saul, these materials were gathered at the Centre d’Action et de Documentation (little is known about the CAD, which has undoubtedly played an important role in the anti-masonic repression of the Nazi years. Installed in the premises of the Grande Loge de France, 8 rue Puteaux, funded by the Germans, it was divided into 4 sections and had a network of correspondents in the regions responsible for investigating anti-collaborationist elements. It recorded several thousand suspects and distributed throughout France several thousand copies of an Anti-masonic Information Bulletin-La Libre Parole written largely by Coston, a tireless polygraph participating in the publication of many anti-Jewish papers (Au pillori, Je vous hais, etc) in Paris, located only a short walk from where Plantard and his mother lived. He suggests that Plantard, perhaps through connections with Henry Coston, gained access to this cache of confiscated documents during the early 1940s.

Coston, a collaborationist journalist, salvaged Drumont’s anti-Dreyfusard weekly La Libre Parole, and contributed to the infamous Au Pilori. ["Au Pilori" refers to an anti-Semitic newspaper published in Occupied France during World War II]. He had connections to the editors of Au Pilori, particularly through his involvement in other collaborationist publications during the Vichy regime. He directed Documents maçonniques, a monthly publication edited by the Centre d'action et de documentation. Bernard Faÿ, a collaborator and contributor to Documents maçonniques, was associated with Au Pilori. Moreover, Coston's secretary during this period was Henri-Robert Petit, who later became the editor-in-chief of Au Pilori. These connections suggest that while Coston was not an editor of Au Pilori, he was closely associated with individuals who held editorial positions within the publication.

Plantard himself was mocked in Au Pilori when his chivalric society, Alpha Galates, and its extravagant “Druidic” grades were lampooned in print.

One does wonder if the links with this mocking of Plantard by the Au Pilori team and perhaps if Plantard had incurred their later displeasure these people could have been instrumental with the assistance of the German authorities investigating Plantard to get him jailed?

These first anti-Masonic measures were by the Germans on their entry into France. In their search for documentary evidence to prove a Franco-British collusion to provoke the War, they sealed lodges and confiscated documents to prove their theory. They were also trying to lay their hands on the mythical treasure of the lodges to support their war effort. The Germans were not too concerned about the fate of individual Masons and their persecution of the Masonic movement would probably have paralleled the treatment it received in Germany itself and other Occupied countries.The Germans were not interested in hunting down Freemasons or persecuting them but only in acquiring archives and documents to prove their theory of an international Judeo-Masonic plot and perhaps to investigate the possibilities of a Masonic treasure.

Saul believes Plantard may have been authorised—or at least allowed—to mine these archives for material, some of which later surfaced in his journal Vaincre and, eventually, in the mythos of the Priory of Sion. Saul says that maybe Plantard had recognised some broad importance in these papers but had initially been unable to do much of anything with them & by one way or another Plantard's possession of these documents had enabled him to acquire financial support and intellectual help in the late 1950's.

Massimo Introvigne asserted that Plantard 'went to jail for six months at the end of 1953, accused of selling degrees of esoteric orders for exorbitant sums'. According to Robert Amadou, Plantard in 1953 was accused of selling degrees of esoteric orders for exorbitant sums and in a letter written by Léon Guersillon the Mayor of Annemasse in 1956, contained in the folder holding the 1956 Statutes of the Priory of Sion in the subprefecture of Saint-Julien-en-Genevois, Plantard was given a six-month sentence in December 1953 for abus de confiance (breach of trust), relating to other crimes.

Was this breach of trust for a kind of fraud? A police report from a YEAR later after his supposed imprisonment, on 4th May 1954 confirms that; "On the subject of the arrest of Monsieur PLANTARD, his mother states: 'My son was arrested by the Germans on a date that I am unable to recall precisely, as I suffer from amnesia. His apartment was not searched by the French police but by German gendarmes accompanied by German civilians. My son remained in Fresnes Prison for 4-5 months where he was subjected to numerous physical abuses'."

Apart from the quite humorous response given by his mother [I suffer from amnesia!] she reports he suffered physical abuse. The report also stated that 'Checks made with the various departments of the Prefecture of Police have not revealed any trace of the arrest of Monsieur PLANTARD. He does not have a criminal record".

Yet he was supposed to be imprisoned in 1953.

Introvigne also referred to Eugène Deloncle, who created a group known as CSAR (Secret Committee for Revolutionary Action), nicknamed “La Cagoule”. He claimed that 'one high school student who followed Deloncle and ran into trouble with the police, without being involved however in any terrorist activity, was Pierre-Athanase-Marie Plantard, the son of a butler and a concierge who was so much in love with the Monarchy to invent for himself imaginary aristocratic and even Royal genealogies. In 1937, Plantard dropped out of high school and established with some of his friends the Union Française (French Union), a group inspired by Deloncle’s ideas but probably without any contact with Deloncle himself, who was at that time operating underground.'

Other connections appear. Raymond Abellio - the pseudonym of Georges Soulès - after developing a long literary career—evolved into a lifelong fascination with esotericism and astrology, and had once also been deeply involved in politics. In 1942, he became secretary general of Eugène Deloncle’s far-right party, the Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire (MSR). Deloncle’s family [origins in Britanny France], in turn, was connected at the highest levels of French society: his niece, Édith Cahier, married Robert Mitterrand, the brother of future president François Mitterrand. Pierre Plantard’s family, too, appears woven into this network. It is reported that Plantard had a cousin, Jean Plantard, son of a François Plantard—likely Pierre’s brother. This François Plantard was closely linked to André Rousselet, a trusted confidant of François Mitterrand. The tie becomes even more striking when one learns that Rousselet’s adopted daughter, Chantal, married Jean Plantard. In other words, the adopted daughter of Mitterrand’s closest ally became part of the Plantard family.

François Mitterrand's itinerary between 1935 and 1942 has been the subject of many contradictory interpretations. Previously, in 1934, he had joined the National Volunteers, a youth organisation of the Croix-de-feu and, in 1935, participated in a demonstration organised by the Action française, which is attested by two photographs. He is a resident of the boarding school of the Marist fathers at 104, rue de Vaugirard, whose residents then frequent the chiefs of the Cagoule, without joining it. Other members of the Mitterand family also have connections with the Cagoule: Robert Mitterrand, brother of the president, married Eugène Deloncle's niece in 1939. François Mitterrand's sister, Marie-Josèphe de Corlieu, was, from 1941 to 1947, the mistress of Jean-Marie Bouvyer, a former La Cougoule member. The latter's mother, Antoinette, became in 1946 the godmother of Jean-Christophe Mitterrand. It is proven that the former President of the Republic has never joined the terrorist organisation. However, the "rumour" will continue throughout his political career.

Jacques Corrèze, became Deloncle's secretary and confidant in 1936. After the armistice, in June 1940, he joined the Revolutionary Social Movement (MSR) launched, with the blessing of Berlin, by Eugène Deloncle and he actively plotted in this anti-communist organization from the first hour and which advocated total collaboration with the Nazi occupier. In 1941, Jacques Corrèze joined the Legion of French Volunteers (LVF) to fight alongside the Nazis against the Soviet Union. He will be in December 1941 a few kilometers from Moscow. On his return to France he made contact with the Resistance, but remained at the side of Eugène Deloncle. He witnessed the murder of Deloncle by the Gestapo (January 7, 1944). Corrèze married Mrs. Mercedes Deloncle.

Paul Cahier was the brother of Mercedes Cahier [Mercedes married Deloncle] and he married Henriette DESBARATS and had a daughter, Edith Cahiers, who married Robert MITTERRAND.

Eugène Schueller hired Corrèze, in his company and entrusted him with the position of general agent of the L'Oréal-Monsavon group for Spain and Latin America. He created the company Productos Capillares (Procasa). He will employ Henri Deloncle brother of Eugène, Louis Deloncle son of Eugène, Thierry Servant son of Claude Deloncle and André son of Jean Filliol.

Schueller provided financial support and held meetings for La Cagoule at L'Oréal headquarters. L'Oréal hired several members of the group as executives after World War II, such as Jacques Corrèze, who was CEO of the US operation.

Taken together, these interlocking relationships form a curious web: Deloncle’s niece married into the Mitterrand family; Deloncle’s right-hand man, Abellio, not only had insider knowledge of Pierre Plantard but was also later associated with Belisane Publishing; and, through Rousselet, Plantard’s family became connected—albeit indirectly—to Mitterrand’s inner circle.

Belisane published the journals of the Gerard Nerval Society and also later out of print books on Rennes-le-Chateau. In fact, after the war, the above cited Henry Coston and other collaborationist authors emerged from prison & were given a new start by Noel Jacquemart (1909-1990), the Director General of the magazine Le Charivari. [Issue #18 of Jacquemart's Le Charivari, for October-December 1973, reproduced the "The Archives"and "Statutes of the Association of the Priory of Sion' [founded by] Pierre Plantard, aka Chyren", in “Annemasse, May 7, 1956”].

Plantard apparently boasted about being in touch with political circles and maybe it was true?

The Masonic links to the Rennes affair grow denser on closer inspection. The rites of Memphis and Misraïm traced themselves back to the late eighteenth century and the Philadelphes of Narbonne, established by the Marquis de Chefdebien. Members of this family had connections to Rennes-le-Château through the Hautpoul line, the same family later woven into Plantard’s and de Chérisey’s fabrications surrounding the “Saunière parchments.” Perhaps Plantard obtained insider information from these files confiscated by CAD? Even more intriguingly, Alfred Saunière, the brother of Bérenger Saunière, once worked as a tutor to the Chefdebien family before being dismissed amid a claim that he stole documents from them. Some of these threads would reappear in Plantard’s postwar creations, bolstered by texts of J.-É. Marconis de Nègre concerning the sage Ormus and the Disciples of Memphis.

From the 1930s onward, Plantard moved within a milieu steeped in occultism, monarchist politics, and esoteric Catholicism. His early ventures included the French Union and later Alpha Galates, a grandiose order with quasi-Masonic initiations culminating in the title of “Druidic Majesty.” His circles overlapped with radio personalities, actors, right-wing thinkers, and heterodox esoteric Christians such as Paul Le Cour. He probably met Cherisey through these contacts, as Cherisey was a some time actor and radio personality. Plantard has claimed before he met Cherisey at 'university'. The details are a bit murky. Plantard often blended fact, memory, and myth in his stories, so it’s unclear which university he was referring to or whether this meeting actually took place in a formal academic setting.

Through other family connections, Plantard was also linked with the Zaepffels, a Breton couple fascinated by spiritualism and the Grail legends.

The Zaepffel’s had moved to Paimpont from Paris in 1933. They brought with them their cook, Amélie Raulo, the widow of Pierre Plantard’s father. Presumably for Amélie to get a job with the Zaepffel's she could have already known them in Brittany [she came from the Britanny area although she was originally born in Doulon (Loire-Atlantique) in the Pays de la Loire region, on January 12, 1884] but then again she could have met the Zaepffel’s in Paris because in 1911, Amélie was a maid, living at 73 avenue des Champs-Élysées.

She married Pierre Plantard, a valet de chambre [the term is used to describe a personal servant who performs similar duties for a modern employer. The term can also be a more formal or archaic way of referring to a personal valet] on November 23, 1911 in Paris (7th arrondissement). Her parents, living in Dol [Dol-de-Bretagne a commune in the Ille-et-Vilaine département in Brittany] were also present. This probably indicates that Amélie Raulo was originally from Britanny.

Amélie Raulo takes her son Pierre with her to Paimpont, who was then of school age. This introduces him to not only the work of Zaepffel as well as the work of her friend Paul Le Cour - with his links to the personages of the occult revival at the time of Sauniere as well as of course the work of Geneviève Zaepffel . Plantard also used the work of Le Cour to form his Priory and references to Le Cour can be found in LSR.

So we have various swirling suggestions of files and information being stolen/come by/pilfered and these sources included Masonic and occult Society archives.

Geneviève Zaepffel worked originally in Rennes at the Hotel Du Guesclin, Place de la Gare.

It was here that she met René Zaepffel there.

Geneviève and René married civilly on October 14, 1921 and religiously the next day in Paimpont. This marriage opens the doors to a certain Parisian environment fascinated by occultism. The couple moved to Paris at 54, rue Legendre in the 17th arrondissement. The Zaepffel parents live at 17 on the same street, in an apartment that the couple will occupy upon the death of René's mother in January 1939.

In 1928, Geneviève Zaepffel founded the Paris Spiritualist Centre at 16 Avenue de Wagram, which became the hub of her activities until 1944. The Centre issued its own journal, the Monthly Bulletin of the Spiritualist Centre of Paris (1931–1941), where her prophetic messages were published. This address lay only a few streets from where Pierre Plantard’s mother was living and working, making it highly likely that the two women met.

There is a cross over with the Masonic history because Geneviève's husband managed publications of the Spiritualist Center of Paris, and published a periodical entitled the National Arche. It deals with various subjects including: Freemasons and Jews, the national revolution, France facing its duty. In November 1942, he declared: Jews and Freemasons continue to govern our country through interposed persons. In this troubled pre-war period when spiritism was in fashion, Geneviève Zaepffel built the image of a high priestess and presented herself as a medium. She published her first prophetic work in 1930. The Zaepffels, were immersed in spiritualist prophecy and Celtic revivalism, hosting gatherings at their Manoir du Tertre in Paimpont. There, amid talk of druids, fairies, and Grail visions, the young Plantard was exposed to a heady mix of folklore, mysticism, and esoteric speculation. This environment, combined with access to confiscated archives and postwar publishing ventures, provided him with an arsenal of themes—from Egyptian rites to Templar legacies, from Grail myths to apocalyptic prophecies—that would later crystallize in the Priory of Sion.

Zaepffel’s prophetic and political ambitions grew bolder during the war. In 1939 she telegrammed Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, urging him not to “declare a lost war in advance.” That same year she wrote to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in apocalyptic terms, warning that at “the first weakness you will leave, at the second you will no longer be.” On 9 December 1940, speaking at the Salle Mustel, Avenue de Wagram, she proclaimed herself “the missionary sent by God to save France,” and announced her intention of advising Marshal Pétain personally, guided by her “spiritual masters.”

In 1942 she founded the Arche Nationale, aligned with the Pétainist “return to the earth.” From her manor she launched schemes to support rural communities whose men were in captivity, equipping tractors at her own expense and offering young people agricultural apprenticeships as part of a quasi-spiritual “family of the Ark.”

After the Liberation her fortunes changed. On a pilgrimage to Lourdes in April 1945, she claimed to have received a vision of the Virgin foretelling her imprisonment. Indeed, upon her return to Paris she was arrested and eventually imprisoned in Fresnes—the very prison where, years later, Pierre Plantard would also serve a sentence for his activities with the group Alpha Galates.

Zaepffel, who styled herself as “a Breton woman, born in the Brocéliande forest, land of druids and fairies,” wove her personal mythology around Celtic legends and Joan of Arc. She claimed her birthplace carried occult radiance, guarded by the fairy Viviane, whose “prophecy” of Joan of Arc she saw as a foreshadowing of her own mission. Even late in life she maintained these legends, identifying a stone sink in her garden as “Viviane’s bathtub” and presenting her manor as a place of prophecy and Arthurian resonance.

Plantard’s own trajectory mirrored, in curious ways, the prophetic-political blend of Zaepffel’s milieu. In 1951, after marrying Anne Léa Hisler, he left Paris for Annemasse near Lake Geneva. There he was jailed again in 1953—sources differ on whether for fraud or extortion—though a 1954 police report curiously records no prison term. On 7 May 1956 he legally incorporated the Priory of Sion (C.I.R.C.U.I.T.), whose politics echoed Zaepffel’s, supporting General de Gaulle, who would later acknowledge Plantard’s letter of support with a polite note of thanks.

As Jean Markale later recalled, Zaepffel’s Manoir du Tertre was steeped in Arthurian fantasy. She proudly told him that the staircase of the Manor is where “Joseph of Arimathea, carrying the Holy Grail from Palestine to Brittany, passed on this very staircase.” [pictured below]. For Markale, it was a tale “too beautiful and too naïve” to answer with criticism. Yet it illustrates the mythic atmosphere in which Plantard grew up—a world where Celtic legend, esotericism, politics, and prophecy fused into a powerful imaginative environment.

By 1956, Plantard formally registered the Priory in Annemasse under the title “C.I.R.C.U.I.T.” (Chivalry of Catholic Rule and Institution and of Independent Traditionalist Union). His political sympathies leaned Gaullist, echoing the Zaepffel milieu, and Charles de Gaulle himself sent a polite acknowledgment of support. From there, the tangled network of Plantard’s claims, connections, and fabrications grew into the sprawling legend that continues to cloud the Rennes-le-Château mystery.

Seen in this light, Plantard was not simply an opportunist who joined the Rennes affair late, but a figure whose formative years immersed him in overlapping worlds of occult speculation, esoteric rites, political intrigue, and archival secrets. Out of these strands, he wove a mythology both compelling and confounding—a mythology that still leaves us asking: what did he truly know, and from where did he draw it?

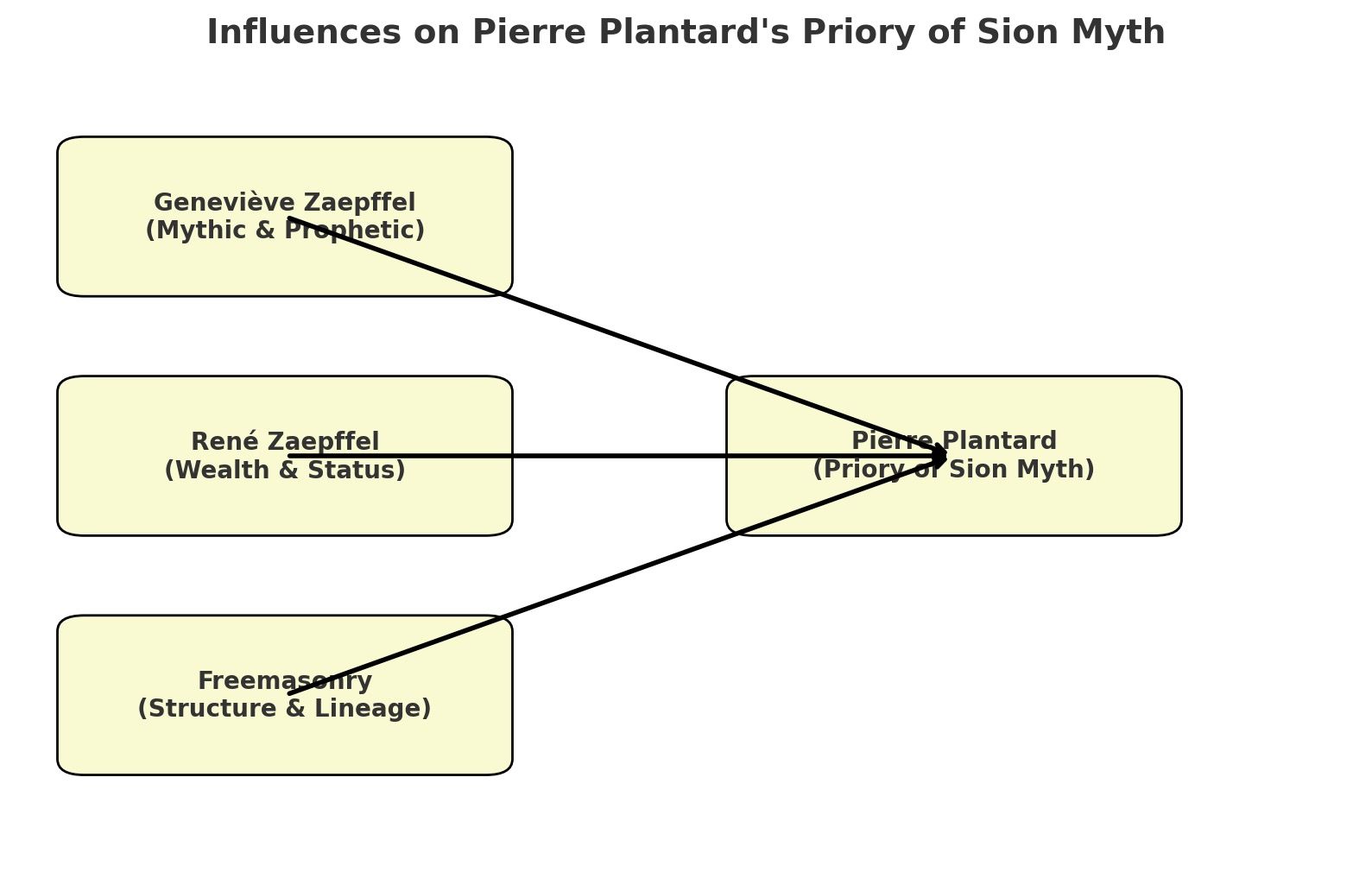

Here are the main points of influence on Pierre Plantard drawn from the text, in clear bullet points:

- Proximity to Geneviève Zaepffel’s circle

- Plantard’s mother worked as a cook for Zaepffel, bringing young Pierre into her environment.

- The Paris Spiritualist Centre (near his mother’s residence) likely facilitated early contact.

- Exposure to spiritualism and prophecy

- Zaepffel ran the Paris Spiritualist Centre, issuing prophetic messages.

- Her world was steeped in visions, apocalyptic warnings, and a sense of divine mission for France—ideas Plantard later echoed.

- Immersion in Celtic and Arthurian mythology

- Zaepffel rooted her identity in Brocéliande, land of druids and fairies, and invoked Viviane and Merlin.

- Her manor at Paimpont was presented as a Grail site, shaping an atmosphere of myth-making Plantard later drew upon.

- Blending politics with esotericism

- Zaepffel corresponded with political leaders (Daladier, Chamberlain, Pétain) in prophetic terms.

- Her project Arche Nationale combined spiritual rhetoric with social policy, echoing Plantard’s own later attempts to tie esoteric orders to political causes.

- Models of charismatic authority

- Zaepffel proclaimed herself “missionary sent by God to save France.”

- Plantard later cast himself as “Grand Master” of the Priory of Sion, claiming hidden authority and prophetic insight.

- Experience of imprisonment

- Zaepffel was imprisoned at Fresnes in 1945; Plantard would also be jailed at Fresnes years later—parallels reinforcing the motif of persecution and martyrdom.

- Connection to General de Gaulle

- Zaepffel’s orientation toward nationalist revival aligned with Plantard’s later positioning of the Priory of Sion as pro-Gaullist.

- The myth-making environment

- Zaepffel’s mix of spiritualism, Celtic myth, prophecy, and politics created the cultural atmosphere in which Plantard grew up—encouraging him to weave esotericism, history, and power into his own elaborate constructions.

René Zaepffel (Geneviève’s husband) is often overlooked, but he provided a very different kind of influence on Pierre Plantard than Geneviève’s mystical visions. Here’s how his role fits in, alongside hers and the Freemasons:

- Financial patronage / social standing

- René Zaepffel’s fortune funded the transformation of the Manoir du Tertre, giving Geneviève the means to project her spiritual authority.

- This exposed Plantard, through his mother’s employment, to an upper-class milieu—teaching him how money and status could underpin spiritual or esoteric authority.

- Elite networks

- The Zaepffels entertained artists, intellectuals, and mystics at the manor.

- This provided Plantard with early exposure to the blending of culture, myth, and influence among elites—a pattern he later imitated by trying to connect the Priory of Sion to famous names and secret lineages.

- Political positioning

- As a wealthy landowner, René represented the conservative, Pétainist-leaning milieu of Brittany.

- His resources helped Geneviève launch ventures like the Arche Nationale, blending land, tradition, and politics—again prefiguring Plantard’s fusion of esotericism with nationalist politics.

- Model of enabling “authority figures”

- René’s role was to bankroll and legitimise his wife’s visions, without being their creator.

- Plantard learned from this dynamic: he, too, positioned himself as the one who “reveals” secret traditions, while leaning on others’ scholarship, money, or networks for validation.

Putting it together

- Geneviève Zaepffel → gave Plantard the mythic, prophetic, Celtic/Arthurian worldview.

- René Zaepffel → provided the example of how wealth and social status could amplify esoteric authority.

- Freemasonry → gave him the structure, lineage-building, and secretive hierarchy to formalize it.

Out of this mix, Plantard forged the Priory of Sion myth: a wealth-backed esoteric authority, wrapped in legendary myth, and legitimized by the language of secret societies and hidden lineages.

The main Masonic influences on Plantard seem to cluster in a few key areas:

The Rites of Memphis and Misraïm

- These “Egyptian” rites fascinated Plantard and provided much of the symbolic language (Ormus, Hermetic Egypt, sacred initiations) that later reappeared in the Priory of Sion mythos.

- Though considered irregular or spurious by mainstream Freemasonry, they preserved a rich imaginative tradition linking Egypt, the Templars, and occult Christianity — exactly the blend Plantard recycled.

- Their texts, especially those of J.-É. Marconis de Nègre, contained the lore of Ormus, the Disciples of Memphis, and esoteric cosmology.The files came from the Hautpoul family, central of the affair at Rennes-le-Chateau.

The Philadelphes of Narbonne & the Chefdebien family

- The Marquis de Chefdebien founded this proto-Masonic society in the late 18th century.

- His family had genealogical ties to the Hautpoul line of Rennes-le-Château — the very family Plantard and de Chérisey later roped into the “Saunière parchments.”

- This overlap gave Plantard a ready-made bridge between Masonry and the Rennes legend.

Vichy-Era Confiscated Archives

- Under Marshal Pétain, Freemasonry was outlawed and its archives seized (from 1941 onward).

- These included extensive records of Memphis-Misraïm and other fringe rites.

- According to John Saul, Plantard (possibly via Henry Coston) may have had access to these confiscated archives at the Centre d’Action et de Documentation in Paris.

- This could explain why Plantard had knowledge of obscure Masonic/occult material that seems disproportionate for his age and background.

The Blending of Masonic Lore with Christian Mysticism

- Freemasonry often blends Biblical symbolism with esoteric cosmology.

- Plantard absorbed this, then repurposed it into a Catholic-esoteric synthesis: the Priory of Sion presented itself as both a mystical order and a guardian of a “Christian bloodline.”

- His quote about Canopus as the sublime eye of the architect is pure Masonic-style cosmic allegory — showing how stellar myth was reframed in esoteric terms.

Influence of Esoteric/Occult Masonry on Alpha Galates

- Plantard’s wartime group, Alpha Galates, imitated Masonic-style structures: hierarchical grades, initiations, and lofty titles (e.g., “Druidic Majesty”).

- This suggests that he didn’t just read Masonic material but actively modeled his organizations on its framework.

- The work of Paul LeCour

In short: Plantard was influenced most directly by the Egyptian rites (Memphis-Misraïm), the Narbonne Philadelphes/Chefdebien family link, and wartime access to Masonic archives. These gave him mythic material (Ormus, Egypt, Templars), genealogical connections (Hautpoul–Rennes), and structural models (degrees, grades, orders). He then hybridised this with Catholic-esoteric mysticism to forge the Priory of Sion.